Elena and her colleague Anthony begin to restore order to the myriad books in which Audrey Amiss recorded the details of her life. The painstaking work requires an acute eye for detail, slowly recreating Audrey’s own archiving method.

Cataloguing Audrey

Words by Elena Carteraverage reading time 10 minutes

- Serial

I’m surrounded by boxes. Inside the boxes are scrapbooks, sketchbooks, log books, artworks. Hundreds of volumes, thousands of sketches, seemingly endless pages of scrawled notes and sketches.

I’m an archivist, and that means I learn about people and their lives through the stuff they leave behind. We all create a lot of records in our lives, usually without even thinking about it. Photographs, old birthday cards, love notes, work letters, ticket stubs.

Sometimes that stuff gets put in a folder or forgotten about in a box in the attic, stashed away because the person who wrote it wants to refer back to it or thinks it’s important. Years later, someone else might find it and think it looks interesting, or someone might wonder if there’s some value to all this stuff they’ve kept hold of.

That’s the moment when it might get offered to an archive or library, where it can be preserved and organised so that people can access it long into the future. An archivist is the person who does that organising, working silently behind the scenes so that others can find what they’re looking for.

Carol and Audrey

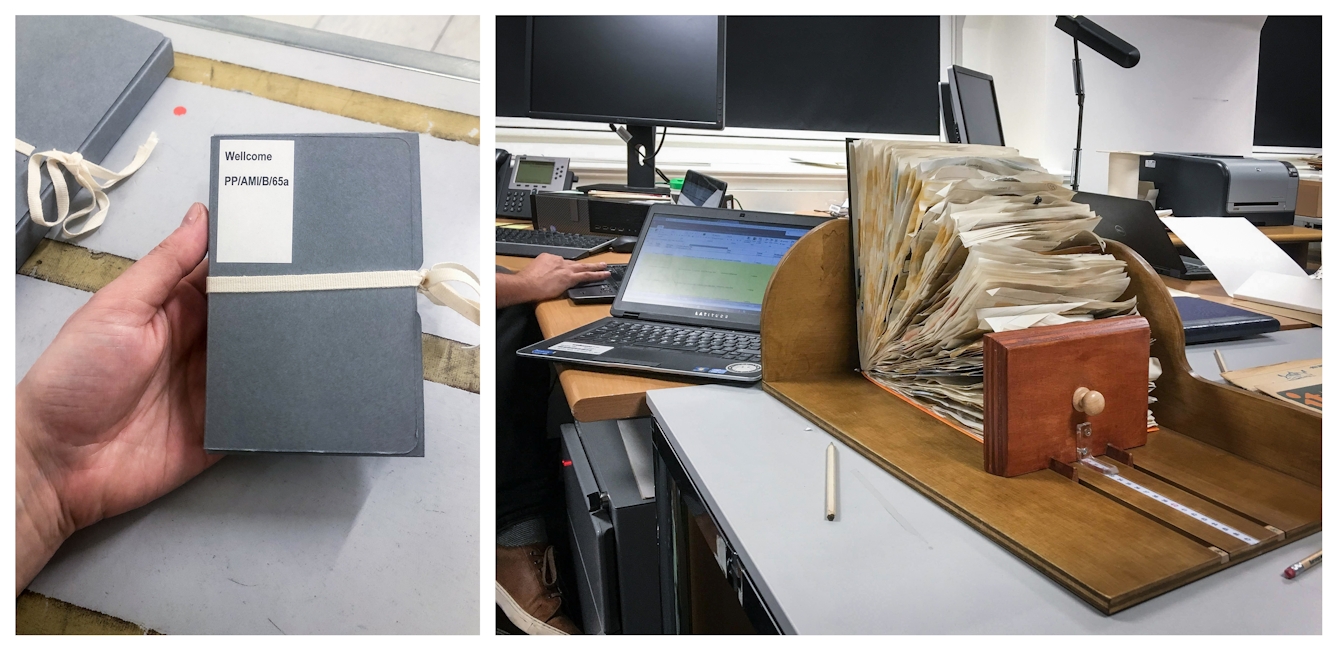

The boxes I’m surrounded by all contain material created by Audrey Amiss, artist and mental health survivor. “Reference: PP/AMI” it says on the boxes. “Personal Papers; Audrey Amiss.”

My job is to go through this material and try to work out what I’m looking at, to find some order to how the material should be organised and arranged, and then find a way to describe each item that it is in front of me. To describe the item, I need to find out key information about it: What is it? When was it created? What is it about?

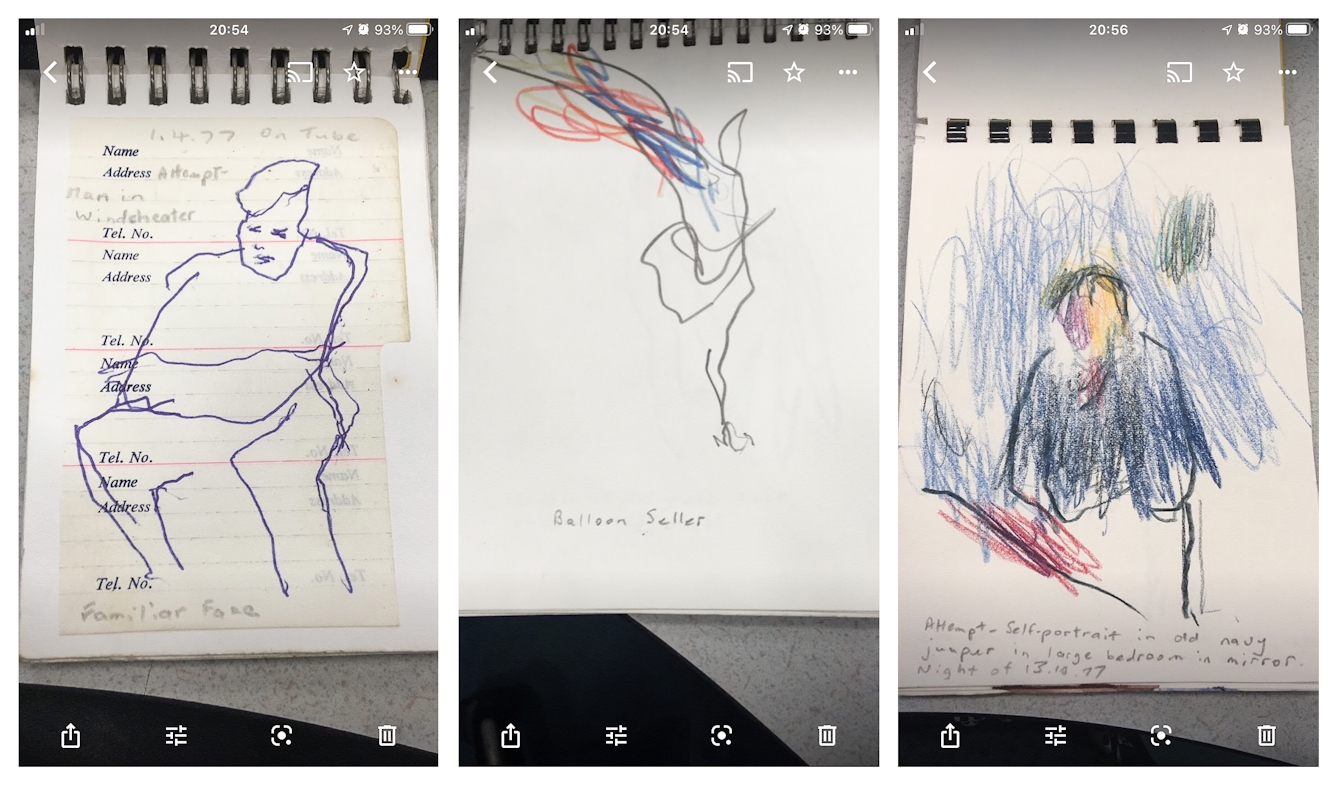

Sketchbook, 1977. Documentation photograph.

This description then forms the catalogue: a guide to help researchers know what material they’d like to look at in greater detail. My job isn’t to transcribe everything in front of me, but to find a concise way to summarise what something is and to group together similar types of materials.

Before even starting the cataloguing, fellow archivist Anthony and I spoke to director and artistic researcher, Carol Morley. Carol Morley won a screenwriting fellowship from Wellcome in 2015 and was introduced to the work of Audrey Amiss. Soon she was immersed in the kaleidoscopic world of Audrey’s archive, and felt that Audrey had found her; Audrey would be her next feature-length film.

Out of this research, Carol would go on to make a film of Audrey’s life, drawing heavily on the archive, which I’ll share more about in the sixth article in this serial. The film became ‘Typist Artist Pirate King’. Its title is what Audrey wrote under ‘occupation’ in her passport.

‘Typist Artist Pirate King’ is a fictionalised account of a road trip between Audrey (played by Monica Dolan) and her psychiatric nurse (Kelly Macdonald), a journey back up north to Audrey’s home in a last-ditch attempt to gain recognition for her artwork.

During the cataloguing work, Anthony and I would meet with Carol. We’d share things we’d found with her, and she’d share things with us. We were each developing our own relationship with the archive and with Audrey from the long hours spent reading her works, and sometimes it felt like talking to each other was the only way to move between the internal world of Audrey and the external world.

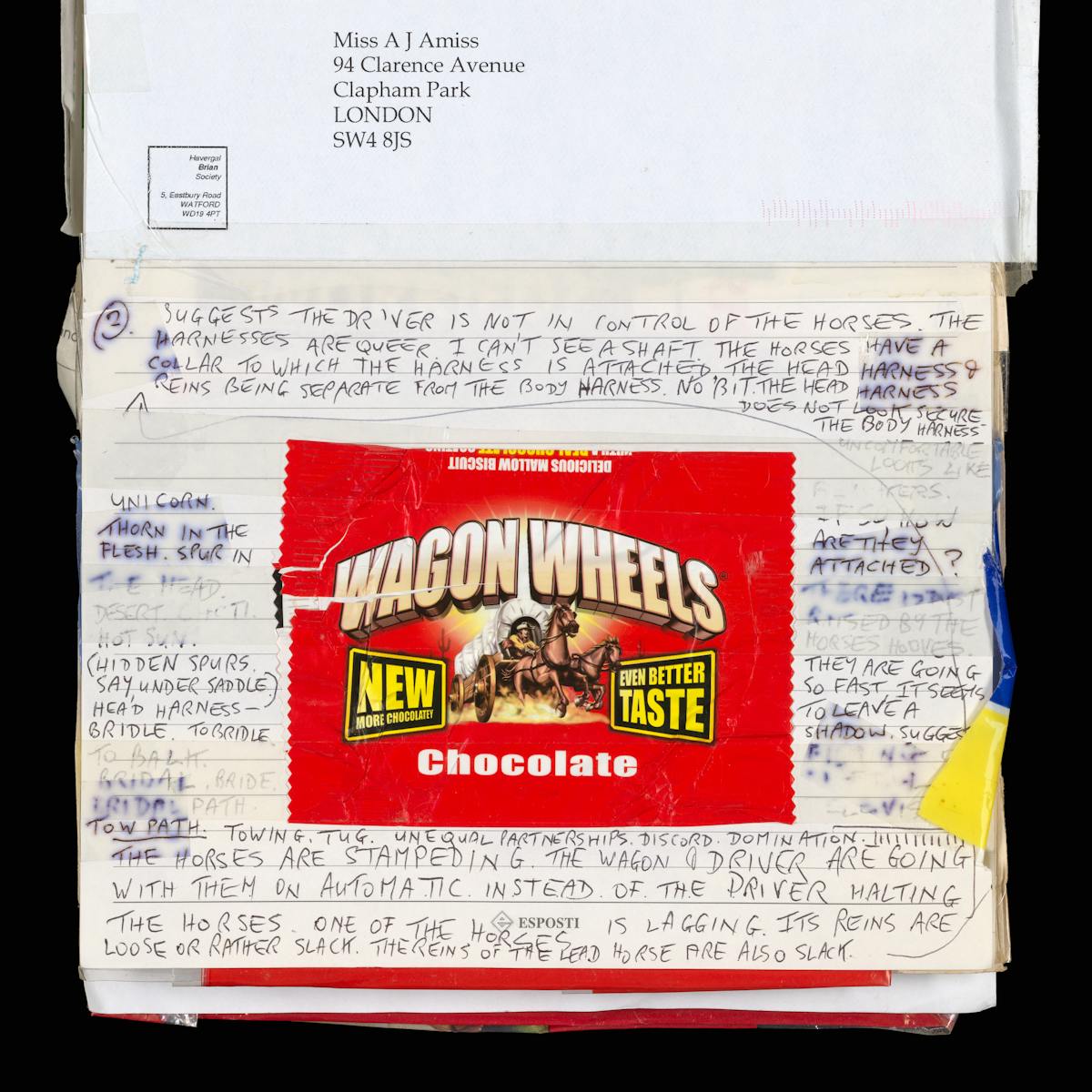

Scrapbook. Documentation photograph.

Cereal, kippers and ice cream

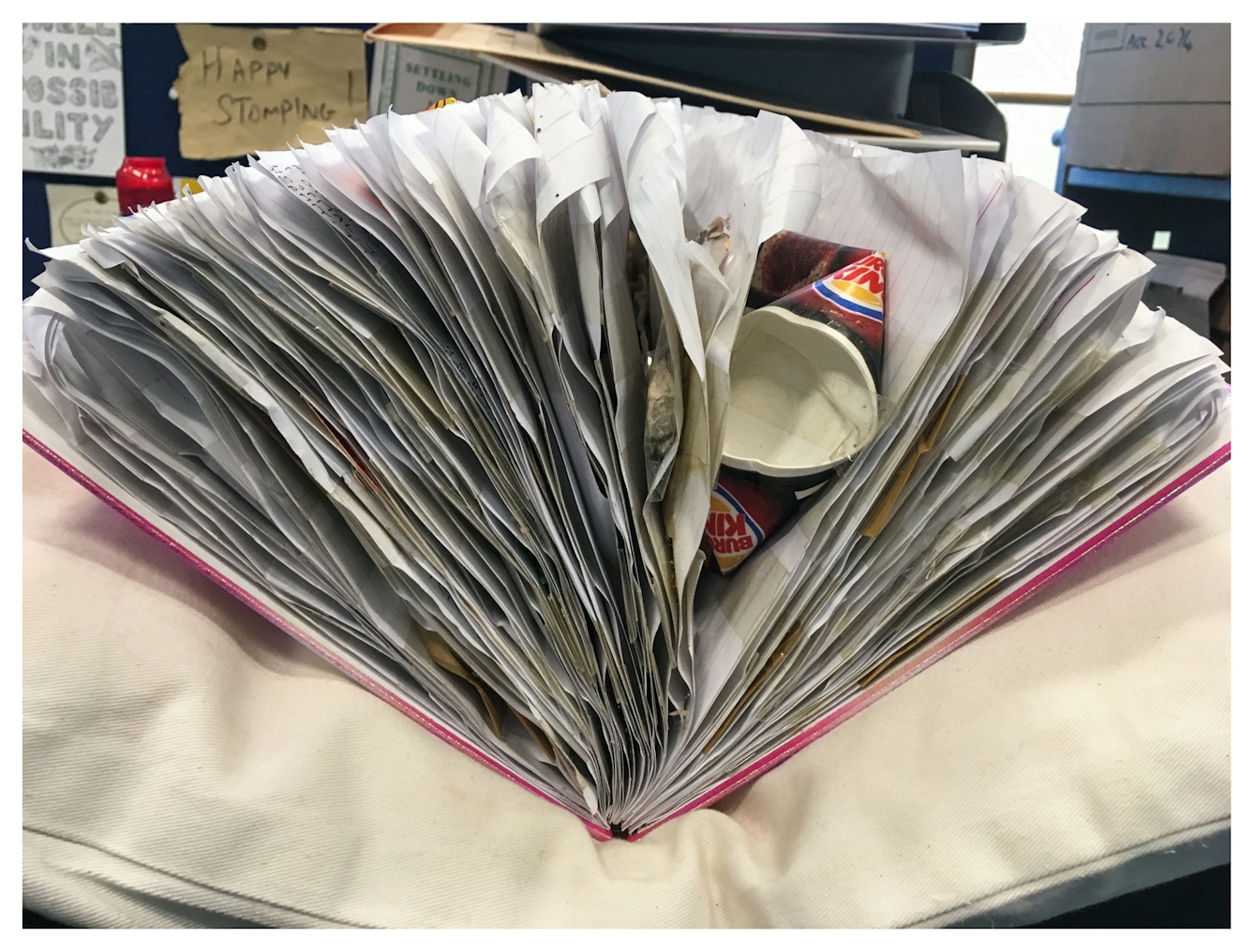

I gently lift a book out of a box. It’s a spiral-bound A4 book, with a garish 1990s-style holographic cover. It is so heavy with food packaging and objects pasted inside that the entire volume bulges, and it looks more like an accordion than a book.

As I open it, there’s a slight smell of kippers and a sticky sound as the pages peel away from food packets stuck inside. On the first page, large red biro letters announce: “CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS VOLUME.” It starts on a Tuesday, which may also be a Wednesday, as the date is recorded as 7/8 June, and then there’s the first item: a Walkers crisp packet. Taste: salty.

Further in the volume, a wrapper from a Solero ice cream is glued down next to the ice-cream stick (“From Abru Traders. Bought yesterday”). The Solero lollipop stick is sellotaped down, and Audrey has drawn long legs coming out of the curves of the wooden stick. Now I’m looking at the back of a woman walking away, one foot slightly raised, and the curves of her hourglass figure.

A note from Audrey: “Torso. Clothed. It would be rigid. Inflexible. The lollipop as well as the wrapper was twisted.” I realise I’ve never properly looked at an ice-cream stick before.

Scrapbook. Documentation photograph.

The rest of the volume contains more food packaging: cereal packets, chocolate bars, microwave meals, toilet rolls. Each piece of packaging is numbered and dated, and the volume contains about a month’s worth of entries. There are over 200 volumes like this, with food and household items and Audrey’s thoughts.

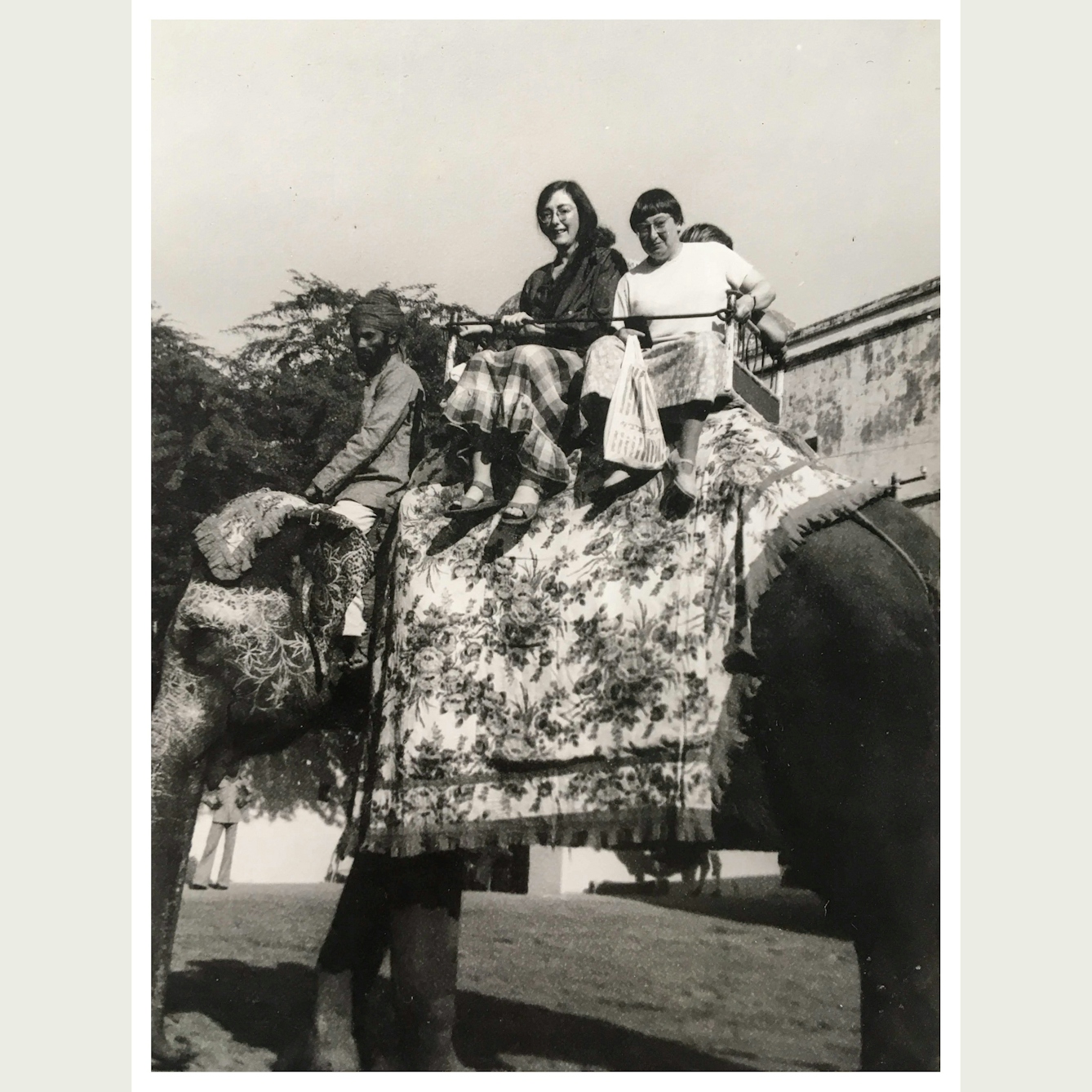

Then there are earlier volumes containing photographs of what captured Audrey’s attention; some are photos from her holidays and travels, of Audrey perched on top of an elephant in Nepal, clasping a Tesco carrier bag, others are filled entirely with photos of objects around the home: a brightly coloured blouse, flowers in a vase, fruit, and a plastic bag.

Over time, junk mail and local-newspaper cuttings start to feature alongside the photos, and then food packaging, until the volumes concertina and fan open from the weight of food packaging.

Holiday photograph showing Audrey (right). Documentation photograph.

Putting Audrey’s archive in order

In the basement stacks at Wellcome Collection, bays of moveable shelves contain row after row of neatly organised acid-free boxes. In order to know what’s in the boxes, the contents are described and arranged by an archivist. This catalogue acts as a map, a way of navigating through vast amounts of information.

Each thing is given a unique reference, a title and a date. By browsing the online catalogue or searching for key terms, someone can find specific items they want to look at in person. The stacks are unrolled, and a member of staff brings up the folder to the library for the reader to look at.

As archivists, we’re working behind the scenes to create information about information, writing brief summary descriptions which state factually what something is, rather than how something feels. We are supposed to aim for neutrality, avoid adjectives, not focus on one detail over another, avoid any prejudice creeping in.

Boxing and cataloguing (left) and measuring scrapbooks (right). Documentation photographs.

Audrey was like an archivist herself; she catalogued things that were happening in her life and carefully arranged the items she ate, letters she sent and sketches she drew according to their function and date.

When the material was found in Audrey’s home after her death, the volumes were scattered across the flat. The first task for me as an archivist was to try and return the material to their original order, which meant putting the books back into date order and arranging the books into their different distinct series, so that all the log books were together, and all the scrapbooks, and so on.

Working together with fellow archivist Anthony, I lift the books carefully out of their boxes and start to arrange them around the room according to the decade of creation, and then the month, and finally sort them by date.

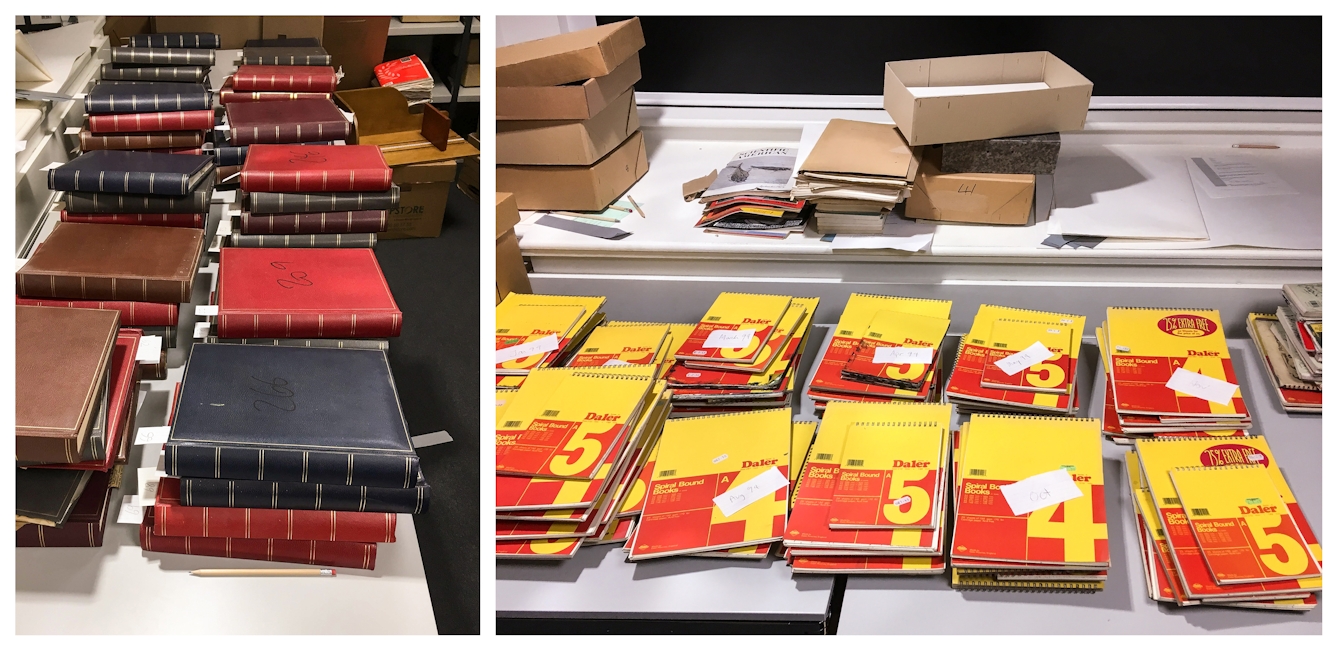

Photo albums (left) and sketchbooks (right). Documentation photographs.

Soon we’re surrounded by clusters of volumes, and we start to notice patterns emerging – a time when Audrey used A3 sugar-paper holiday scrapbooks with images of the seaside and crabs on the front, or a period where she seemed to prefer spiral-bound lined notebooks.

There are patterns in the material inside the volumes too – times where they contain lots of newspaper cuttings of dog races in Tooting and adverts from sales catalogues, or times where Audrey’s meals were all purchased from the local corner shop. There’s a satisfaction to recreating this order.

Some of the earlier volumes don’t have dates, and we peer closely at photographs to try and piece together when the volume might date from. A billboard or the ‘best before’ date on a piece of food packaging can provide clues to dates, as well as the grainy quality of photographs or similarities to other dated volumes.

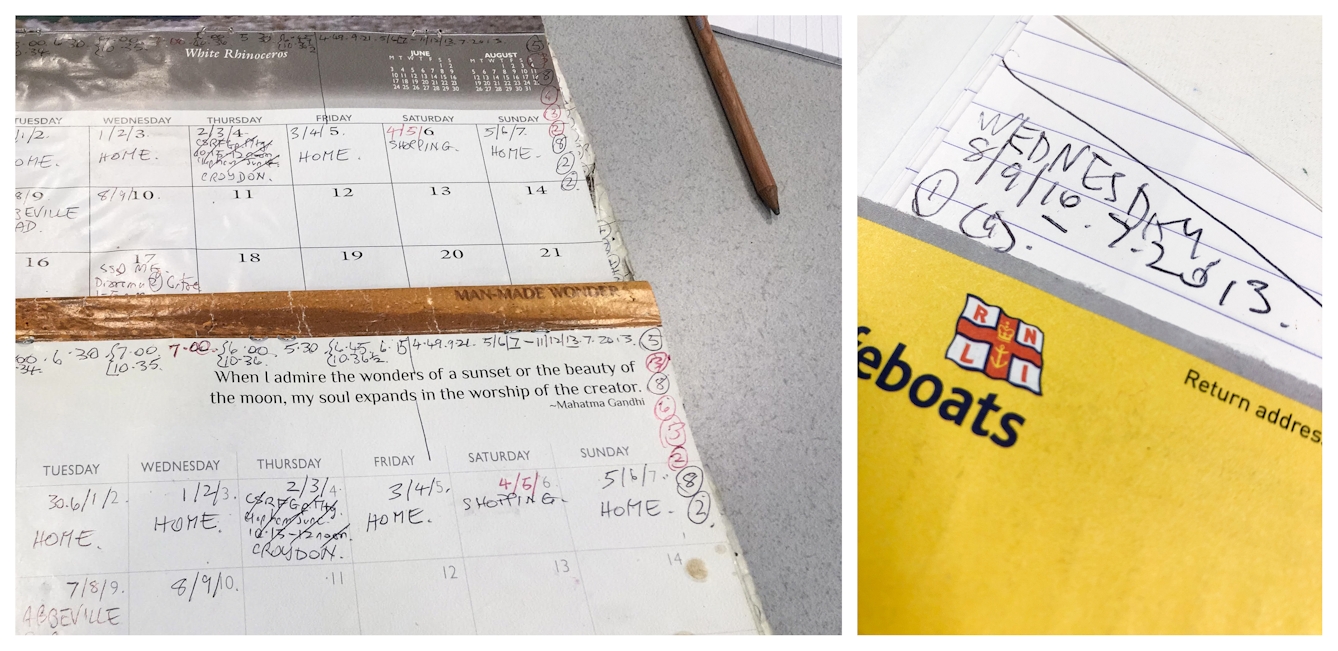

Annotated calendar (left) and dated scrapbook entry (right). Documentation photographs.

Dates can be elusive in other ways too – we know that Audrey was deeply concerned by time and was paranoid that time itself was being controlled or manipulated in a way that was outside her control. In documenting, Audrey seemed to be keeping a record of these occasions, noting when the time on a receipt doesn’t match the time she thought it was, and writing letters with concerns about leap years to MPs.

Audrey used a time scheme she refers to as “double time”, where dates are listed consecutively: 20/21/22 November, for example. We try to honour her dating system in the catalogue data itself, using Audrey’s ways of describing dates in the descriptions and trying to use Audrey’s words as much as possible.

A message to Audrey

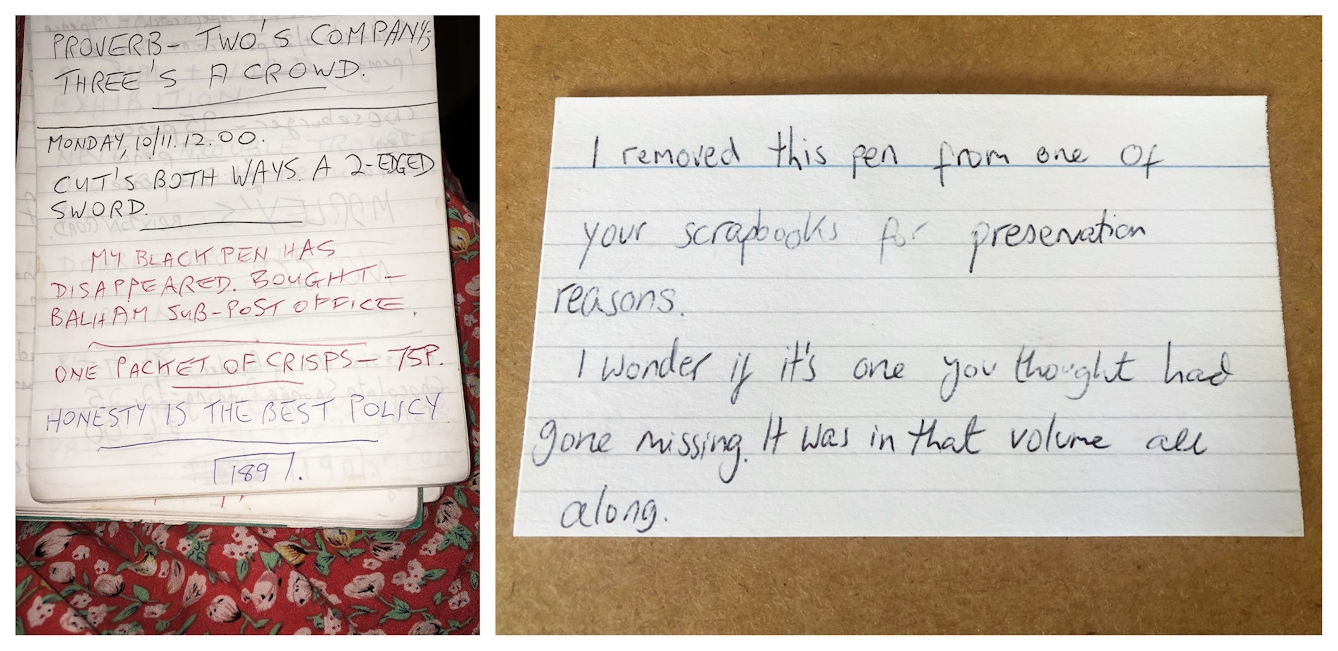

In a log book, Audrey writes that her pen is missing. There’s a sense that she feels someone or something has removed it. Her books are filled with writings in which she tried to find connections – between the faces of famous people, who she sees as other people she knows; connections between words and things and people; long streams of consciousness with word associations – and there is a sense that she feels often on the cusp of making some huge discovery, of finding some pattern in her life that makes things fall into place. There is a seeking, a searching, a yearning in her writing.

Log book (left) and handwritten message to Audrey (right). Documentation photographs.

I catalogue the log book, wondering if she ever found that pen. Later, I’m cataloguing a weighty scrapbook, and as I turn the pages, a black Bic biro rolls out. It is so wedged in that the outline of the pen can almost still be seen as a shadow on the page. I wonder if it’s the same pen she thought had gone missing. In a moment of strange connection, I write a note to Audrey using her pen.

“I removed the pen from one of your scrapbooks for preservation reasons."

“I wonder if it’s one you thought had gone missing. It was in that volume all along.”

I put it in a notebook, where I write down things that come to mind when I’m cataloguing the material. Then I write the catalogue description, stripped back of all the emotion I’ve just felt on finding this pen:

“This volume originally contained a loose black biro towards the end of the volume; this has been removed for preservation reasons.

“This volume has been dated by Audrey.

“Continues from previous volume.”

You can explore the Audrey Amiss archive through our online catalogue. To see the archive, you need to join our library and request to view specific items from the collection.

About the author

Elena Carter

Elena Carter focuses on developing the collections at Wellcome to challenge the way that we think and feel about health. Elena is particularly interested in radical and social histories and material that gives voice to marginalised groups. As Collections Development Archivist, she works directly with people to find the best home for their materials, with a focus on working collaboratively and ethically.