Melanie Grant and Ana Botella talk about the “all-hands-on-deck thinking” that has allowed creative and sensitive programming and collecting to continue at Wellcome Collection during the Covid-19 era.

The past year has been a whirlwind inside Wellcome Collection. Just one example is the press attention specifically on acquisitions related to Covid. “There’s never been this kind of focus on what we’re collecting,” says Collections Development Manager Melanie Grant. Whereas in the past, “We’ve been very much quietly working away doing our thing… it’s been very, very tense this year; I’ve never seen anything like it before.”

Ana Botella, Acting Head of Public Programmes, didn’t have much of a base of comparison. She’d been in the position for six months before lockdown started: “My colleagues describe it as a maternity cover on acid.” Botella was responsible for all of the museum’s public-facing programmes, including live events, publications and exhibitions.

In the Covid era, the programming wasn’t a case of business as usual. “We’ve had to completely rethink the programme, and to use this as an opportunity to stretch our institutional processes,” Botella explains. Staff had been preparing a programme themed around happiness, which suddenly felt out of sync with the times.

Time frames had to be compressed. Normally a programme would be developed over the course of two to three years, but Covid brought more urgency. In the early days of the pandemic, the team decided to postpone the happiness season by a year. This left a gap of six months to fill. “It’s been a really exciting experiment in rapid-response programming,” Botella notes.

Collaboration in the Covid era

Part of what was lost in terms of time was made up in greater collaboration. The museum’s 30-plus content producers developed ideas together during remote working. But the collaborative model didn’t mean that decision-making was slow. “We committed to really being able to make decisions quickly,” Botella says.

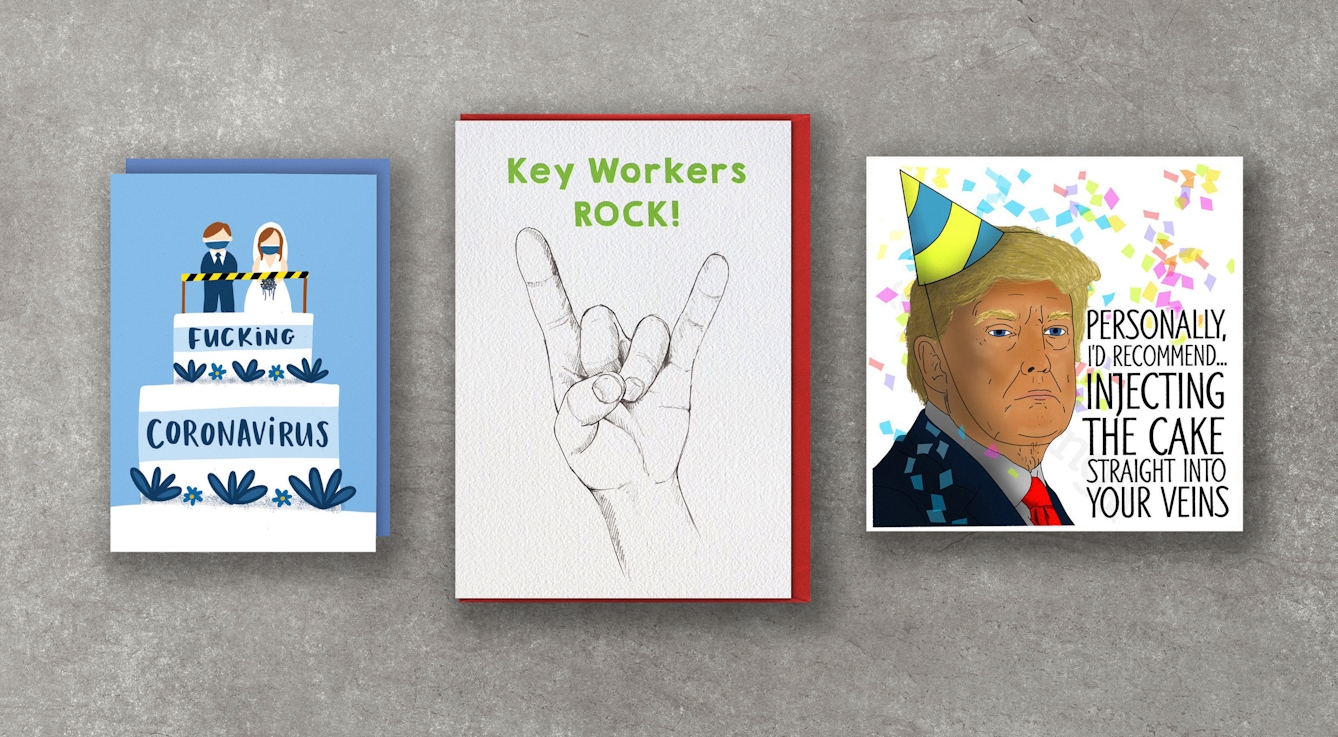

Collecting greetings cards has been a great way to track humour throughout the course of the pandemic.

There was intense collaboration both within the museum, and between Wellcome Collection and other organisations. “Part of the reason for that was we could have ended up with 100 collections with a bunch of face masks in them, and then maybe nothing else,” Grant says laughingly.

“But we wanted to make sure that we found our unique place within other collections, and that we weren’t duplicating what everyone was doing.” This collaboration was mostly informal, starting with other museums in London and spreading internationally via lots of Slack conversations.

We could have ended up with 100 collections with a bunch of face masks in them, and then maybe nothing else.

“It was also important to us at the beginning to state that we wanted to remain within our area of expertise,” Grant reflects, while respecting both the emotionally sensitive nature of people’s lived experiences and the time-sensitive nature of the pandemic’s stages. Rather than collecting, for instance, stay-at-home signs from press briefings, Wellcome Collection liaised with the Science Museum and realised that those materials would have a more fitting home there.

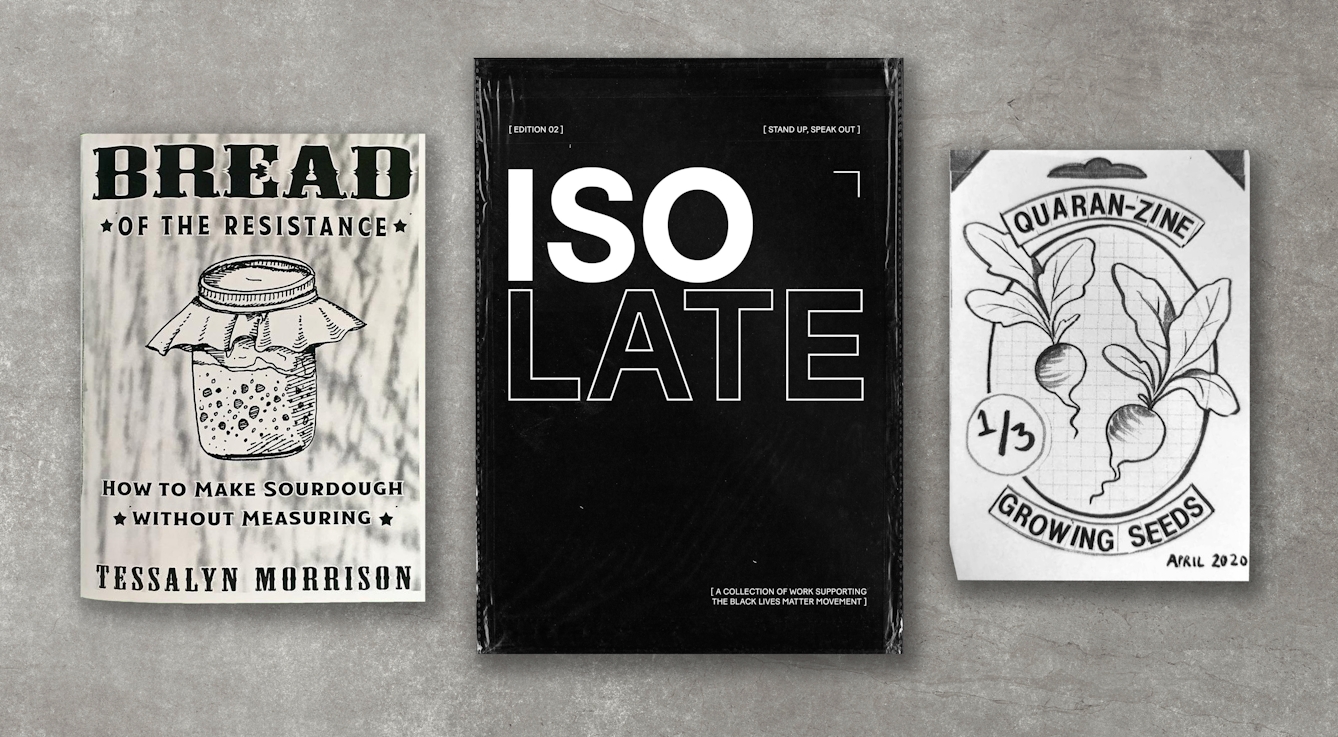

In the short term, the team acquired more ephemeral items like anti-vaxx leaflets and zines providing advice on self-care, such as ‘an empathetic sketchbook zine’. Greetings cards, like ‘Lockdown hair be like’, were another example.

Grant explains, “We’ve been kind of tracking the humour through greetings cards. It’s interesting that at the beginning, it was very much about toilet paper. And then it was about doing yoga at home. And there’s a kind of a trend that goes through different things that people are doing to kind of survive at that time, coming through in a very humorous way.”

Collecting ephemeral items like zines has been a powerful way to preserve people’s lived experiences and represent individual voices.

Overall, aiming to be more thoughtful and less reactive allowed the team to reflect not just on Wellcome Collection’s unique position as a museum and library devoted to health and human experience, but also how to document the moment in a representative way.

For example, Grant relates, “Another principle that we had was really thinking quite deeply about how these kinds of health emergencies really disproportionately impact on certain lives and certain communities. And we saw that very quickly with Covid; it really highlighted social inequalities.”

One response was to commission the artist known as the vacuum cleaner to create short films about staff at Newham Hospital, in a very diverse borough that had one of the highest Covid death rates in the UK.

This principle of taking a step back and being thoughtful about which gaps to fill also applied to reconsidering events. Emily Wiles, a senior live programme producer, says, “We were thinking quite carefully about all of the things that that people are really tired of at the moment, and how people are feeling. So I think the relentless pace of a lot of content online is one thing that we wanted to really avoid.”

Wiles feels that the remote experience the team curated that is the most enjoyable for an audience is the ‘For All I Care’ podcast, a collaboration with the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, and produced by the company Reduced Listening. Listeners can experience these conversations at a slower pace.

‘For All I Care’ collaborative podcast with the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, hosted by Nwando Ebizie.

Finding the connecting thread

Ultimately, the all-hands-on-deck thinking coalesced around the theme “What does it mean to be human, now?” This built on the museum’s permanent ‘Being Human’ gallery, which had opened in September 2019. The expansion of the ‘human’ theme helped to ensure that the permanent galleries continued to evolve in response to waves of change: the pandemic, of course, but also Black Lives Matter, Brexit, and the US presidential elections.

“And this is where the notion of care became central to the programme: care as an organising principle across all spheres of life,” says Botella. “The programme talks about how we care for ourselves and for one another, as well as about public health, environmental health, and the care for our collections.”

For example, artist Rhiannon Armstrong’s project ‘How to Hold, Behold, and be Held’ drew on occult objects from Wellcome Collection to explore comfort and togetherness.

And, of course, the theme of healing is core to the ‘For All I Care’ podcast. Live programme producer Wiles had previously worked on a Friday Late event with the podcast’s host, multidisciplinary artist Nwando Ebizie, and knew that Ebizie would be able to cultivate a sense of welcome and intimacy in the audio space.

Even though the six-month interim programme is firmly rooted in contemporary events, Botella isn’t worried about it becoming instantly out of date. “These issues are not just about 2020, or 2021, and ultimately the programme is about capturing the experience of the present to shape change and project into the future.”

These issues are broad not just in their geographical and temporal scope, but also in terms of their content. As Botella puts it, “We are looking at health intersectionally, rather than following the biomedical model. Our lens recognises that health is shaped by overlapping and interdependent factors such as gender, race, ability, class, age, sexual orientation, or ethnicity.”

Temporary display at Wellcome Collection exploring eleven people’s experiences of “What does it mean to be human, now?”

New understandings of space and success

Naturally, the collection’s Covid response has also had to re-navigate different types of space. The museum has opened and shut several times throughout the various UK lockdowns, and early on the staff realised they needed to be able to engage with both their local community and globally, through digital content.

In terms of the neighbourhood, the museum collaborated with the local charity Copenhagen Youth Project. Disadvantaged young people worked with local artists to create a spoken word project around the theme “What does it mean to be human, now?”

To reach a global audience, a number of events and artists’ commissions had to be brought online. Some of these were straightforward, like an online conversation between nurse and novelist Christie Watson and novelist Elif Shafak, who wrote the book ‘How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division’ during the first lockdown. Other events were more challenging to digitise, such as Rhiannon Armstrong’s artworks, which were released on Instagram.

Describing her perspective on “human now”, Botella reflects, “For me it is about interconnectedness. I think this is what has completely come across. The pandemic is this kind of enhanced visualisation of our networked world, its vulnerabilities and also its strengths. And now it is about seizing the opportunity to harness that interconnectedness to create a future that is better for everyone.”

About the author

Christine Ro

Christine Ro is a journalist whose work is collected at www.christinero.com.