For a long time, nobody talked about menopause, and although things are changing, information and support can be hard to find. In the first of a series of articles, we’ll hear the voices of contemporary women talking about their periods during menopause, and oral historian Helen Foster will explore the history, myths and taboos around blood and menopause.

Blood

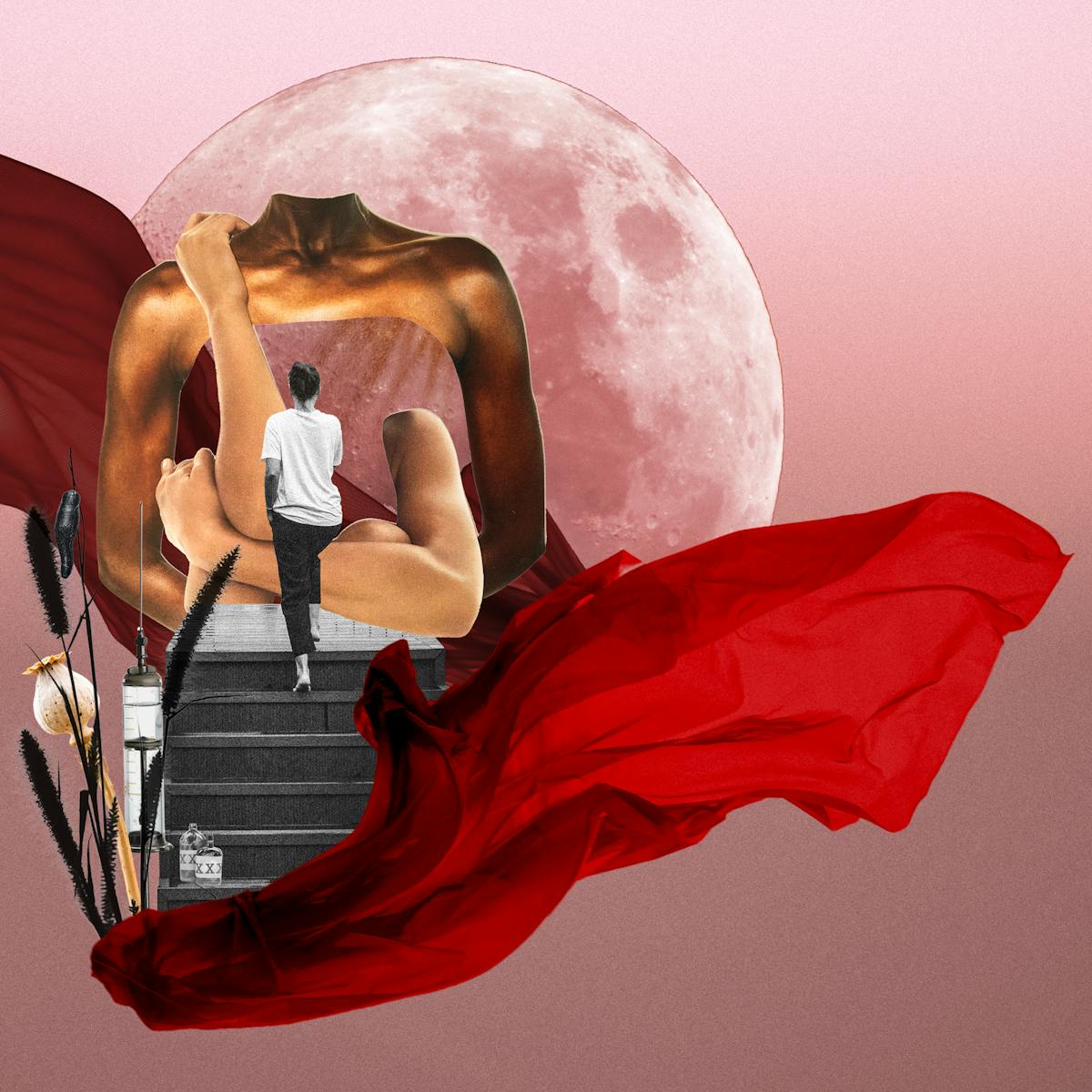

Words by Helen FosterEast Midlands Oral History Archiveartwork by Asma Istwaniaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Article

- Serial

Although we talk about menopause more now than we used to, it remains a subject shrouded in mystery and taboo. Here are some of the facts. A person is said to have reached menopause when their periods have stopped for at least 12 months. It is caused by dropping levels of the hormone oestrogen in the female body.

The average age of menopause in the UK is between 50 and 51 years. Early menopause, which happens before the age of 45, is experienced by about three per cent of females in the UK, and about one per cent will experience a premature menopause before the age of 40. Menopause can also be induced surgically by interventions such as hysterectomy, when the womb is removed.

A wide range of symptoms can occur in the years leading up to menopause, a phase called perimenopause. These include hot flushes, mood swings, brain fog, vaginal dryness and erratic periods.

Menopause and blood

Sophie is one of a group of menopausal people who participated in ‘The Silent Archive: Spoken Testimonies of Menopause‘, an oral-history project in the East Midlands. Blood was a major part of her experience of menopause.

For most, menopause is not an abrupt cessation of menstrual bleeding. During the months and years of perimenopause, a person may experience shifting and irregular patterns of bleeding, and changes in the nature of the blood and discharges from the vagina. Periods that suddenly go on for weeks can be alarming, especially when, as Rachel says: “No one specifically measures how much blood or talks about how much blood you lose…”

“During the months and years of perimenopause, a person may experience shifting and irregular patterns of bleeding, and changes in the nature of the blood and discharges from the vagina.”

Menstrual myths

Although in recent years conversations about menopause have become more mainstream, the intimate workings of the female body can still elicit sneers, sniggers and uneasy silences. The taboos around menstruation and menopause have their roots in history and folklore.

Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), recorded in his ‘Naturalis Historia’ that menstruating women could turn wine to vinegar, kill bees, make crops wither and dim mirrors.

Menstrual blood was thought to be dirty, corrosive and toxic, with the ability to damage the male penis. Expelling blood from the body through menstruation was believed to be a natural way for women to cleanse these toxins from the body. It was considered a form of ‘purgation’, which prevented women from being consumed by their inherent sin and corruption.

In his book ‘The Womans Doctour’, the 17th-century physician Nicolaas Fonteyn warned that if women did not menstruate, “the feculent and corrupt blood might… turn to rank poison… in the body and putrify”. It’s not hard to understand, then, why older women who no longer had their monthly bleeds after menopause were viewed with suspicion in times past.

Menopause and medicine

The term ‘menopause’ was coined in 1821 by French physician Charles-Pierre-Louis de Gardanne. In the 19th century, (male) doctors believed that heavy and irregular bleeding, known as flooding – a common menopausal symptom – was necessary to make sure that women would avoid an accumulation of blood in the brain, which doctors believed could lead to physical and emotional disturbances.

“The taboos around menstruation and menopause have their roots in history and folklore. Menstrual blood was thought to be dirty, corrosive and toxic, with the ability to damage the male penis.”

English physician Edward Tilt (1815–93) advised against “nervous excitement” in his older patients for fear that it would attract blood to the brain. Tilt’s treatments for his female patients experiencing what we now recognise as menopausal symptoms were brutal by today’s standards. He advocated “bleeding by cupping” or “leeching”, and stipulated a plain diet with minimal alcohol, regular bowel movements and weekly bathing regimes. He prescribed opium, morphine, carbonated soda, belladonna (deadly nightshade) plasters for the stomach and, probably most barbaric of all, lead-acetate (also highly toxic) injections into the vagina.

In the 20th century, menopause was remodelled as a hormone-deficiency condition, as endocrinology research linked it to a decline in the hormone oestrogen. The changing balance of hormones in the body was recognised as the cause of many menopausal symptoms, and in the 1930s, oestrogen began to be used to treat symptoms such as flushes in early forms of hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Hormone therapy began to flourish, until a study in 2002 opened up debates about the benefits and risks of HRT, and these still continue.

Like many women, Ranjan didn't realise that she was entering menopause and struggled with changes in her menstrual cycle for a long time. When she finally went to her doctor, the response was not helpful.

Today the primary aim of medical intervention is to alleviate the discomfort and disruption of flooding and other menopausal symptoms. But people living with menopause continue to report challenging encounters with the medical profession due to a lack of training and awareness around the subject.

Freedom from periods

Some women mourn the ending of periods as the end of an important phase in their lives, as well as a change in their bodies. But for some, reaching menopause is a time of liberation. The monthly ritual of menstruation that defined their lives is over and there is a sense of freedom. We’ll give the last words to Claire.

About the contributors

Helen Foster

Dr Helen Foster is a writer and oral historian currently based at the East Midlands Oral History Archive at the University of Leicester. She has a particular interest in narratives around life stages and, as well as menopause, her work has explored childlessness and bereavement. As a poetry-therapy practitioner she facilitates workshops for people living with mental health challenges, using writing as a therapeutic tool. She is currently co-authoring a book on creative writing and health for Emerald Press.

East Midlands Oral History Archive

The audio extracts used in the series ‘A Bloody History of Menopause’ come from interviews, conversations and audio diaries about lived experiences of menopause recorded for the Silent Archive project. The project was led by the East Midlands Oral History Archive at the University of Leicester (from 2020–22) and funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Asma Istwani

Asma is an artist and arts producer from London. She has worked with several organisations and brands, including Tate, Somerset House and Jo Malone London on a variety of creative projects. Through her collages she aims to make relatable statements about the experience and racial and sexual depiction of ‘othered’ women, with special interest in those who, like herself, make up the SWANA (South West Asian/ North African) diaspora. Asma is also the founder of RIOT SOUP, an art collective and community for Black and Brown women artists in London.