Eimear McBride’s blistering new book ‘Something Out of Place’ unpicks the contradictory forces of disgust and objectification that control and shame women. In this extract, she reflects on the deadly consequences of misogyny in the wake of the murder of Sarah Everard and argues why advising women to simply “stay indoors” is wrong.

Dangers inside and out

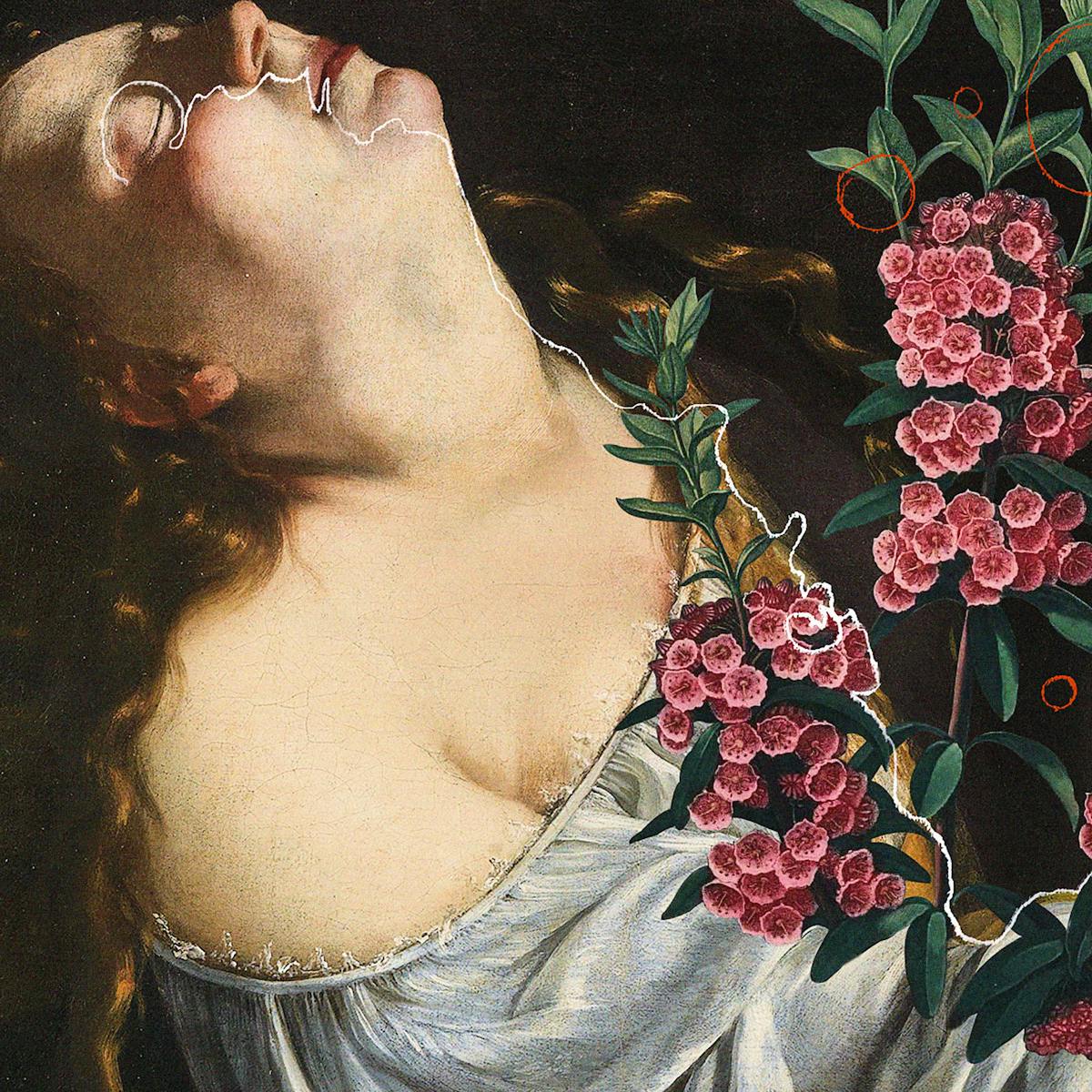

Words by Eimear McBrideartwork by Alexandra Gallagheraverage reading time 5 minutes

- Book extract

Just as ‘Something Out of Place’ was going to print, Sarah Everard was kidnapped and murdered in south London. She was only walking home from her friend’s house, but because she was a woman, alone in the street after dark, she became number 119 on the list of women murdered by a man in the UK in the previous 12 months.

While the hunt for her killer progressed, women were warned to stay indoors. This was their place and the great outdoors at night was not. The awful arbitrariness of Sarah Everard’s abduction and killing – and coming after a year of coronavirus restrictions in which women have been doubly restricted by the dangers of being outside after dark – led to an eruption of grief, fury and frustration.

Women shared their stories of harassment, abuse and assault. They spoke of their fear and anxiety as well as their utter exhaustion at having to live in a constant state of hypervigilance.

Who habitually walks home in the dark with their keys between their fingers, looking over their shoulders and always ready to run? they asked. The universal reply was, Who hasn’t?

‘In the Beginning’.

Why, they asked, must one half of the population live without the basic freedom of movement afforded so unquestioningly to the other? And why is violence towards women seen as a problem for women alone to solve when women are not the perpetrators?

Then a Metropolitan Police officer, Wayne Couzens, was charged with Sarah Everard’s kidnap and murder, and the police force themselves decided that the best way to deal with breaches of coronavirus restrictions at a vigil held in Sarah Everard’s memory on Clapham Common, near the site she was last seen alive, was to break it up, violently.

This led to shameful scenes of women being thrown to the ground, cuffed and dragged away from a peaceful act of public mourning. It stood in stark contrast to the discretion and solidarity adopted during the policing of the previous summer’s, equally restriction-breaking, Black Lives Matter protests.

Might this be because racism is perceived to be a volatile political issue, with deep institutional roots and the potential to cause major social disruption, while misogyny never is? I think so. After all, misogyny has always been the most socially acceptable hatred, relegated to the domestic and private realm and, more often than not, just seen as a bit of a joke.

‘Sacrilege of She’.

Misogyny has always been the most socially acceptable hatred… more often than not, just seen as a bit of a joke.

Men who murder out of it are not viewed as representatives of a deep-seated, institutional blindness to the essential humanity, rights of and wellbeing of women. They are excused and explained away as weirdos and anomalies. Their hatred of women, their desire to do harm to their bodies, either physically or sexually, is simply not taken seriously. It’s not even seen as hatred and, most often, it is considered to have been provoked in the first place.

And, let’s face it, when a crowd of grieving women don’t do what they’re told, it’s pretty easy to throw them to the ground, physically restrain them and cart them away. I mean, that’s how it’s always been, hasn’t it? Do what you’re told, or I’ll give you a smack.

So, if even the police do not recognise women’s right to protest the threat of violence and harassment under which they continually live, then who does? Who will?

‘Turn Inside Out and Swallow Whole’.

A war is being waged on women

In the weeks after Sarah Everard’s murder, the World Health Organization published a report stating that one in three women globally experience physical or sexual violence during their lifetimes. That’s about 736 million women’s bodies that have been subjected to violence. That is 736 million women’s lives that have been for ever changed by violence and by a violence that can be inflicted upon them solely because they are women. We didn’t start a war, but a war is being waged on us, nonetheless.

Staying indoors is not the answer – most of it happens in there anyway. The outdoor life isn’t for us either, it seems – not according to the police – while in the media, online, everywhere we can be seen and heard, we are just inviting our own abuse and silencing, apparently. The willingness to passively accept this as the status quo for women is a stain on contemporary society and an affront to human dignity.

So then, to all those who have never been bothered to seriously think about the cancerous implications of misogyny for women, either individually or collectively, or for our society as a whole, I have a question. Two questions.

If you, as a person of flesh and blood, thought and feeling, who doesn’t want to be murdered or raped, who doesn’t want to be hurt or humiliated, or live in the constant fear of it simply for inhabiting the body you do, who doesn’t want to have to rear your daughters into the expectation of eventually joining this endless malevolent cycle or your sons to feel eternally implicated in its perpetuation, in short, if you were us, women, what would you do? And what are you going to do now?

‘Something Out of Place’ is out now.

About the contributors

Eimear McBride

Eimear McBride is the author of three novels: ‘Strange Hotel’, ‘The Lesser Bohemians’ and ‘A Girl is a Half-formed Thing’. She held the inaugural Creative Fellowship at the Beckett Research Centre, University of Reading, and is the recipient of the Women’s Prize for Fiction, Goldsmiths Prize, James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the Irish Novel of the Year Award. She lives in London.

Alexandra Gallagher

Alexandra Gallagher is an award-winning British multidisciplinary artist whose work takes the form of collage, street art, prints, photography and painting. Her work celebrates the surreal and sublime. Working between the realms of memory, dreams and experience, her work looks beyond our subjective limits and often tells a story of inner imagination and thought. In 2016 she was awarded the Saatchi Showdown Surrealism Second Place Winner and the Secret Art Prize Runner-Up Winner. More recently she was a London Contemporary Art Prize 2018 finalist and shortlisted for the Rise Art Prize.