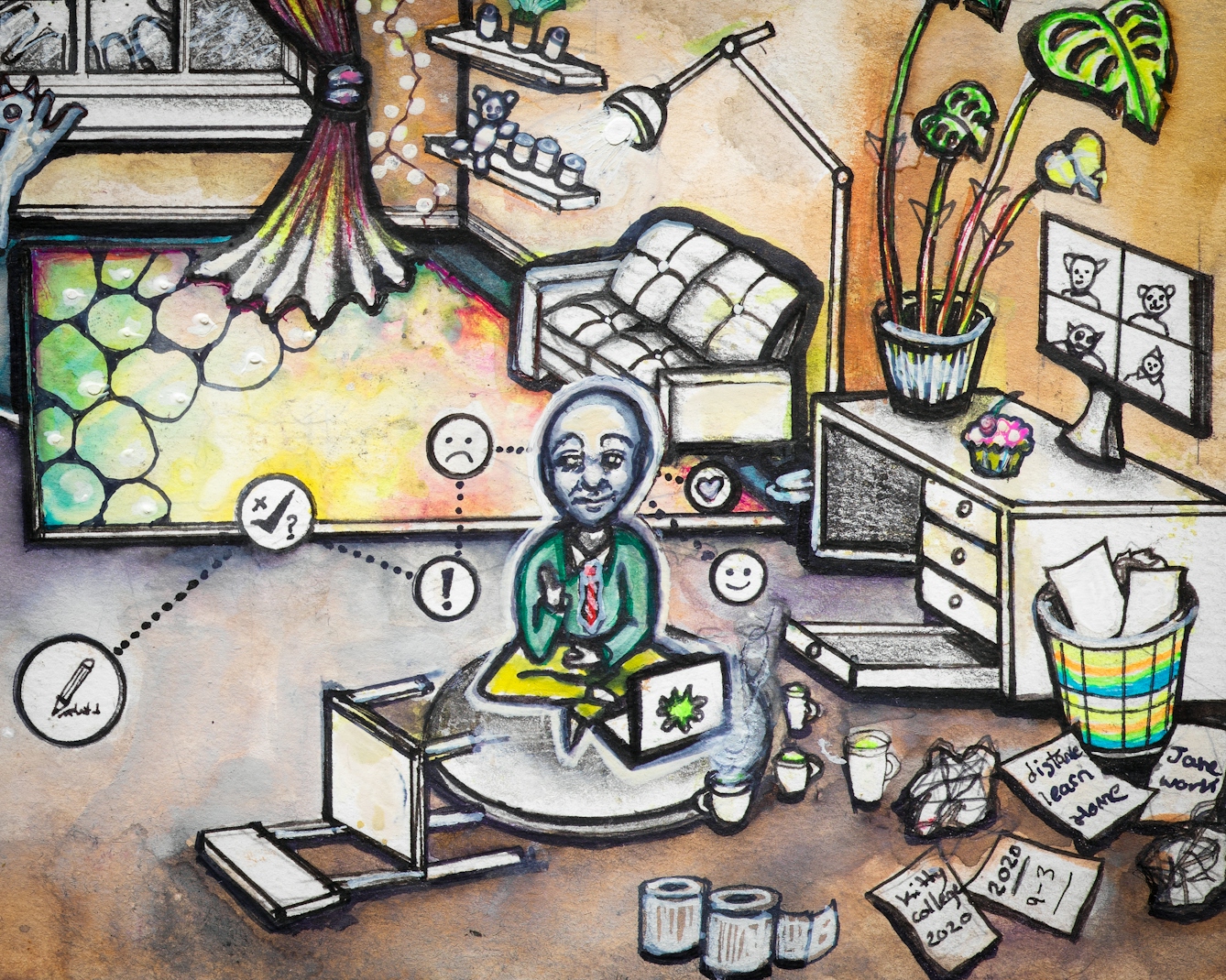

Accepting outside help is unthinkable when it could put your child at risk. Jane Holmes shares how she and her husband cared for their Disabled daughter during lockdown, fitting their work around her needs while trying to ensure that none of them got ill.

Caring for our Disabled daughter in lockdown

Words by Jane Holmesartwork by Carrie Ravenscroftaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

On Thursday 5 March 2020 I drove my daughter Kitty to her residential college for a morning meeting with her speech and language therapist. Kitty is a student at a specialist college for Disabled young people called Treloar. She has severe athetoid cerebral palsy, which affects her brain stem and therefore every single one of her movements.

That day our meeting mostly centred around the risk that Covid-19 would have on a person who was non-verbal and needed hand-on-hand facilitation for all her communication. Due to her cerebral palsy, Kitty finds it impossible to control her intentional movements. The quickest way she has of communicating is to point to words on an alphabet chart, but she needs a facilitator to help her hold her arm still, as her muscles all pull against each other and she finds it impossible to point precisely.

Kitty is so Disabled that she cannot eat, use her hands properly, stand unaided, talk or walk, but she is one of life’s great gifts. A real live wire, she is inquisitive, clever, very opinionated and grabs hold of life with both hands, with a huge smile and a spine of determined steel. She doesn’t actually have a spine of steel yet, though plenty of Disabled young people do, nor is she, in fact, able to grab anything with both hands, but you get the picture.

Home care during a pandemic

Listening to various news reports about the spread of the Covid-19 virus, I drove home after leaving Kitty at the college, feeling distinctly uneasy. I was remembering Christmas 2007, which was spent in the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford with Kitty on a ventilator. It is not a horror I wish to see again as long as I live.

Within five minutes of getting home, I had a phone call telling me that Kitty had had a prolonged seizure shortly after I had left. It’s very difficult to recognise patterns with epilepsy, but even so, her seizures had become more unpredictable than ever, happening at strange times of day and not responding to a recent increase in medication.

I got straight back in the car and collected her from college, resolving to let her recover with us at home for as long as she needed. Fortunately we are a two-parent, single-child family, so I was able to fully focus on her and getting her well, easily able to push my work to one side for a few days.

“Kitty is a real live wire – she is inquisitive, clever, very opinionated and grabs hold of life with both hands, with a huge smile and a spine of determined steel.”

My husband, Jasper, is a teacher at a local special school. The nature of his work makes it impossible to keep any distance at all from his students. With our daughter at home from school after her seizure, he was particularly careful during the following week, showering as soon as he came through the door, following the government guidelines about hand washing and keeping as much distance as is possible when caring for a Disabled teenager who is highly dependent.

Accommodating home care in lockdown

While that week was stressful, the media coverage of the spread of the virus was really disturbing. Horrifying reports were coming through and most people were getting really scared.

The immediate concern was Jasper catching coronavirus and passing it on to Kitty, but we felt that sending her back to college posed an enormous risk. Knowledge of the virus was still scant, and we felt very unwilling to let Kitty out of our sight, worried sick about her catching it. We decided to keep her home. A few days later there was a suspected case at my husband’s school. To our great relief the school closed and he was to teach from home for the foreseeable future. Full lockdown was put in place a few days later.

Caring for our daughter is one of the most fulfilling yet exhausting aspects of our lives. She is without doubt the light of our lives, engaging and fun to be with, but she is also entirely dependent on carers for all aspects of her daily life. At 18 years of age and of average size, caring for her is very physically demanding. At college she has two-to-one care, meaning that she has two carers managing her needs 24 hours a day.

Accommodating work in lockdown

I run a community centre for Disabled children, work which has always fitted round our family life quite easily. However, like most charities, we suddenly faced an uncertain future. Charities are rightly discouraged from stockpiling funds, so it wasn’t long before we got into trouble.

While very many families with Disabled children seriously struggled during lockdown with nowhere to go, we were not able to open our centre at all. We kept in touch with families online, but not being able to offer them our service when some of them were under such pressure without it was very difficult to bear.

“Jasper really took to teaching his class online. He started at around 09.00 and finished in the late afternoon. During that time I was our daughter’s sole carer.”

Jasper really took to teaching his class online. He started at around 09.00 and finished in the late afternoon. During that time I was our daughter’s sole carer. As wonderful as it was to spend so much time with her, there was not any opportunity to tackle my own work during Jasper’s teaching day, so it was mostly done in the early evenings, whenever I could fit it in. Having an early start, Jasper went to bed before us, but I would necessarily stay up with Kitty until she went to sleep, sometimes not until the early hours of the morning.

We tended to share the getting up in the night for her, usually around five times, mostly to reposition her, give her a drink of water, adjust her bedclothes, sometimes to change them altogether, to comfort her in the event of a bad dream or to fly downstairs in seconds if there were any signs she might be having a seizure. This is something we are used to, but it meant that there was very little time or energy for me to get on with my own work.

Emerging from lockdown

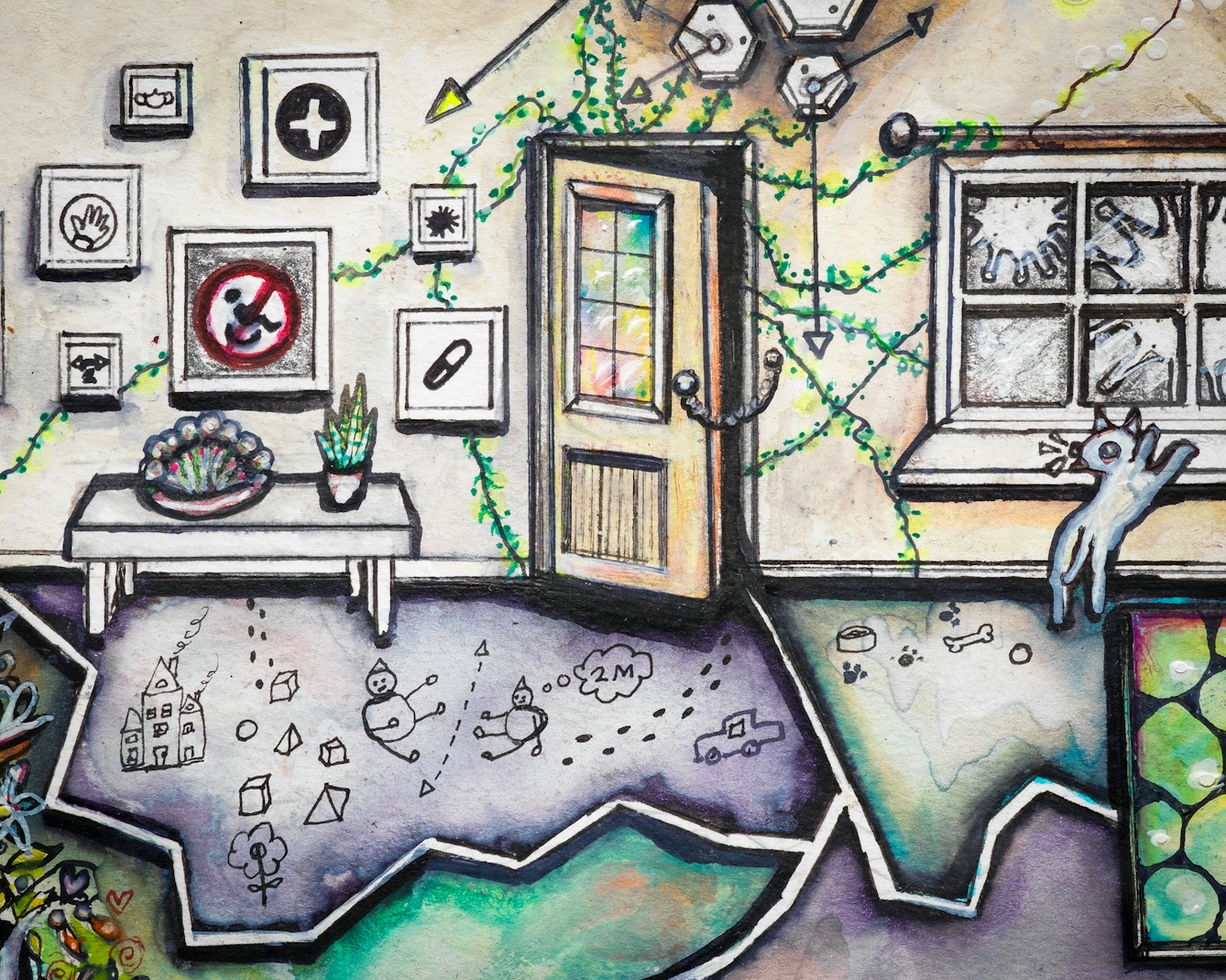

Outside help was not something we would have considered, even if it had been available. We had a weekly email from Kitty’s social worker, but bringing any kind of risk into our home at that time was unthinkable. Our absolute priority was Kitty’s health, and as her only carers, our own health was pretty important too.

It constantly surprised me how fast lockdown passed. We were able to establish a nice routine and with lots of fresh air, sun, rest and very little day-to-day stress, Kitty became really healthy and there have been no more seizures. Despite me shouting at anyone who got too close, we enjoyed some country walks, were lucky enough to get a weekly food delivery and our squabbles were balanced by bonding. But inevitably, the prospect of both my husband and our daughter going back to school and college loomed large.

“I have lost count of the number of times I have heard people reassure themselves that Covid-19 mostly affects people with underlying health conditions, disabilities or the elderly, as though these people don’t matter.”

In September 2020, they both returned to school and I was incredibly worried. Kitty’s college is an environment where people are exceptionally diligent about every aspect of her safety. However, it is still deeply worrying, and although she was champing at the bit to get back to her friends, the instinct was to keep her close. However, with Jasper also returning to work, it is very doubtful that she would, in fact, be safer at home.

The government has been rightly focusing on help for nursing homes, but there has been no extra support for all the extremely vulnerable children and young people with disabilities in special schools.

Left sidelined, ignored and alone

I have lost count of the number of times I have heard people reassure themselves with the thought that Covid-19 mostly affects people with underlying health conditions, disabilities or the elderly, as though these people don’t matter. Similar platitudes have been issued by government representatives themselves. We feel sidelined, ignored and alone, as do thousands of others. And this adds a completely new dimension to the worry and fear experienced by our family.

So many times I have heard the shockingly resentful phrase “why should Disabled people be treated differently?”, as if they are revelling in any extra concessions made, putting two fingers up at the able-bodied, who have to “go without” using a blue badge, for example. A deeper level of kindness, which Disabled people and their carers can reasonably expect, really would make life better for everyone.

The more recent, second lockdown hasn’t made much difference to our family in a practical sense. Jasper is still going to work; Kitty is still going to college. The measures being taken in both of their schools are reassuring, but the risk of them catching coronavirus is substantial. It feels like we are playing Russian roulette on a daily basis, which will only end when a vaccine is approved. I can’t wait.

About the contributors

Jane Holmes

Jane Holmes is CEO of the Disabled children’s charity Building for the Future. She is also the proud mother of Kitty, 19, who has athetoid cerebral palsy, and she is married to Jasper.

Carrie Ravenscroft

Carrie is a queer and neurodivergent artist from London. Her art practice focuses on women’s health, late diagnosis and the mind-body connection, which she communicates through colour, characters and symbolism in detailed, linked artworks. Recent creative projects include a neuroart exhibition in collaboration with neuroscientists at the Kings College ADHD Research Lab. Outside of making art, Carrie is a a mental health support worker and art psychotherapist at Mind, the mental health charity, and volunteers as a psychedelic first aider with the charity PsyCare.