Nearly ten years after Audrey's death, the archive of her work has been made available to the public, and Carol Morley’s film about her has premiered. Elena reflects on letting go of her intense immersion in all things Audrey.

Audrey in the world

Words by Elena Carteraverage reading time 9 minutes

- Serial

The volumes are stacked up on the shelves, in neat, chronological order, and the lights in the basement turn off behind me as I walk out of the library stores. At the time of writing, it’s one week until Audrey’s collection is made available to the public to view. It’s a process that involves simply selecting “harvest = yes” in the database and then the catalogue records will appear on Wellcome Collection’s online catalogue, ready for anyone to request and see.

I feel nervous about it. I’ve been having anxiety dreams; my therapist is getting very used to hearing me talk about Audrey. I have not had a collection get under my skin like this before. But there’s something about Audrey and the works she left behind – and I know I’m not the only person who feels this way about the archive.

I first met director Carol Morley in the library’s Rare Materials Room, as she called me over excitedly to show me a passage she’d just read in one of Audrey’s volumes. Her perfectly painted nails gripped my arm as she gestured enthusiastically and grinned at what she was reading. A researcher caught in the moment of discovering something new is a really beautiful thing to see when you’re supervising the desk.

As Carol packed up to leave the Rare Materials Room, she told me she sometimes would travel home on the bus and would find it hard to snap out of Audrey’s world and back into herself.

Carol Morley started delving into the Audrey Amiss archive in 2015, when she received a Screenwriting Fellowship from Wellcome Trust. Before long, Carol was a frequent visitor in the Rare Materials Room, with a trolley filled high beside her, collapsing under the weight of volumes. Every now and then you’d hear her laugh or gasp in the otherwise quiet room.

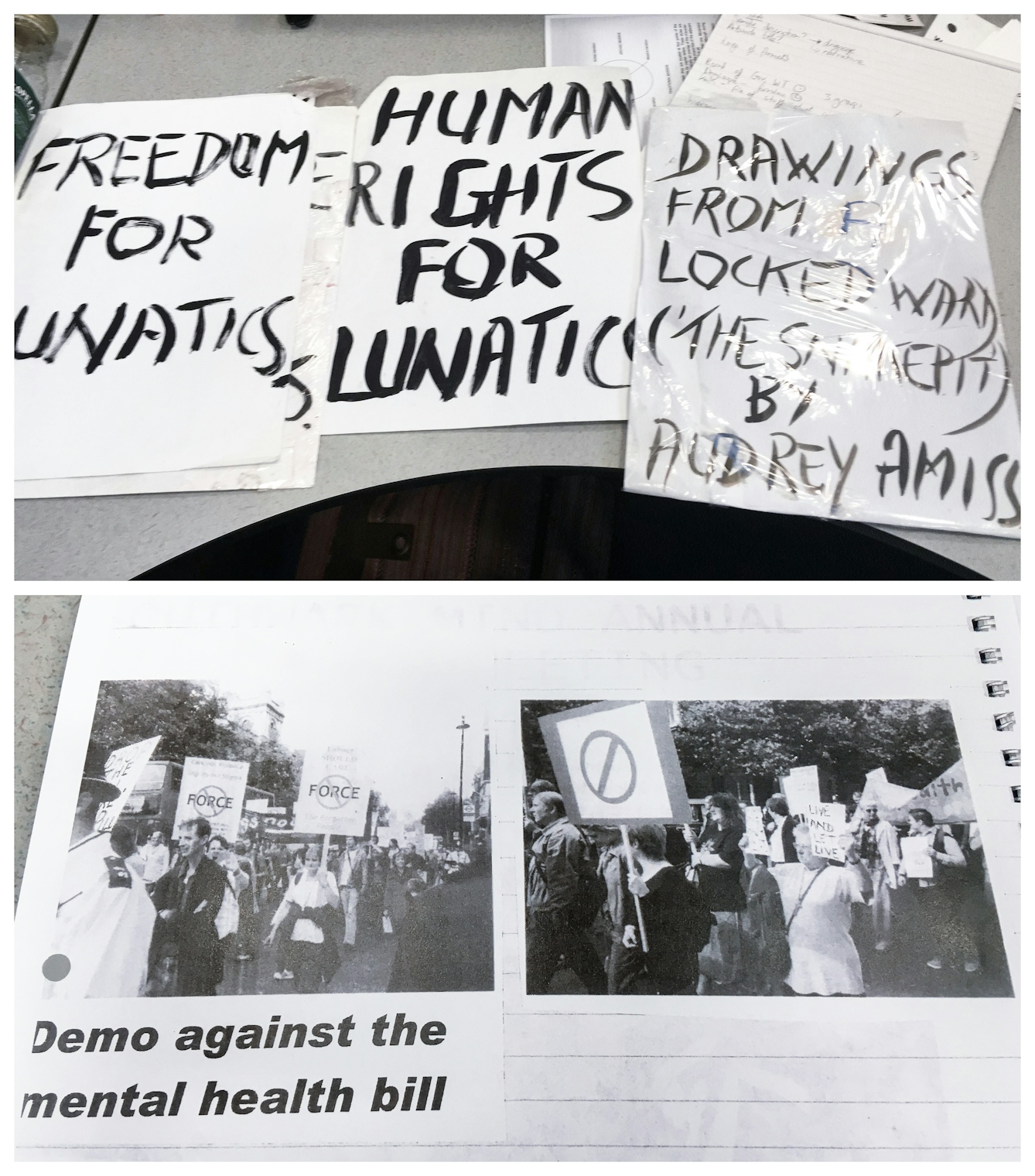

Top: Protest signs made by Audrey for an exhibition ‘Drawings from a Locked Ward (“The Snakepit”)’ PP/AMI/A/25. Bottom: Southwark MIND newsletter from the 2001 demo against the mental health bill, picturing Audrey holding one of her protest signs (right-hand photograph, wearing a white t-shirt). Documentation photographs.

At that moment in time, I was an outpatient at the Maudsley Hospital, a hospital Audrey had spent time inside against her will. I would leave work early, pack the books away into boxes to open the next day, and walk through the main entrance of the Maudsley, thinking of Audrey. As a psychiatrist peered down at me over his notebook and gave me a diagnosis I didn’t agree with, I wanted to shout, “THERE IS NOTHING WRONG WITH ME” – words Audrey often angrily wrote in block capitals in her books. On the bus home, like Carol leaving the library, I was thinking of Audrey.

Working on a collection this personal sometimes meant there were moments of synchronicity like this, where Audrey somehow resonated with my life or made me feel I had a window into another world. I fully accept that my experiences were nowhere near as acute as Audrey’s. But being at the Maudsley, in the same grand, crumbling red brick, just made me think of those who had been there before me. All the people who had nervously entered that building, like me, all the different worlds that they inhabited. All the human experiences that we have no idea about, all the stories that are never recorded in archives.

Bringing Audrey’s story to life

The film Carol was working on became ’Typist Artist Pirate King’, its title what Audrey scrawled in her passport as her occupation. The film is a fictionalised account of a road trip between Audrey (played by Monica Dolan) and her psychiatric nurse (Kelly Macdonald), a journey back up north to Audrey’s home in a last-ditch attempt to gain recognition for her artwork.

Left: PP/AMI/B/85: Sketchbook: central-London traffic, London Zoo, views from Audrey’s living-room window (Dec 1975). Right: PP/AMI/B/97: Sketchbook: London Zoo and autumnal trees (Sep–Nov 1976). Documentation photographs.

The film draws heavily on the archive, with Audrey’s artwork framing how the world is seen, and Audrey’s dialogue and real-life experiences colouring the narrative. It’s deeply informed by all those hours of painstaking research in Wellcome Collection’s library. This blend of fact and fiction feels a very apt way of showing Audrey’s world.

The film, the archive, who Audrey was, all become a merge of colours on a page, like one of Audrey’s abstract paintings.

Audrey’s family were the first to see ‘Typist Artist Pirate King’ at a private viewing at the BFI (British Film Institute) in London – a reflection of the warm relationship Carol has developed with them. When Audrey’s sister, Dorothy, died in 2022, Carol was at the funeral. The film is dedicated to the memory of Dorothy. Dorothy and her husband John met with Gina McKee, who plays Dorothy in the film, joking that he was having dinner with his “two wives”. Fact and fiction blurring. The film, the archive, who Audrey was, all become a merge of colours on a page, like one of Audrey’s abstract paintings.

The heart of the film is an imagined attempt by Audrey to find recognition for her art. This feels fitting: Audrey always wanted to be recognised for her talent as an artist. We can’t know if she wanted her works to end up at Wellcome Collection, where people would read her thoughts and try to understand who she was.

Audrey wrote: “I think that my letters and pictures are the property of the recipient after I have parted with them, supposing the recipients are people of discernment.” To me, people of discernment are people who will respect and listen to Audrey, and I hope that is what we’ve done in how we’ve made the collection available. While we can’t know what she would have wanted after her death, I always come back to her desire for recognition.

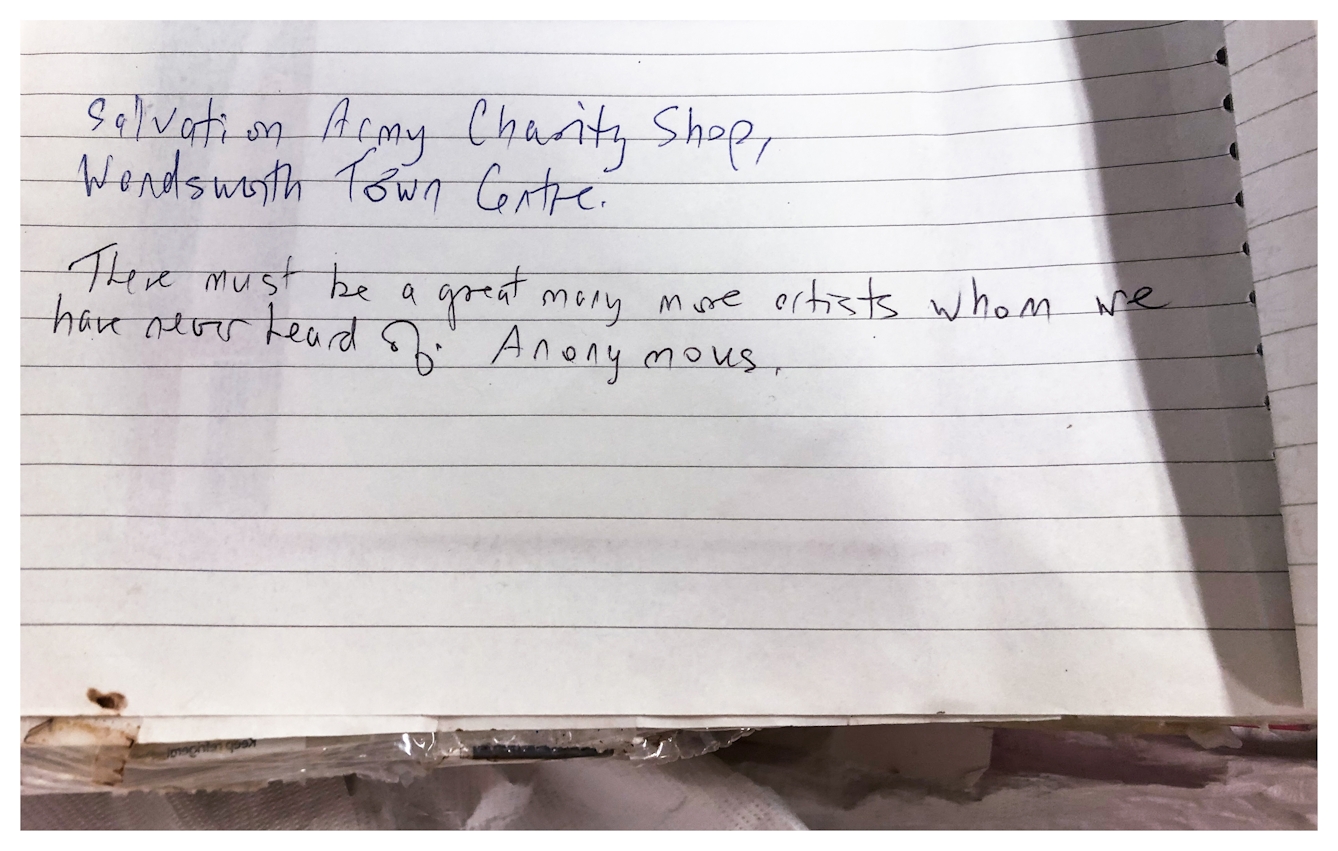

Detail of Audrey's handwritten note from one of her scrapbooks. Documentation photograph.

Audrey now has a Wikipedia page. This wouldn’t have been possible when the archive was first donated; then, there were no published articles about Audrey, no verifiable sources to draw on. For someone to have a Wikipedia page they must pass the notability criteria – there have to be a certain number of reliable sources to draw on to prove the person is ‘notable’. This systemic bias leads to a gender gap, with fewer biographies written about women, partly because there are fewer sources to draw upon to prove their ‘worth’.

Once the archive was acquired, I was consciously thinking about sources that could be drawn from so that Audrey could have her own Wikipedia page. With buzz around the new film, and some pieces written by Carol Morley, along with a few other articles, Audrey Amiss became notable.

Silenced by the mental health system

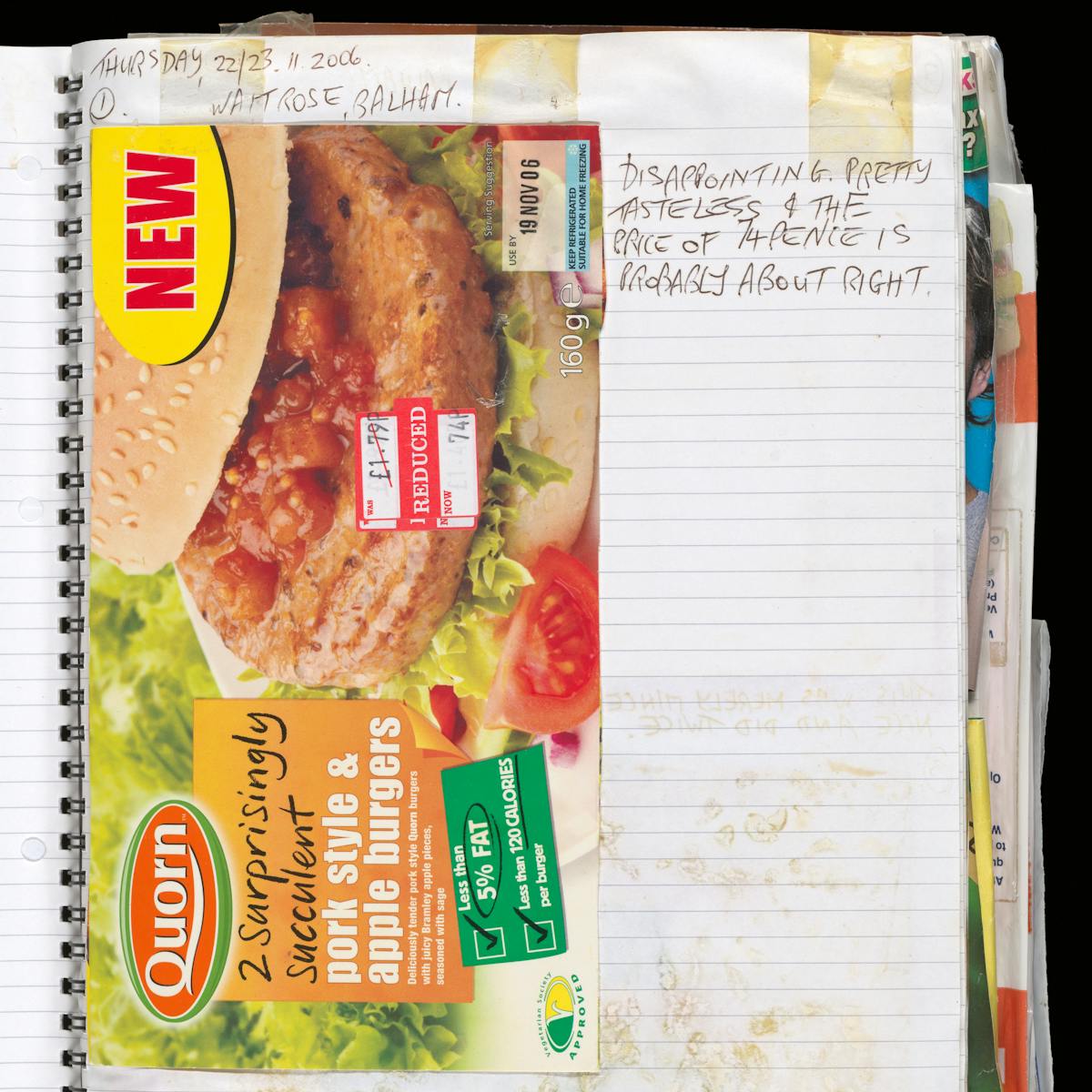

Audrey once wrote that “there must be a great many artists whom we have never heard of” – a reference perhaps to her own unknown status as well as a thought about how many other artists or lives never receive the acclaim they deserve. Audrey’s is a life that we could easily have never heard of too, had the archive not been saved after her death.

And it wasn’t just in her art that Audrey felt ignored. As a patient, she received heavy-handed treatment in psychiatric care as a revolving-door inmate on locked wards, enduring forced medication, and sometimes, in earlier years, electric-shock treatment. She wrote angrily, telling anyone who might listen, how she was treated by psychiatrists, positioning herself as both a mental health survivor and activist.

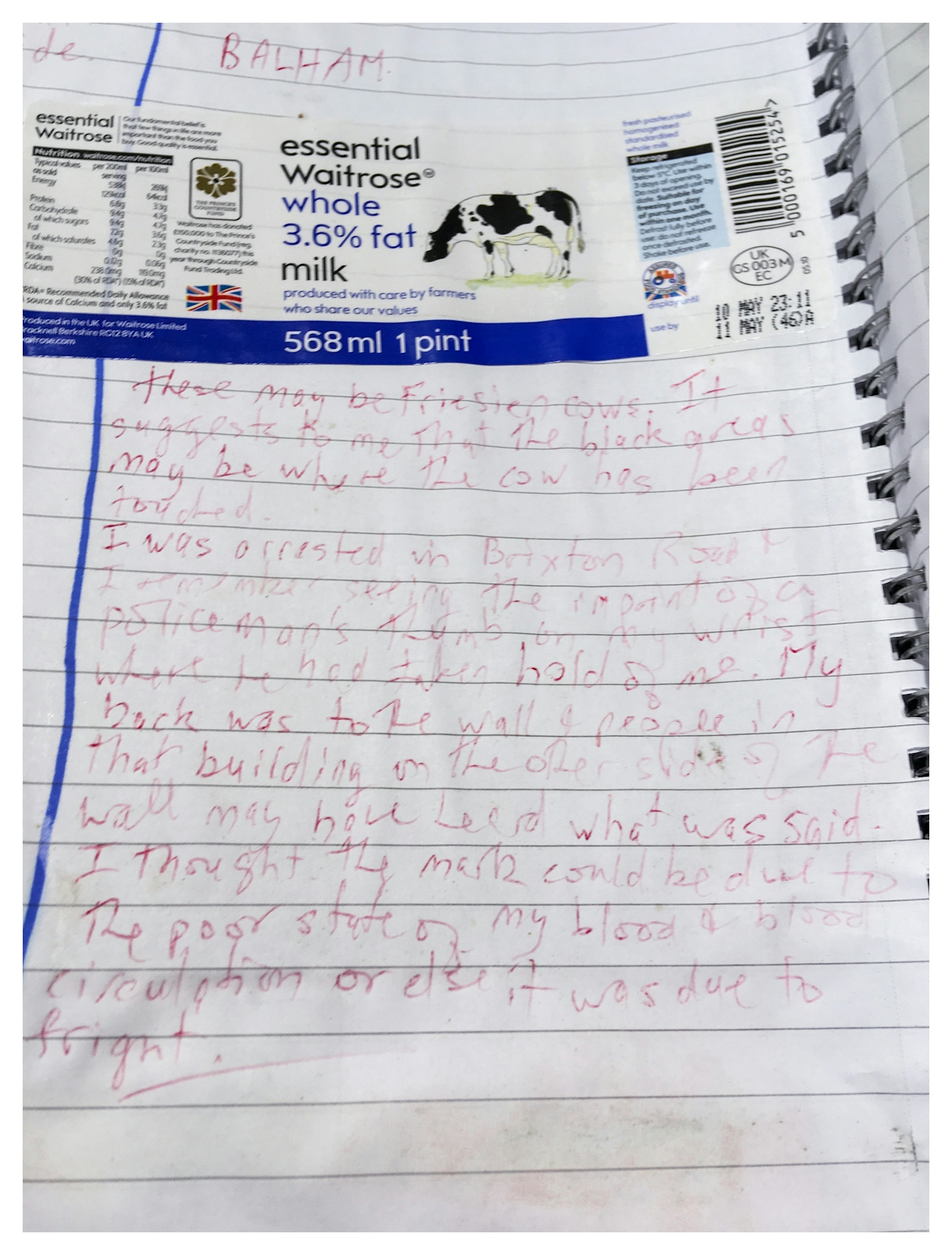

Detail of milk-bottle label and Audrey’s handwritten note from one of her scrapbooks. Documentation photograph.

What happened to Audrey was often against her will and nobody was listening to her. “There’s nothing wrong with me,” she said, and I think of how many others have had their voices silenced within the mental health system.

What happened to Audrey was often against her will and nobody was listening to her. “There’s nothing wrong with me,” she said.

Through Audrey’s experiences, the archive holds up a mirror up to others living on the margins of life, who are shunned for experiencing the world in a different way, whose ‘madness’ makes them unpalatable. In one of her scrapbooks, next to a glued-down milk carton picturing a dairy cow, Audrey writes: “the black areas may have been where the cow was touched. I was arrested on Brixton Road and I remember seeing the imprint of a policeman’s thumb on my wrist where he had taken hold of me. My back was to the wall.”

The casualness with which Audrey describes this violence, of being arrested and manhandled, is a stark and uncomfortable reminder of how institutional violence intersects with severe mental illness. A milk carton, a black-and-white cow, and a bruise from a policeman. And yet Audrey’s is not an isolated case, and these stories belong to others besides Audrey, others who have faced similar treatment at the hands of the state. These were Audrey’s people, a community she described as her “fellow lunatics”, demanding to be listened to.

Audrey’s collection in its new home. Documentation photographs.

It’s where the archive is not past but present; today our mental health services are threadbare and chronically underfunded, and fights continue around police intervention and the powers of institutions in managing so-called “high-intensity users” of mental health services. But too often we don’t hear the voices of those who are directly impacted; we don’t hear about people who see a milk carton and think of being forcibly restrained by a policeman.

The archive is unapologetically in the first person – it is Audrey. But it is also a radical recentring of entire forgotten communities, and a catalyst to understanding mental health through a new lens.

Audrey achieves recognition

The pages of the archive go blank after 10 July 2013, the day when Audrey dies. In those blank pages there is an invitation to an archival afterlife where the story continues. While I wish Audrey could have been around to see it, she has now gained that recognition as an artist she desperately wanted. Audrey now has a film about her life. She has a Wikipedia page. Her artwork has been sold at auction. Her collection at Wellcome will be preserved for ever, for anyone to see.

I feel protective of Audrey, apprehensive about how others will engage with the collection, worried that people won’t get it. I’m finding it hard to accept that I’ve done my bit and that it’s now time to hand it over. It’s time to let go and let Audrey out in the world. Harvest = yes. World, meet Audrey.

You can explore the Audrey Amiss archive through our online catalogue. To see the archive, you need join our library and request to view specific items from the collection.

About the author

Elena Carter

Elena Carter focuses on developing the collections at Wellcome to challenge the way that we think and feel about health. Elena is particularly interested in radical and social histories and material that gives voice to marginalised groups. As Collections Development Archivist, she works directly with people to find the best home for their materials, with a focus on working collaboratively and ethically.