The material in Audrey Amiss’s collection is fragile, and vulnerable to deterioration. So, to ensure that people can look without touching, digitising it is essential. And that, of course, also means that anyone, wherever they live, can have access to what Audrey created. Elena explores the bespoke process designed specifically for Audrey’s archive.

Digitising Audrey

Words by Elena Carterphotography by Thomas S G Farnettiaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

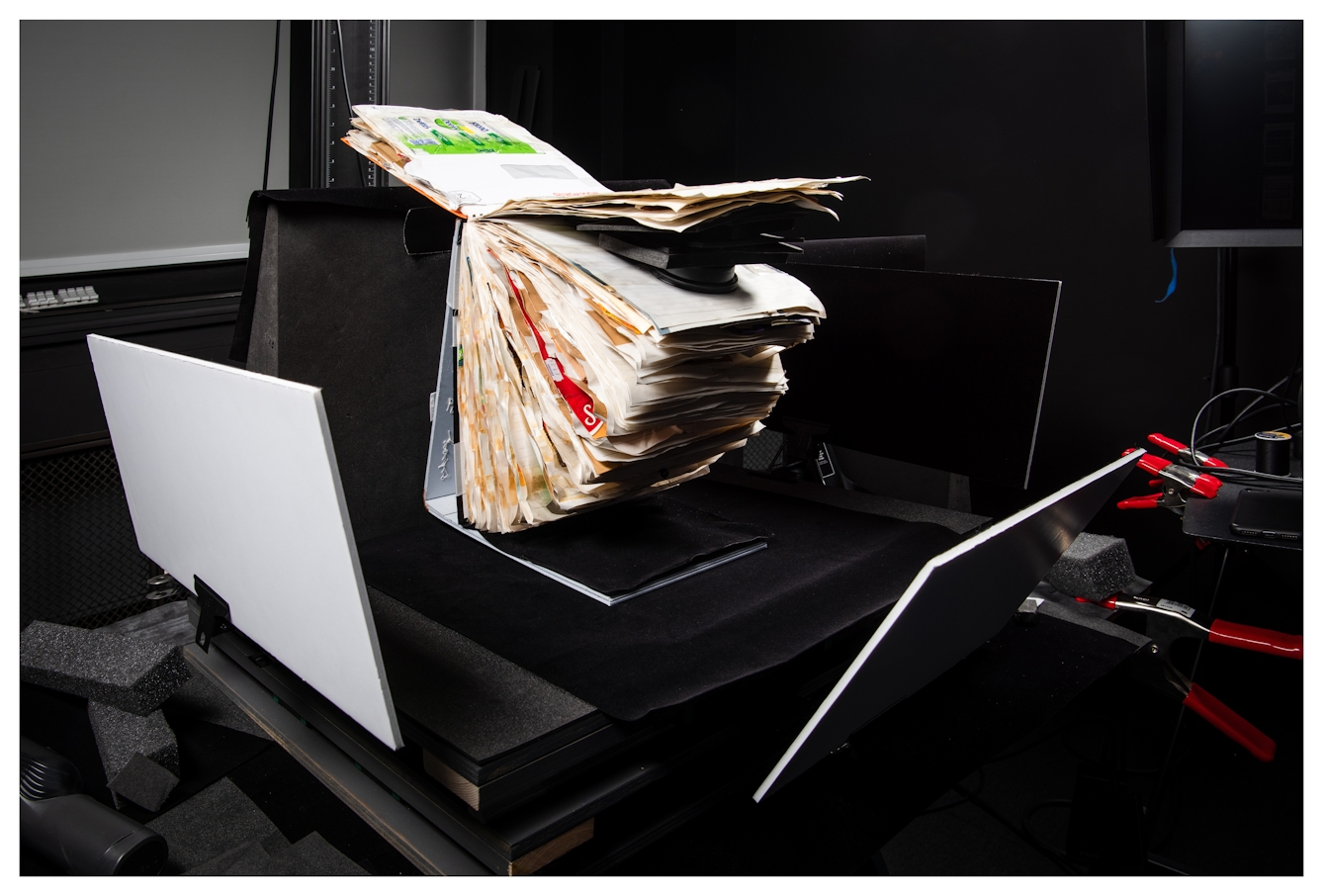

In a darkened room, a large scrapbook is sitting beneath bright overhead lights. A camera is pointing down on the opened page of the book, which is cradled in an elaborate bookrest.

“We’re creating digital negatives, frozen in time – a time stamp, of sorts,” Tom says. Tom Farnetti is a photographer at Wellcome Collection.

As he explains, the process of digitising is the conversion of something analogue – such as a book, manuscript or archival record – into digital form. This means that a digital surrogate exists of physical material held at Wellcome Collection. It helps to protect fragile material from over-handling, and also means that material can, hopefully, be accessed more readily online.

Tom’s been spending a lot of time recently digitising Audrey Amiss’s scrapbooks. “We’ve been photographing the most fragile and complex volumes first,” he tells me, “but it can take a whole week just to digitise one volume cover to cover.”

Tom’s studio setup, fine-tuned to care for Audrey’s scrapbook collection during the process of creating digital facsimiles.

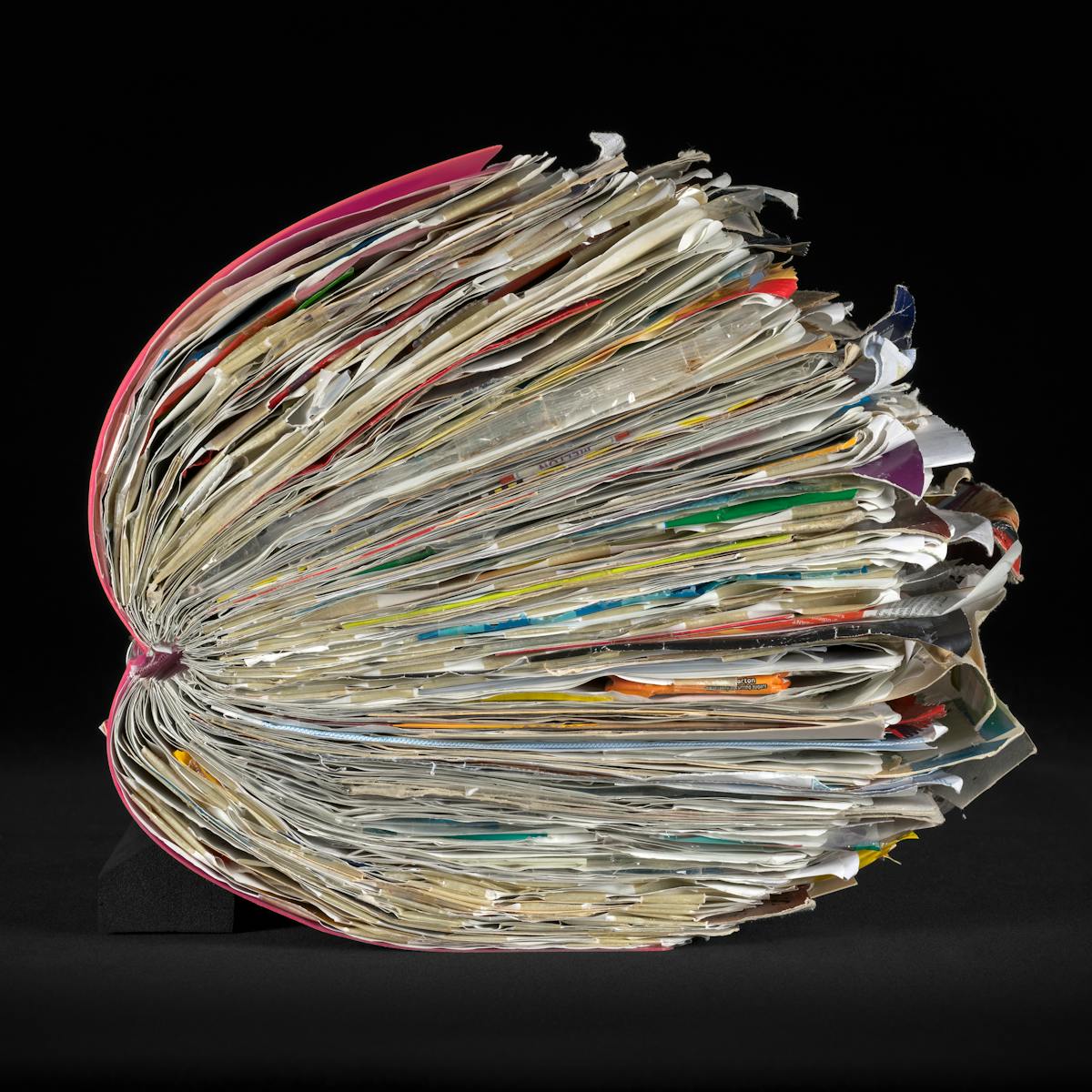

I’m struck by the journey these volumes have already been on. They started life as cheap lined notebooks on sale in WHSmith’s. Then Audrey filled each one laboriously with food packaging and ephemera that caught her eye, alongside extensive commentaries on the aesthetics of the design, her own mental health experiences, and her thoughts on the taste of the items.

After each volume was filled to the point of bulging open, with every page covered, Audrey would start a new book, adding the old volume to the piles growing around her in her flat. When Audrey died, these volumes were found by Audrey’s family, who offered them to Wellcome.

Since the volumes were packed up and brought to Wellcome, the process of cataloguing the works has taken place, followed by extensive rehousing and collections care. Now attention is turning to digitising the material.

Photographic challenges

Even since I first started cataloguing the materials a few years ago, some of the items have degraded or changed in some way. Sellotape has come unstuck, words have faded on the page, and food residues have seeped through pages. Till receipts in account books are fading, the ink disappearing fast.

Bookrest created with Stefania Signorello in Conservation to gently support the larger scrapbooks during photography.

We knew when we took the collection in that it would change with time, and that we’d need to think carefully about how to handle, access and store the items. Digitisation, then, allows us to take a snapshot of how the material looks at this moment in time, before any further inevitable deterioration occurs.

But it’s not as simple as sticking the material under a camera and photographing each page, as Tom explains to me. Although the output is a digital image of the volume, the whole practice of photography – using lighting, flags, supports – is utilised to get to this point.

There are added complications with photographing Audrey’s collection, as this isn’t like photographing a standard book or manuscript. “The scrapbooks don’t fit the traditional setup. The pages are deformed, curved and twisted by the items Audrey sellotaped inside and therefore no longer lie flat.”

We decided it would be better to not interfere with the way Audrey created the volumes and what she chose to be visible.

Photographer Thomas Cox building the micro-adjustment table which helps to safely position the scrapbooks under the camera, greatly reducing the need to handle them.

Tom shows me the bookrest that Stefania in Conservation built for him to use to photograph the items, allowing him to digitise volumes that are propped open at a 90-degree angle. The scrapbook stands upright on its edges, and the stand safely supports the book in this position. Tom gestures to a special table which was built to reduce actual handling of the volume itself, showing me how it rotates carefully and slowly so that he can focus on each part of the book.

“We’re dealing with randomly bound, highly reflective materials taped to pages that don’t always sit flat, inside a scrapbook that won’t sit on a table without additional support,” Tom says, almost with a smile at the challenge this presents.

Lots of the material in the scrapbooks is glossy – plastic wrappers, Sellotape, shiny foil packaging – things that don’t photograph all that easily, as they are reflective. The tactile and three-dimensional nature of the scrapbook creates shadows and can mean that detail on the page is lost and that it’s hard to get everything in focus.

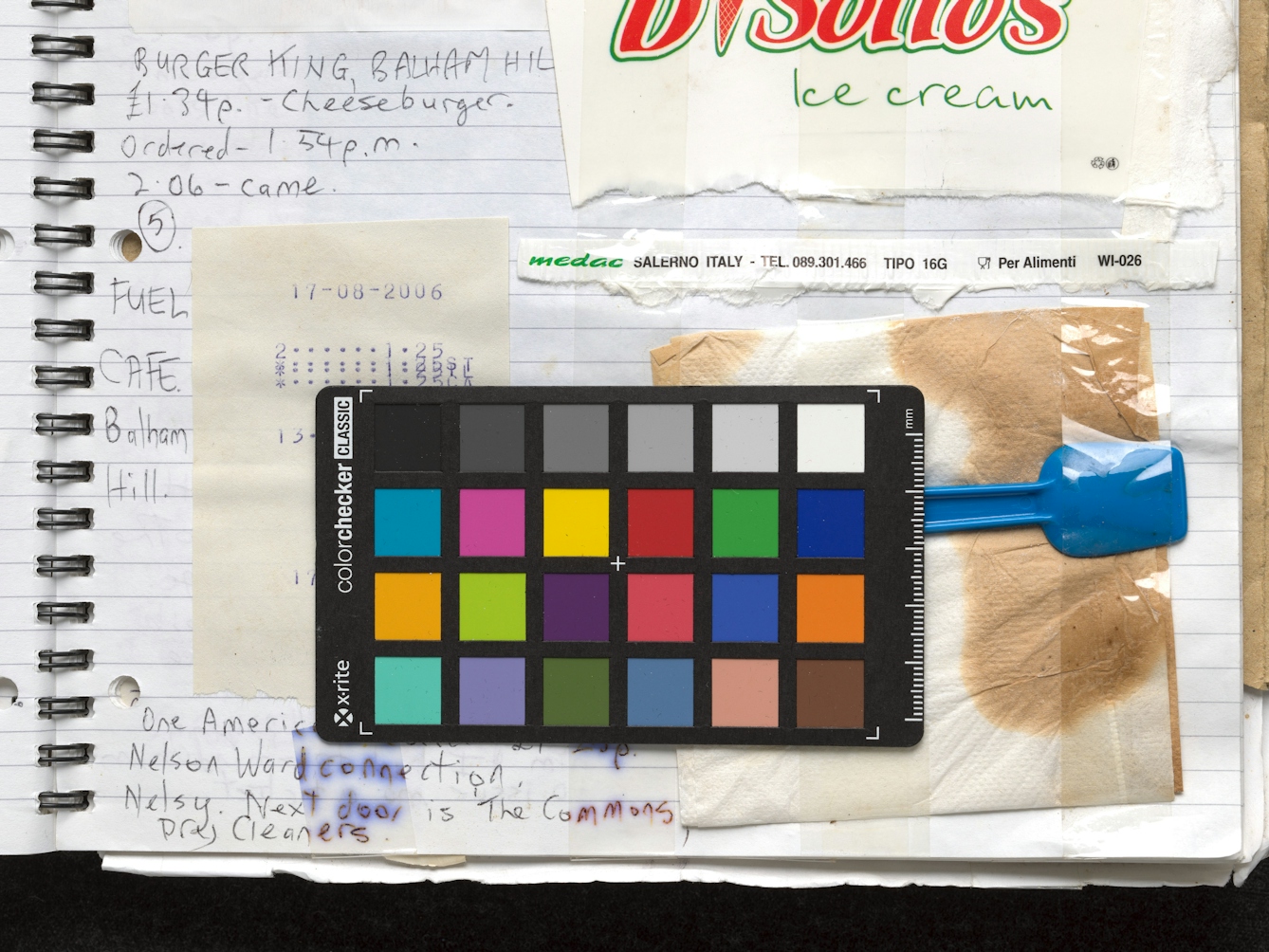

“We have to shoot maybe three shots of one page at different focal distances and then merge these together in the software later,” Tom tells me. “To overcome the challenges that are brought about by the glossy materials, we capture each page from a second lighting setup, changing the direction of the light. This allows us to composite the detail that would otherwise be lost behind the reflected highlight of the first setup.”

Video demonstrating the shine-removal technique used by Tom to reduce the glare from reflective materials and at the same time reveal the handwritten text beneath.

Reflecting Audrey’s process

Tom tells me that digitisation is a technical rather than a creative process, but I disagree – there is creativity in the process he describes of photographing and rephotographing the pages to get the right composition of the page.

It makes me think of Audrey’s process of creating the scrapbooks themselves, of collaging and pasting and arranging items in a way that she found aesthetically pleasing. Tom’s system of digitising the volumes seems to mirror this in some way, as he splices together different composite images to create a replica of the scrapbook page itself.

I think of Audrey’s early photo albums too. Some of these photo albums are filled with similar images, different angles of a bar of soap, page after page of photos of a tree in the garden. You can imagine Audrey clicking away on her camera in quick succession, and I think of Tom sitting in his darkened photography studio doing the same sort of thing.

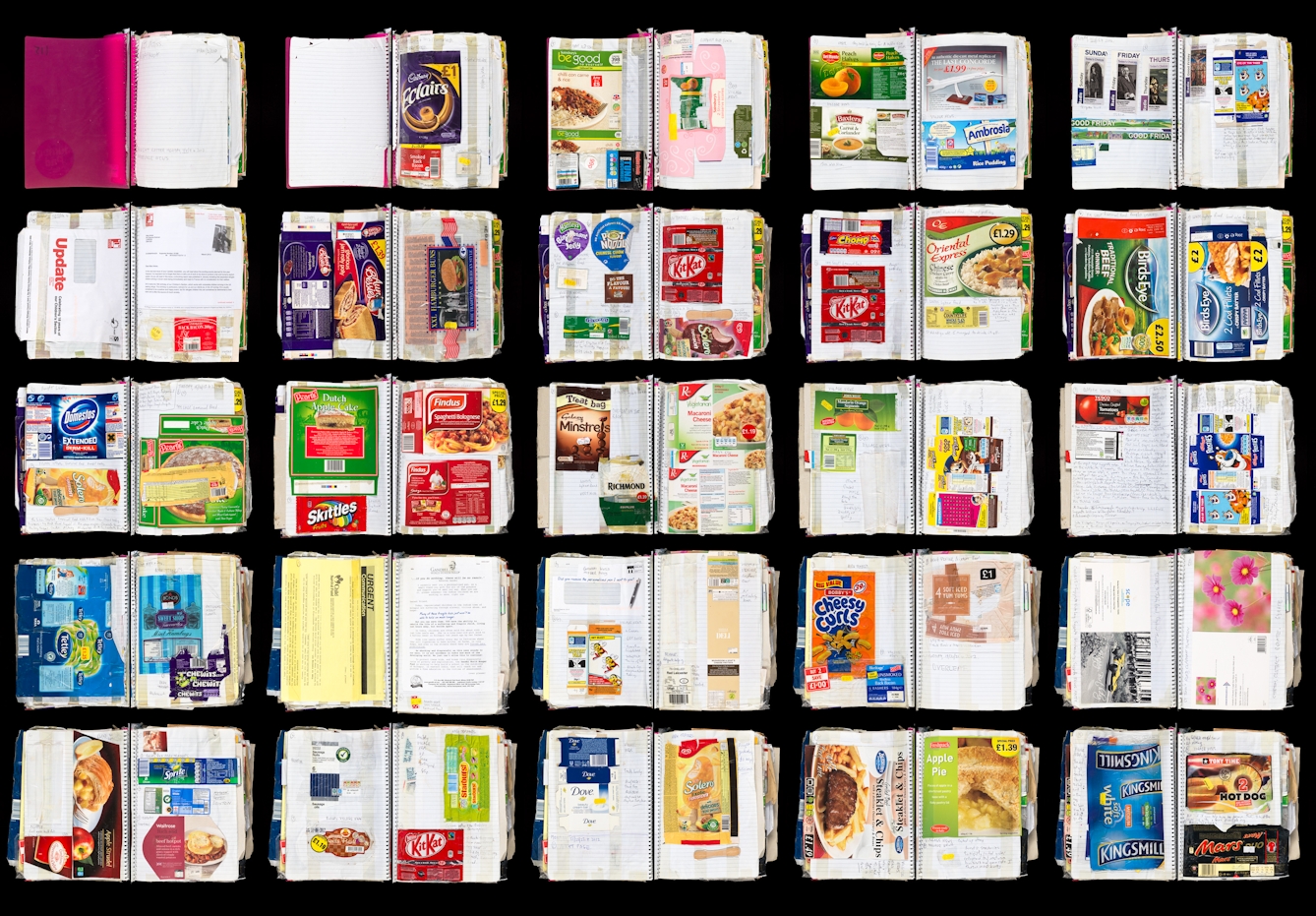

There have been other challenges in digitising the works. Some of the packaging has become unstuck, and Tom has had to decide how to reposition these on the page before photographing. Audrey would often paste down post that was sent to her – but what she was interested in focusing on might not be the same thing we’d be interested in.

Colour chart used during photography to calibrate the camera sensor to the studio lights. This ‘profiling’ of the camera creates a digital representation, which is as accurate and faithful to the original as possible.

The content of the letter was seemingly less of interest to Audrey than the paper it was written on, or the manila envelope it arrived in, which is pasted beside it. Where these items had come loose, we had to decide whether to photograph both sides of the item or only from the side Audrey intended it to be viewed.

Sometimes, Audrey has stapled some of the letters she received in such a way that they can be folded up and read, but some of that information is lost in the fold. Here we had the option to either photograph the fold-outs in situ and accept that some of the text will be hidden or ask Stefania to carefully de-staple the fold-out so the items can be photographed in full. In these instances, we decided it would be better to not interfere with the way Audrey created the volumes and what she chose to be visible.

Frozen in time

As with the cataloguing and conservation work, we wanted to make sure that the digitisation provided an accurate reflection of Audrey’s work and how she wanted things to be seen.

Digitisation means that more people will be able to see Audrey’s work as the images are placed online. It creates a facsimile of how the volumes looked at that moment, before further handling and time age and change the items even further. But digitisation cannot replicate the feeling of physically handling these items, of encountering them as wonderfully physical three-dimensional objects.

PP/AMI/D/220: scrapbook. Composite image of the first 25 openings.

There is an experience in the materiality of these volumes that is as much about touch and smell as it is about what you can see on the page. Digitisation allows another way into exploring the collection, and it means that some of the works will be handled slightly less to ensure their longer-term survival. It’s a balance between allowing as many people as possible to experience Audrey for themselves while also keeping the items safe.

I think back to something Tom mentioned earlier: “We’re creating digital negatives, frozen in time, a time stamp of the manuscripts.” And I think about Audrey recording her life experiences day after day, noting the time she purchased items and cross-referencing to the time on till receipts and bus tickets, making sure she had her own time stamp and record of everything that happened to her.

I remember something I read Audrey saying about her drawings: “My sketches are like milestones in a way, because they fix the temporary into the permanent. Meaning I’ve fixed them once and for all. They may change afterwards, but I’ve recorded them.”

The scrapbook sits open in the darkened photography studio under a camera poised to take a photo. What’s on the page may change afterwards, but we’re recording it. The act of digitising: fixing the temporary into the permanent.

You can explore the Audrey Amiss archive through our online catalogue. To see the archive, you need to join our library and request to view specific items from the collection.

About the contributors

Elena Carter

Elena Carter focuses on developing the collections at Wellcome to challenge the way that we think and feel about health. Elena is particularly interested in radical and social histories and material that gives voice to marginalised groups. As Collections Development Archivist, she works directly with people to find the best home for their materials, with a focus on working collaboratively and ethically.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.