At the end of her exploration of happiness, Kate Wilkinson talks to two people in their eighth decade of life. One, a keen gardener, has over 300,000 Twitter followers, and the other runs a music festival. But happiness, perhaps inevitably, remains complicated.

Active pensioners, blooming gardens

Words by Kate Wilkinsonartwork by Laurindo Felicianoaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

Gerald Stratford is talking in his slow Cotswolds lilt about his love of root vegetables. “There are so many different types of gardening – I like the excitement of growing anything that grows in the ground and you don’t know what’s there until you dig it up.” It’s the “element of the unknown” that he loves about parsnips, carrots and potatoes.

Gerald has been gardening all his life but only became “heavy into growing big veg”, as his Twitter bio states, in the past four years. I’m speaking with him over the phone, but his face and produce are already familiar to me because, like many thousands of people, I started following his Twitter account during the first UK lockdown in March 2020 after he posted a photo of the potatoes he had grown in a bucket.

During the second UK lockdown in November he posted, “I love apples I have two a day summer and winter cheers,” with a photo of him smiling, holding some shining red and green apples. The post combines the things that define his popularity: an appreciation of simple pleasures, idyllic photos of his garden, and his sign-off, “cheers”, suggesting an amiable warmth and endearing formality rather than the graceless style and cynical tone more typically found on Twitter.

Many of Gerald’s followers are fellow gardeners keen for advice, but there’s a wider audience too. His first viral post received comments like “the best account on here”, “Very wholesome account with old man gardening,” and simply, “Everyone follow Gerald.” More recently, someone tweeted: “twitter has taught me u cannot be 100% happy unless u r an elderly man growing massive root vegetables in pastoral england.”

Gerald’s online success disproves the stereotype of older people being bad with technology, although his occasional slip-ups only add to his authentic image. More than anything, it’s Gerald’s simple hobbies that followers love. He knows something that many struggle with: what to do with his free time.

He now has a book coming out with Headline and has featured in a Gucci campaign that saw him teaching gardening to a bunch of attractive young models in an idyllic English garden. In a cultural reversal, it’s as if young people are now learning how to have fun from retirees like Gerald.

“More recently, someone tweeted: ’twitter has taught me u cannot be 100% happy unless u r an elderly man growing massive root vegetables in pastoral england.’”

Received ideas and ageist assumptions

During 2020 many older people provided inspiration to the locked-down youth, from the late Captain Tom walking around his garden for charity to Bill Bailey winning ‘Strictly Come Dancing’. Bailey, despite being a relatively sprightly 55, is still coded as ‘old’ in the showbiz world of ‘Strictly’.

There’s no denying the genuine achievements of these men, but there seems to be a lower bar for ‘inspiring’ the older someone gets. Someone with grey hair having a good time is somehow surprising: they must have had to struggle to overcome the grimness of getting old.

Maybe older people are more accepting of their own limitations, or have less egocentrism, or have a more mellow attitude.

Each age has its stereotypes, and old age is just the same. In Shakespeare’s ‘As You Like It’, Jaques’ famous ‘Seven Ages of Man’ speech illustrates old age as a time of decline:

Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

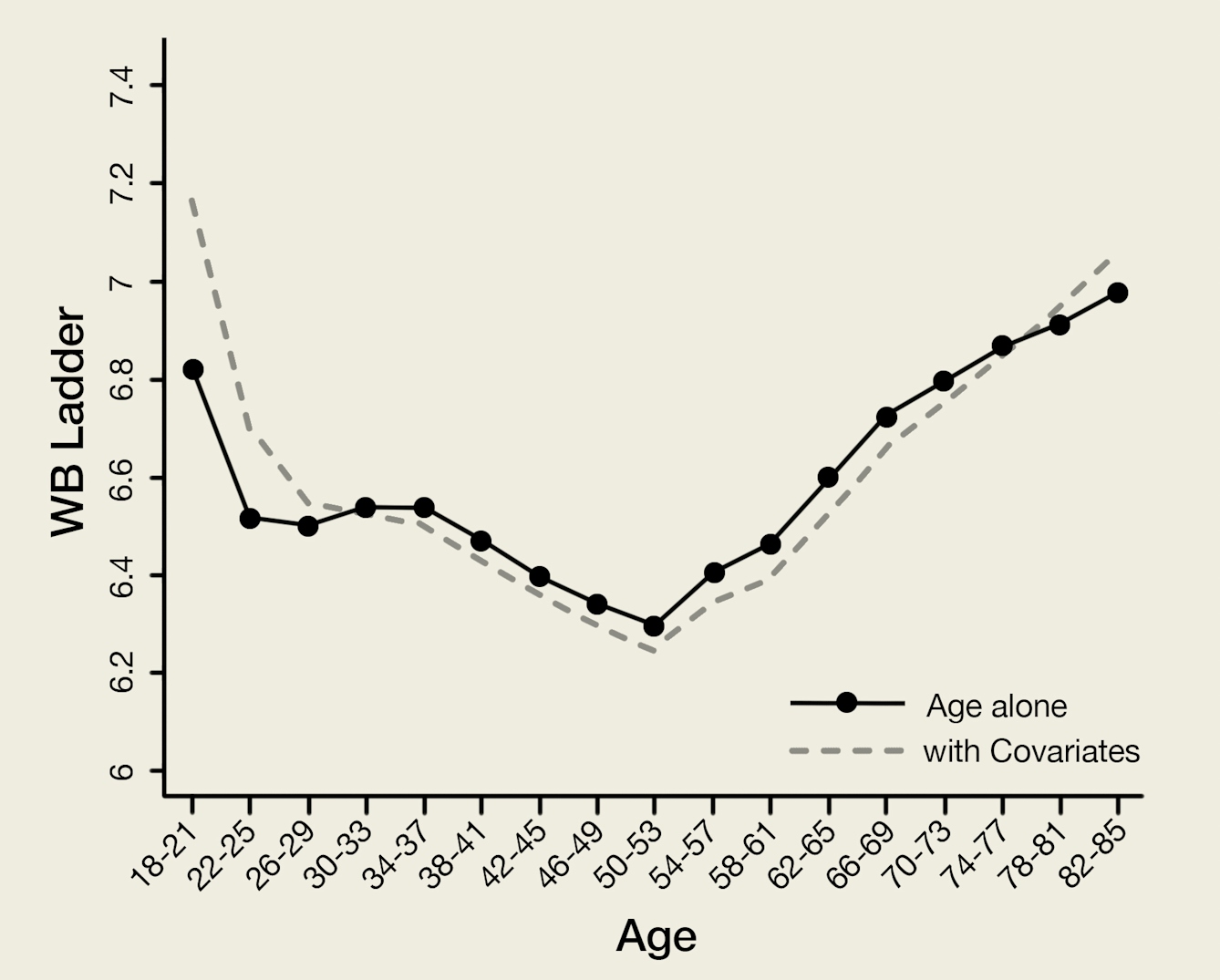

We no longer have quite such a bleak view of old age: many now live a healthier and longer later life. Ageist assumptions have more to do with social significance than health, positioning older people as objects of pity. In fact, research suggests that after the low of the midlife crisis is reached, we experience increased feelings of happiness and contentment as we get older.

It’s not that life is necessarily materially better, it’s a subjective measure based on how people report their own wellbeing throughout their lives. Maybe older people are more accepting of their own limitations, or have less egocentrism, or have a more mellow attitude. The data provides an interesting large-scale view, but it won’t account for individual difference.

Driven to meet challenges

One milestone on the way to old age is retirement. Richard was 50 when he got “slung out” of his stressful London council job, and he’s been occupying his time with voluntary activities for the past 25 years.

He bought a second-hand clarinet in his 40s as a way to have fun with his daughter as they learned together. He now conducts two community music groups, organises a music festival every year, and since retirement he’s also completed a part-time PhD in musical composition. He also pursues long-distance cycling, which he took up after injuries put a stop to his marathon running.

His life now centres around an activity he started at 40. Trying new things doesn’t seem to be a deliberate choice for Richard. “I’ve always been very ambitious and not achieved the things I’ve sought to do,” he says matter-of-factly, “until very recently.” Earlier in life he tried to become a Labour MP and failed, but now admits he “probably would have hated it”.

He’s not quite sure where his drive comes from, as he didn’t have pushy parents. “I was always willing to create things,” he told me. It’s a quality that helps him in his new world of music and academia.

“’My default mental state is rumination about the past,’ says Richard, ‘opportunities not taken. Things that might’ve happened. Roads never travelled down.’”

When lockdown hit, Richard spent the first two weeks cancelling events. “The great majority of what I did and what structured my week was wiped out,” he says. He needed to rely on coping strategies to stave off loneliness. “My current strategy has been to have a plan for each day. I’ll think – who shall I ring this evening? Who shall I go for a walk with next week?”

Even before lockdown, Richard says he could get “quite depressed” about being alone, having been single for some time. When long-distance cycling in Europe, he says, “You can feel very alone at times, sitting in a restaurant in a different place each evening. And you have a nice meal, and you sit and you look at the chair across the table and wish it wasn’t empty.”

He distracts himself from these moments of gloom by focusing on the challenges of the cycling trip: staying on the road, using a different language, navigating accommodation and food.

Over the course of my phone call with Richard, a complicated impression builds in my mind. It doesn’t seem like he’d have much time to sit still, but when he does, he’s often looking backward rather than forward. It’s a quality that he attributes to ageing, since “the bulk of life is behind you”. “My default mental state is rumination about the past,” he says, “opportunities not taken. Things that might’ve happened. Roads never travelled down.”

Despite the brooding, Richard sees many positives about this stage in his life and is grateful for the “great compensation and a pension” he received when he retired. It’s given him financial freedom he’s never had before, and the time to find something that gives him pleasure – his music.

“Despite the brooding, Richard sees many positives about this stage in his life. It’s given him financial freedom and the time to find something that gives him pleasure – his music.”

Family and memories

Gerald’s mentality is less brooding than Richard’s. “When I go to bed I’m thinking of my first job the next day,” he told me. Nevertheless, he too dwells on memories, and thinks frequently about his dad, who died when he was 19 and who inspired his interest in gardening. “Not a day goes by I don’t talk to him about my garden,” Gerald says.

Both mention family as a source of joy. For Richard, his grandchildren are “the most satisfying thing that produces the most genuine happiness”, more so even than his music. They also greatly value their health, having both seen off prostate cancer in the past decade.

Last September Richard fell over and broke his arm. “It suddenly made me feel very fragile,” he told me. He’s gradually planning to reduce the scale of his activities, admitting that he tends to feel pretty tired at the end of every day.

I started writing this serial about happiness through age in February 2020 and the seasons kept time with the loose sequence of the pieces as I wrote, from childhood in spring to old age in winter. As the final chapter came into view, the days were getting shorter, the trees barer, my fingertips colder. Changing weather provides an easy metaphor for ageing; withering plants as withering bodies, snow as white hair, shortening days as time running out.

But it’s important to remember that not all people find winter depressing, not all places in the world even have seasons, and not all people treat old age as if it’s the end. Many, in fact, find multiple other lives within the grey, because they know that there is no end point where we will finally be happy.

About the contributors

Kate Wilkinson

Kate works at Pushkin Press. When not submerged in a book, she can be found walking or practising Spanish. Sometimes both at once.

Laurindo Feliciano

Laurindo Feliciano is a Brazilian contemporary artist and illustrator who has been living and working in France since 2003. Inspired by vintage aesthetics, he creates illustrations using techniques such as collage and digital painting. All his illustrations and posters share a certain nostalgic flair and a great passion for surrealism. His work has been published and exhibited in several countries, and in 2014 he won the AOI (Association of Illustrators) Professional Editorial Award. Among his clients and collaborations are the Musée des Arts Décoratifs/Paris, the V&A, British Airways, WIRED, the Financial Times, Penguin Vintage, Netflix, and many others.