Many of the volumes Audrey created include elements that degrade: Sellotape, traces of food, thick, water-based glue. Elena talks to conservator Stefania about the balance between intervening to prevent Audrey’s work from deteriorating, and keeping items as close to their original state as possible.

Conserving Audrey

Words by Elena Carteraverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

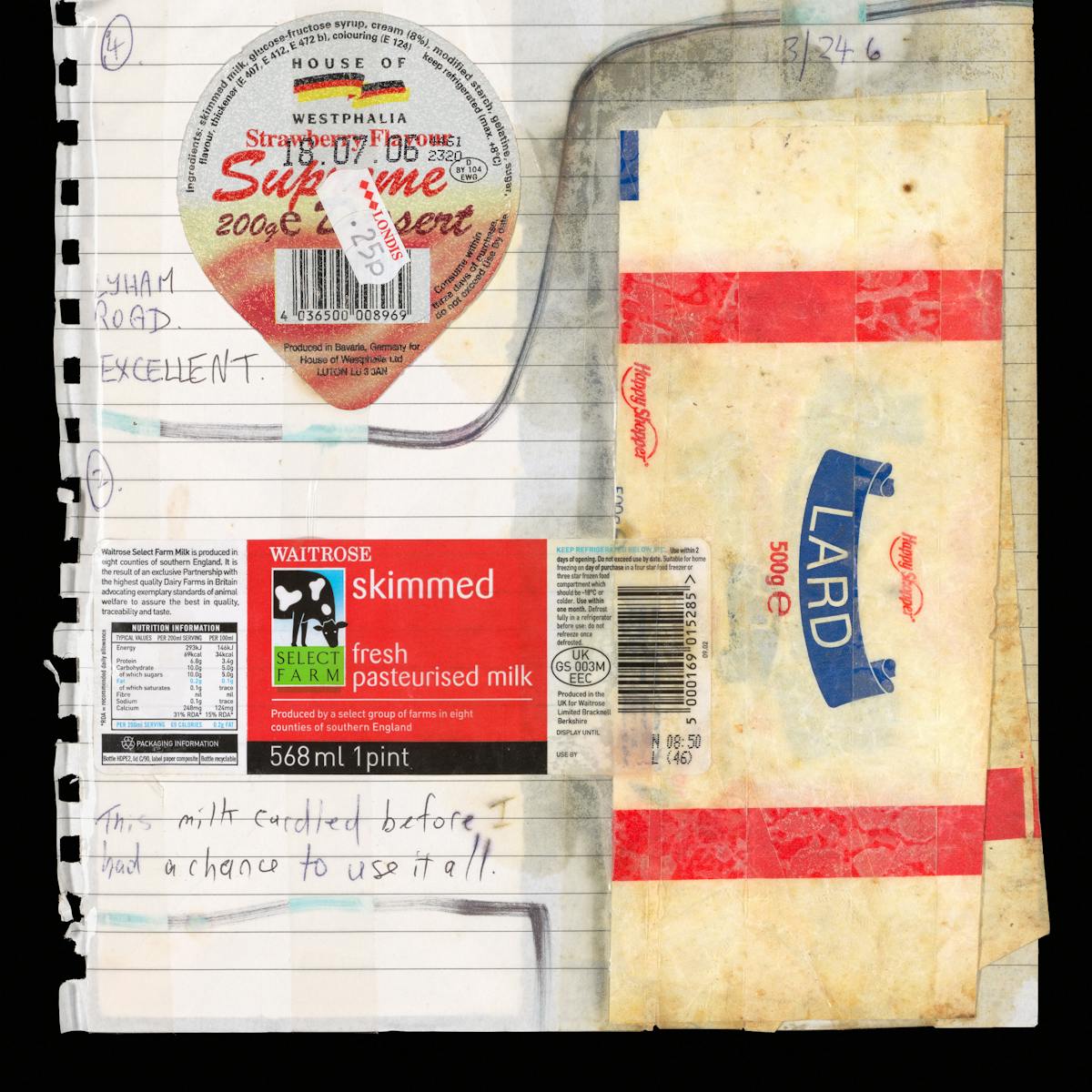

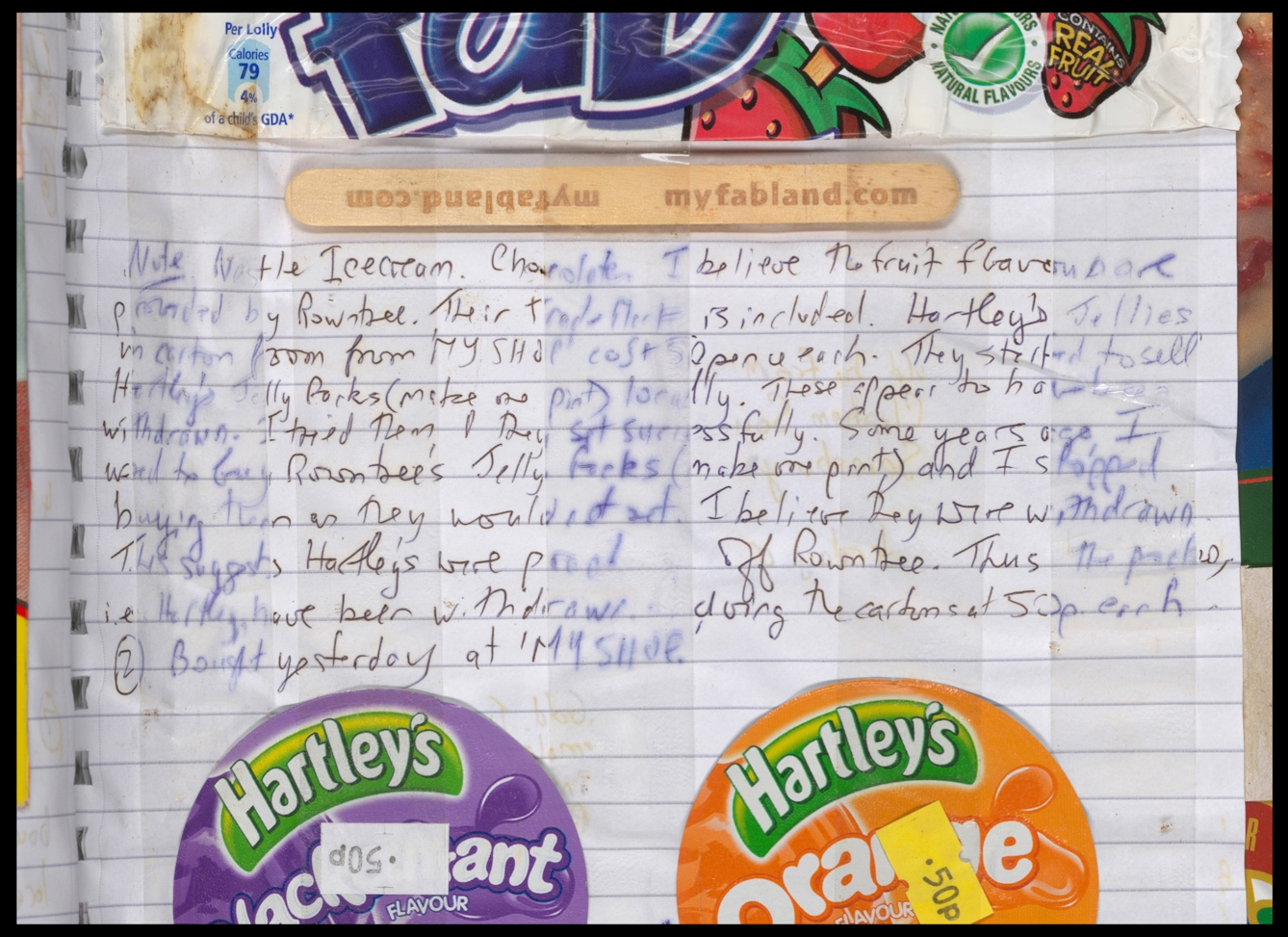

I’m standing in the conservation studio at Wellcome Collection with conservator Stefania Signorello. One of Audrey’s scrapbooks is in front of us, balanced on a series of cushions and supports. Stefania delicately turns a page and peers closely at a sugar packet, which has been sellotaped in place. The sugar, now ageing, has created a brownish greasy stain on the opposite page, where some of Audrey’s writing in a blue biro has blurred and become almost illegible.

Everything ages and changes over time, whether a medieval manuscript or a diary from the 1980s. Conservators work to slow that damage so that material survives much longer. In some cases, it’s almost a process of fighting the inevitable process of ageing and decay.

It’s also often an invisible process that happens behind the scenes, a process of delicately removing dirt from surfaces, of keeping the stores at a low temperature and monitoring for pests, repairing tears and rips in paper. Both visible and invisible repairs need to be made at times, but conservators try to avoid interfering with the works in a way that is overly noticeable, using processes that are, for the most part, reversible.

One of Audrey's scrapbooks in Conservation, undergoing an assessment to create a new bespoke archival housing.

The scrapbook in front of us is bulging open and thick with the weight of pasted-in packaging. There’s mould on some of the pages, the Sellotape has aged and is losing its stickiness and some of the pages stick together with the residue of dried-on food waste.

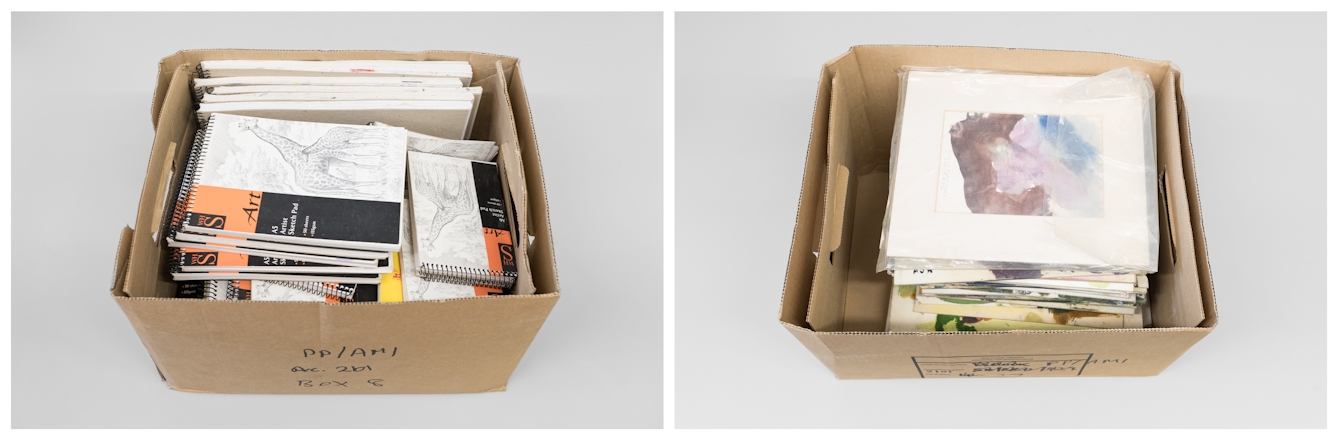

When we decided to acquire Audrey’s collection, we had to ask ourselves whether we could even care for this material and make it accessible. There are hundreds of volumes, filled with different materials degrading at different rates, plastic packaging, sticky residue from food sealing pages shut.

And the challenge was not just finding ways to stabilise and treat Audrey’s works themselves. We also had to consider the risks of potentially introducing hazardous material to our library stores, and whether volumes of old food packaging might attract unwanted insects to nibble their way through neighbouring manuscripts and archives.

A selection of Audrey’s sketchbooks as they arrived in Conservation, before each item was rehoused in a custom-made archival box.

Custom-designed care for Audrey’s work

Stefania shows me a box she had made for one of the largest scrapbooks in the collection, a lined notebook propped open at a 90-degree angle by all the packaging pasted inside. It’s a huge, grey, acid-free square box with an archival tape ribbon tied in a bow around it.

Stefania unties the ribbon delicately and uses both hands to lift the lid off the box, revealing the volume itself wrapped in special conservation-grade tissue paper. The conservation packaging has all been custom-made and measured, there’s hand-stitching in places, and it’s all been specially designed to make sure that the volumes are supported and kept safe.

Another box contains a volume that’s been sealed in a bag with very low oxygen content, a bit like winter clothes put away in a compression storage bag, though the items themselves are not compressed by this method.

Left: Stefania (left) working with her colleague Sarah to rehouse Audrey’s sketchbooks. Right: Tracing the outline of a scrapbook onto a polyester sheet in order to create a custom-made, long-term storage solution.

Stefania wonders aloud what Audrey might have thought about all the efforts being made to preserve these items.

Stefania explains that she selected a few volumes to seal in this way to reduce the air getting to the material and to slow the decay of the works even further. We can only do this for a few items, she tells me, as the seal will need to be cut open any time someone wants to view the book in the library. She’s also making sure that the volumes are prioritised for digitisation, so that a snapshot exists of how they look now.

The boxes are beautiful objects in themselves. In the stacks, row after row of grey acid-free boxes are carefully marked up and numbered, each a slightly different shape, each housing an individual volume.

In Audrey’s home, these books had been stacked up on the bed, on the floor, piled high on top of every surface. Repacking, cataloguing and organising them is a process of caring for them, but also a process that has changed the objects in some way, validating them as items worth preserving, as well as sanitising them, sanctifying them, and chronicling them.

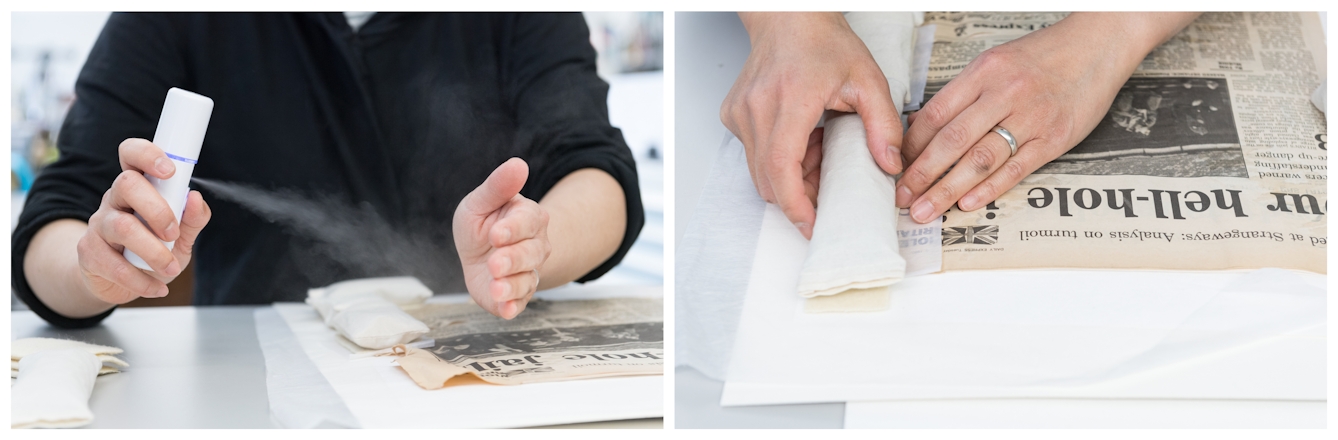

Left: In one of Audrey’s earlier scrapbooks, conservator Satomi is working with Stefania, lightly moistening the creased newspaper to relax the paper fibres. Right: Once relaxed, the paper is weighed down, enabling it to dry flat.

As with the cataloguing work, the question of what Audrey might have wanted is always just under the surface, and Stefania wonders aloud what Audrey might have thought about all the efforts being made to preserve these items. I would really like to show her my conservation work and say: What do you think? Should I change anything?

Imagining Audrey at home

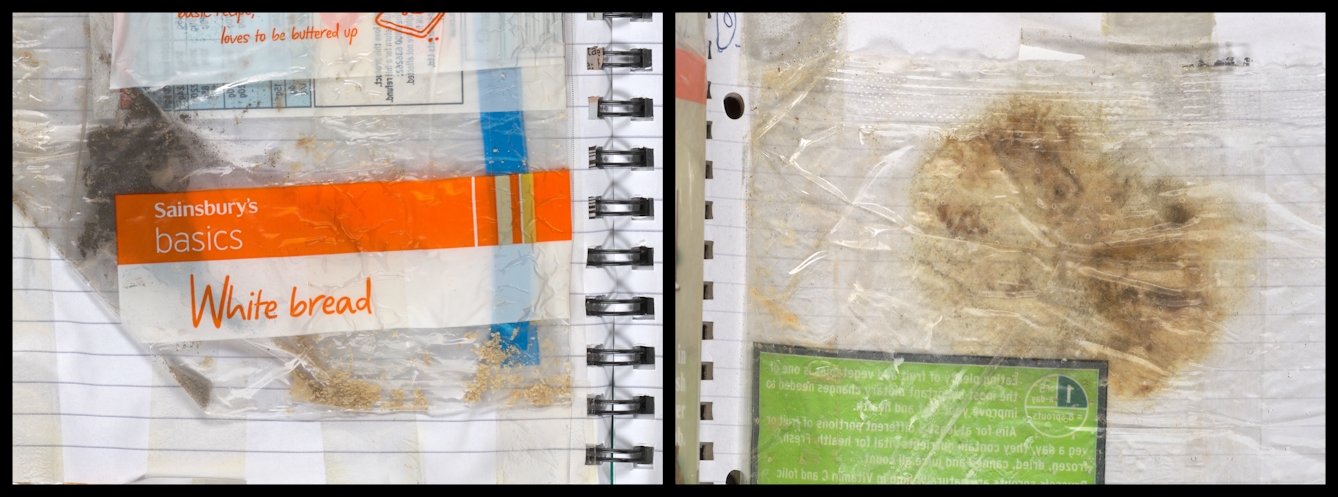

Stefania explains to me that she made the conscious choice to not interfere too much with the material itself. While it has been intricately repackaged and boxed up, cleaning or repairing the pages of the volumes has been minimal. If there’s mould there, it’s because Audrey was eating; it reflects how she worked in a specific way and collected things together in her home.

Audrey was tearing the paper with a pencil because that was the way she was working, sketching with a heavy pencil that ripped through the page. Stefania feels strongly that it wouldn’t have been right to repair those tears or to remove food marks or mould, that you’d lose something of the authenticity and realness of the works if you did so.

Left: PP/AMI/D/193: Scrapbook. Right: PP/AMI/D/202: Scrapbook. Details of food residue and mould trapped within the food packaging.

She points to the Sellotape on the page. It runs from the top to the bottom of the page to stick down a crisp packet and a yoghurt lid. Audrey has written extensive commentary next to the food packaging; some of the writing is underneath the sticky tape and some of it is on top and starting to blur.

Traditionally, conservators would delicately remove sticky tape when it’s been used historically to badly repair a document – but that wasn’t an option here. The tape is intrinsic to the item, part of the collaged piece itself; it holds the works in place. We couldn’t remove all this tape, and if you did, you’d lose so much more of the work.

Opening a photo album, Stefania shows me a heavy residue that has stained the interleaving pages. It’s from the wet and thick glue used to paste in newspaper cuttings and photographs, and it marks the centre of all the pages through the volume. The pages are wavy and stiff with glue.

PP/AMI/D/191: Scrapbook. Detail of Sellotape causing the handwritten ink to bleed and fade.

“It tells us how she was working,” Stefania tells me excitedly. You can tell she was pasting things quickly and using a lot of glue, and then closing the book shut before the glue had even dried. In this way, the conservation work feels almost like a forensic project, piecing together how Audrey was creating and what her process was, adding layers of meaning to the materiality of the objects themselves.

We’ve both paused for a second as we look at the volume, and I know we’re both picturing Audrey at home, cutting a fragment of a newspaper with a precise concentration, the smell of wet glue in the air as she sticks the item down and closes the volume shut.

“That’s why we keep things as they are,” Stefania says. “I don’t want to lose the imagining of Audrey in her home.”

You can explore the Audrey Amiss archive through our online catalogue. To see the archive, you need to join our library and request to view specific items from the collection.

About the author

Elena Carter

Elena Carter focuses on developing the collections at Wellcome to challenge the way that we think and feel about health. Elena is particularly interested in radical and social histories and material that gives voice to marginalised groups. As Collections Development Archivist, she works directly with people to find the best home for their materials, with a focus on working collaboratively and ethically.