The Isle of Thanet, a small area of England jutting into the Channel, is – because of climate change – set to revert to the island it once was. But this won’t be because of a sudden catastrophe. Flooding will come and go, lasting longer each time. Locals’ lives will, little by little, have to change. But it’s all of us who need to learn from this.

Coasting to catastrophe

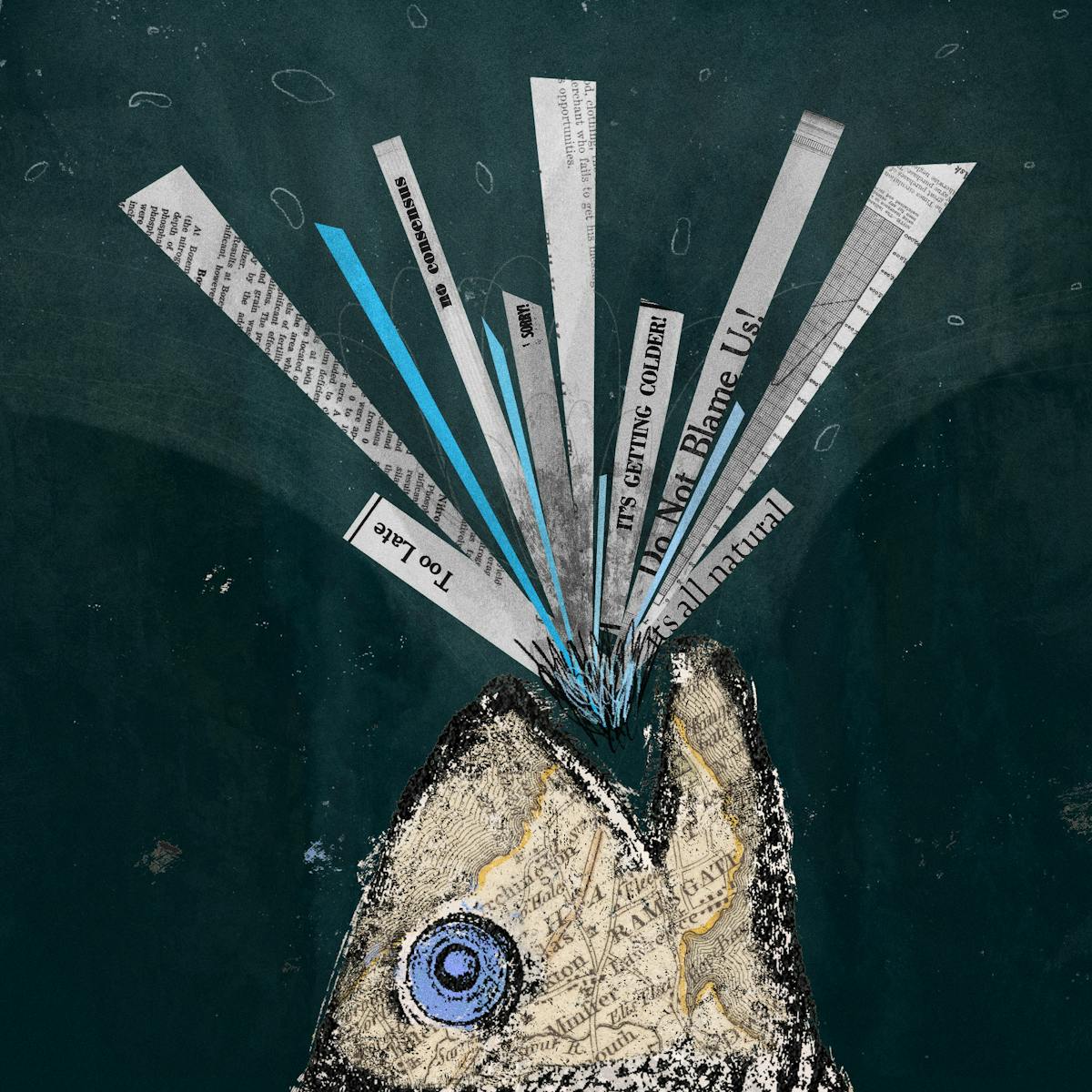

Words by Charlotte Sleighartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

If you move your finger across a map of England to its eastern extreme, you reach a small outgrowth of land, extending from the county of Kent. In real life it’s about ten by ten kilometres, an area known as the Isle of Thanet. As its name suggests, it was once cut off from the mainland by a waterway, the Wantsum Channel, that was navigable by ship as late as the Middle Ages.

The area covered by these historical ghost waters is flat, vast and unloved. Pylons stride across sticky fields of cabbages, bringing electricity from France to elsewhere in the UK. It has the feeling of being only provisionally occupied until the seas rise to reclaim it once again.

Thanet was a stronghold of the Brexit vote; its seriously impoverished inhabitants felt – and feel – abandoned by the political establishment, and kicked back where they could. Its island mentality will, sooner or later, be physically embodied by the refilling of a watery boundary between it and the rest of England.

South Thanet’s Conservative MP Craig Mackinlay appears not to be concerned about this, having consistently voted against measures to prevent climate change. My son’s geography teacher shares Mackinlay’s sanguinity, assuring her class that the return of the waters won’t happen during their lifetime. The research and mapping organisation Climate Central disagrees. By 2030, a flood through the whole Wantsum Channel zone will be a once-a-decade event, from Reculver in the north to Walmer and Deal in the south.

The geography teacher is sort of right, though, inasmuch as she is likely imagining something rather different by way of a flood. When we think of disaster, we think of something total, sudden and complete.

“The Isle of Thanet is flat, vast and unloved. It has the feeling of being only provisionally occupied until the seas rise to reclaim it once again.”

Taking the scenic route to disaster

The apocalypses in this series have threatened annihilation from the mushroom cloud, by surprise Martian attack, or the trumpeting return of Christ. When it comes to floods, our ancient touchpoint is Noah’s near-instantaneous and catastrophic flood; in recent times, some of us picture the towering tsunami in ‘The Day After Tomorrow’ (2004), wiping out Manhattan in one go.

The usual reality is slower and less dramatic, more like what the poet T S Eliot, writing on the Isle of Thanet, described as “not… a bang but a whimper”. A flood event need only be a few centimetres deep to cause major infrastructural problems. Trains between Margate and London already get cancelled due to portions of the track lying underwater at times.

Residents and visitors brush such closures off as anomalies, but science predicts that these flood events will increase in frequency and severity. December 2013 was a near miss, when only a favourable wind direction prevented a storm tide higher than the one that surged inland on a winter’s night in 1953, drowning thousands of people on either side of the North Sea.

With luck and continuing coastal-defence maintenance, no one will drown in future floods. However, as water levels rise and weather events increase in intensity, an afternoon’s inconvenience will become a week cut off; and soon the question surfaces: how soon until next time? A house becomes uninsurable; a business is economically not worth drying out and relaunching.

It’s too late to save Thanet as a continuous and permanent part of the mainland, but as its own history reveals, the landscape and the life it supports have always evolved and changed. The question is how its people and ecosystems can go on to flourish together.

Without adjustment, deepening floods will knock out parts of the road network for longer periods of time. Sewage, which moves under gravity for much of its path, will back up into houses. Electricity supplies will jitter and fail. Things will be out of order for days, weeks. Infrastructure will become subject to breakdown, and with it, the vulnerable will be dragged into progressively more difficult modes of living.

“Even when locally apocalyptic events do occur, the news cycle squashes them down with next week’s stories about a celebrity court case or a football team.”

A stronger society for climate resilience

This is the reality of climate change for richer countries: not a sudden, apocalyptic collapse, but the slow breaking of everything. A teacher can’t drive to school. An IT technician has no power to his router. The bus service to the job centre is cancelled. A doctor cannot go to work because she is busy slopping dirty water out of her kitchen.

Knock-on effects like these are already happening but are rarely attributed to their true cause: items that are missing or more expensive in the shops, services that are intermittent or reduced in availability.

Meanwhile, refugees fleeing climate-aggravated war stagger ashore on the beaches of Thanet – over 28,000 in 2021. Some welcome them, but others fear that any paltry assistance they may receive from the state comes at their own expense. Suspicion, grievance and violence build.

Even when locally apocalyptic events do occur, such as the firestorms of California, Australia, Spain and Greece, the news cycle squashes them down with next week’s stories about a celebrity court case or a football team. If even the conflagration of a town can be smoothed out of our collective memory, what hope do we have of paying proper attention to the incremental changes that are the mark of climate change in rich countries?

The collective imagination needs adjusting so that we see social inconvenience (and worse) as intimately connected with climate breakdown. Apocalypse-watchers of the 17th century saw signs everywhere; their paranoia is mirrored in reverse by our equally ludicrous unconcern – our inability to make the links.

Strengthening social relationships is just as important in developing climate resilience as it is in reducing carbon emissions; the latter, in fact, depends upon the former. Kent Refugee Action Network is a beacon of hope in Thanet, providing mentoring, learning and health support for new arrivals.

By generating hospitality among its volunteers and employees, projects like this (and there are smaller and more local ones) nudge longer-standing locals out of a mentality of self-protection. Generosity breeds confidence, and vice versa.

The effects of climate breakdown are already seeping around us, but apocalyptic imagination is unlikely to help. The Isle of Thanet is a model of Britain in miniature, showing how, in climate change, everything – and everyone – is connected.

About the contributors

Charlotte Sleigh

Charlotte Sleigh is an interdisciplinary writer and practitioner in the science humanities. Her most recent book is ‘Human’ (Reaktion, 2020). She is Honorary Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and current president of the British Society for the History of Science.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.