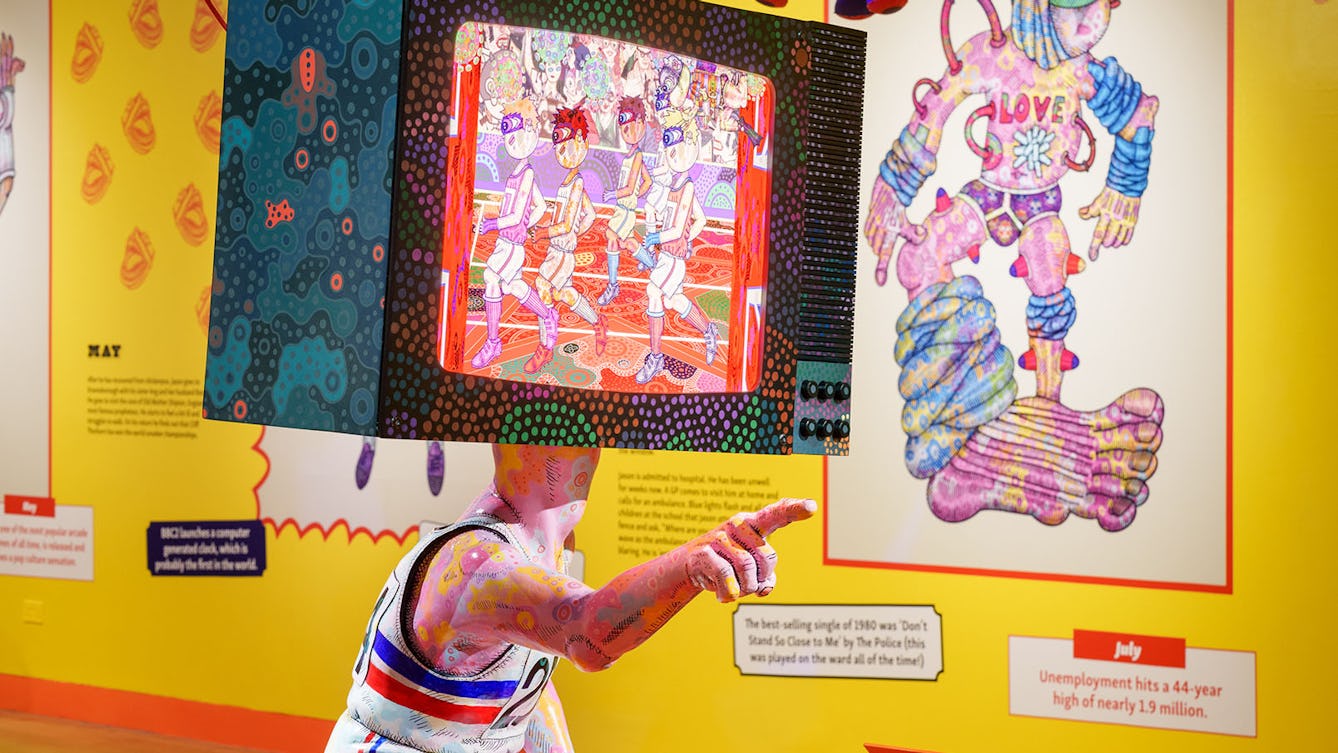

This sculpture depicts the athlete Seb Coe, about to run the men’s 1500-metre race on 1st August 1980 – at the Moscow Olympics.

The life-sized figure is crouched on a vermilion rectangular plinth, about the height of a low step. He wears a sports vest, shorts, long socks and running shoes. The kit is white, with red and blue stripes – which depicts the Great Britain Olympics kit.

Seb Coe is pointing to my bed sculpture, which is directly in front of him, and the figure in the bed is pointing back at him. Virus soldiers occupy the space between them. Seb Coe’s outstretched arm is urging the virus soldiers on to ‘attack’ the figure in the bed.

Seb Coe’s vest, front and back, has his race number of 254 – in large, darkly coloured numbers; this number is very important. His body is highly decorated and painted with psychedelic cellular patterns in flesh pink and other soft colours. He also has sharp defining lines of cross-hatching over the whole surface of the sculpture. These are the lines of shading from the original pen drawings.

I’ve replaced Seb Coe’s head with a large 1970s television set, which back then were big box shapes, not flat like now. Inside the television there’s a diorama of the 1980 Olympic race, frozen in time, and this is how I experienced it myself, via a TV set which was directly in front of my hospital bed. The TV was always on.

The 1st August 1980 is such an important date, as it was when the consultant told my mum and dad that I would be in a wheelchair for life and that I would be lucky to live beyond the age of 16. I remember this dramatic news so well, as it coincided with this huge race, which was the men’s 1500-metre final. There had been a huge media focus on the two favourites, Seb Coe and Steve Ovett. It was on all the newspaper front pages and was the headline of the TV news.

Whilst all that drama was going on around my bed, I watched the race, but overheard the doctor talking to Mum and Dad, who were obviously very upset.

The importance of the shirt number is that it corresponds with the time I was diagnosed. I know this, as visiting times were 2.30 to 3.30pm – which was the same time my consultant was doing his ward rounds. The race started at 2.50pm and I was watching it as the consultant was giving Mum and Dad the news. I was more interested in the race than the life-changing news which was unfolding around me. So the number 254 is an important number to me, as it’s the time when my life changed. But it was the drama off-screen that makes the time, date and shirt number so important.