The restrictions resulting from the coronavirus pandemic have given the general public an idea of what daily life is like for many disabled people. Artist and performer Dolly Sen wonders whether the current inhumanity towards disabled people will continue, or if we will step up to campaign for a more equal, caring society.

This has been a strange year. Who would have thought we’d become a mask-wearing people uncertain of the future because a new virus had changed the world?

We are now all urged to socially distance, but some people have been at the wrong end of distancing for years. The public got a taste of the isolation, loss of access to work, leisure and places, and reduced rights and freedoms that some disabled people experience as everyday life. The remoteness of disabled people from dignity, compassion and basic rights is so far away from what humans should be.

I remember some disabled friends saying that maybe now the normal world has gone through a similar experience, we would be able to change the world and society for the better, making it equitable for all.

Some good has come out of this crisis. People have stepped up to help their neighbours with food and prescription collections, and made masks and scrubs for NHS workers, the heroes of 2020. Hundreds of mutual-aid schemes were set up to help those who fell through the cracks. But a few months after the peak of the pandemic, we can see that disabled people have not merely fallen through the cracks, but been plunged into a dark and gaping chasm.

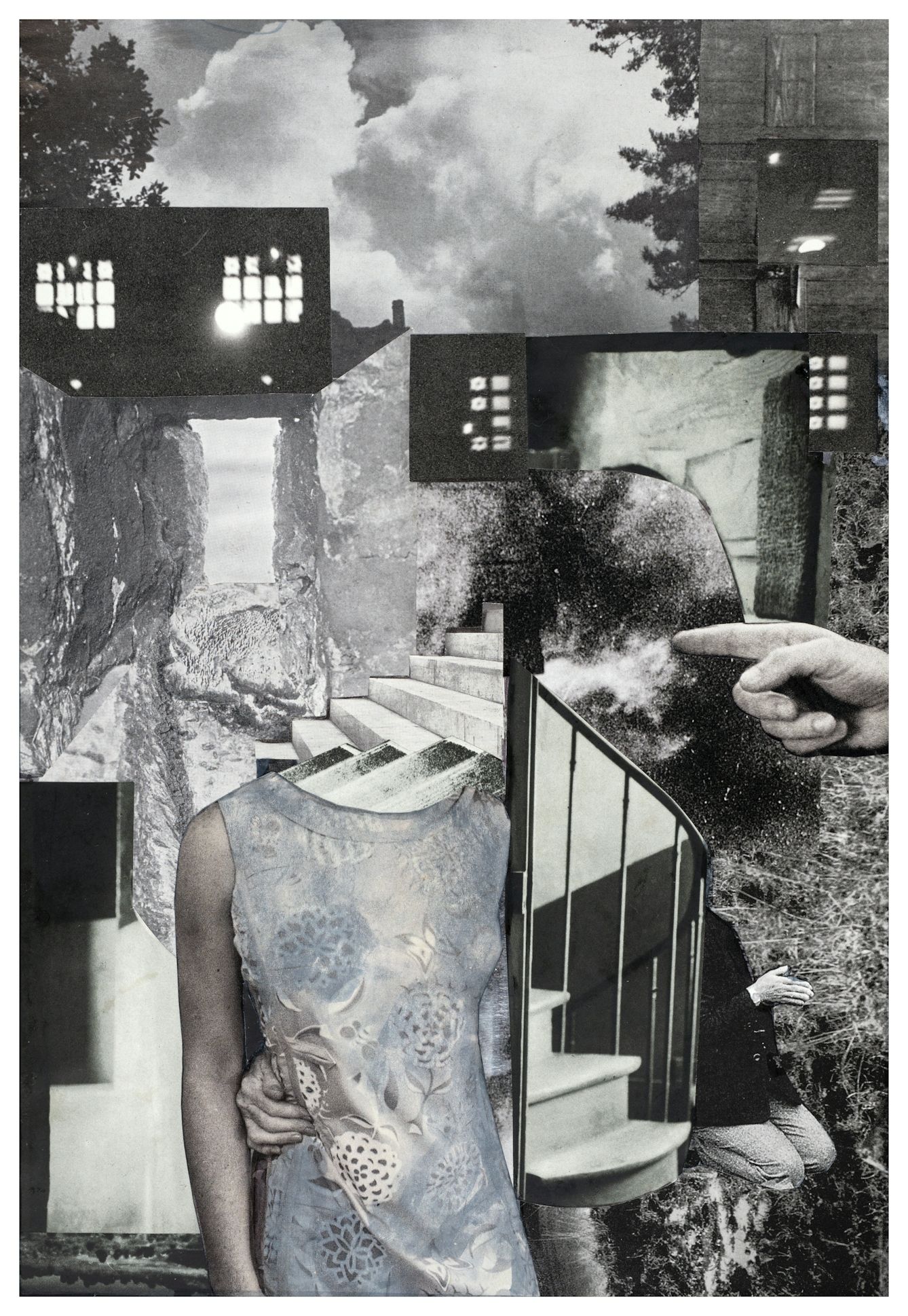

‘Access to affinity: the faceless grace of compliance’ by Pum Dunbar.

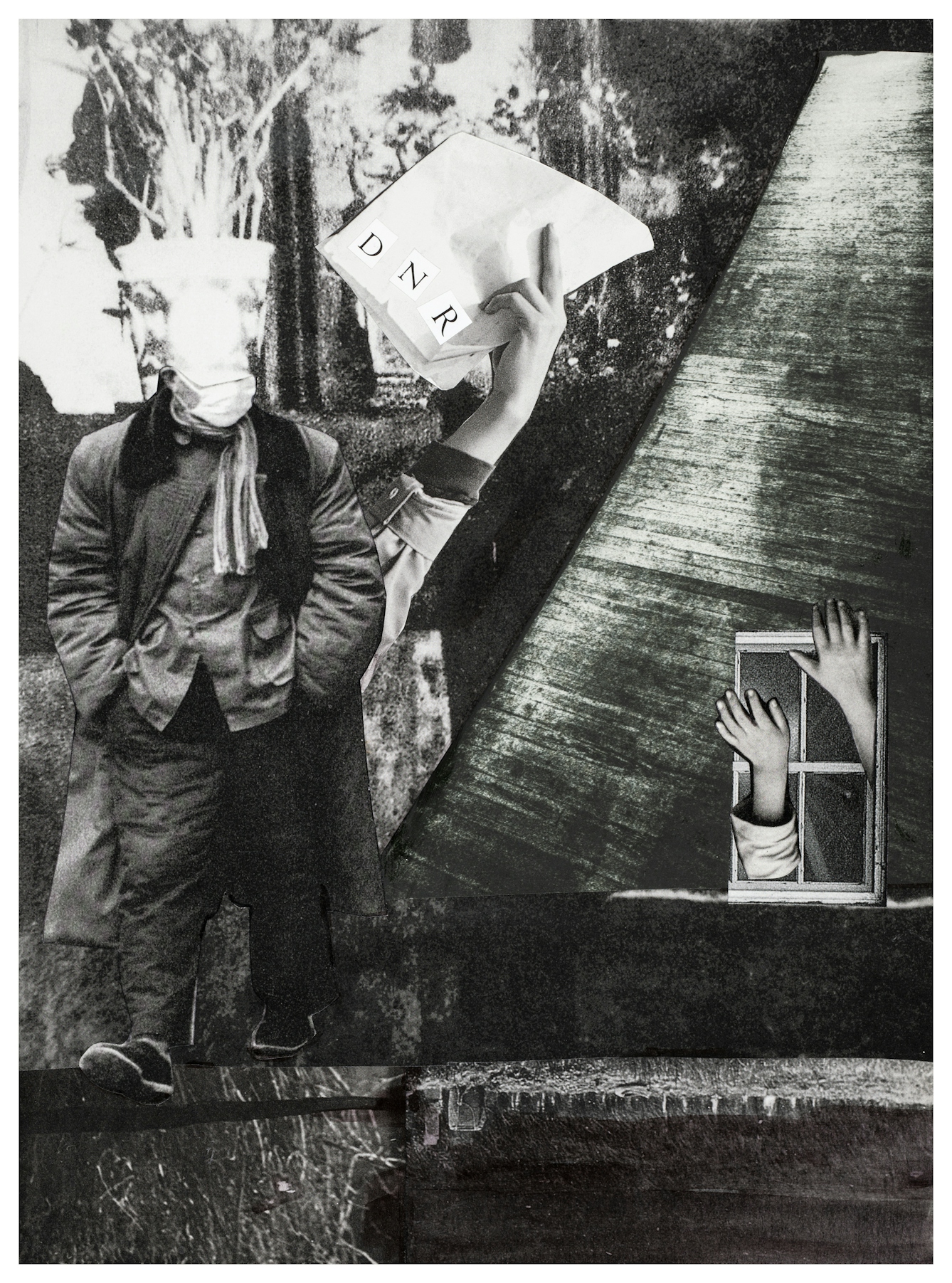

Disabled people are 11 times more likely to die from coronavirus than the rest of the population. You might assume that this is to do with specific medical conditions they have, but this is only part of the story. Far more important is the inequality they experience, stemming from deprivation, disconnection, unsuitable housing, and DNRs turning up in the post instead of helpful information. (A DNR is a ‘do not resuscitate’ document signed by a doctor, which tells your medical team not to attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event of a heart attack.)

The luck of the draw

Some people think the words ‘vulnerable’ and ‘disabled’ are interchangeable, and some think that vulnerability is innate in the disabled person themselves, instead of being caused by a system or process that makes them vulnerable. If you create more barriers and limit access to resources, of course a person is made vulnerable. The list of ways in which the handling of the crisis has negatively impacted disabled people is unhappily long.

One item on that list is the Coronavirus Bill, which has suspended the Care Act, meaning local authorities don’t need to help disabled people and children. Some people are literally stuck in their beds without help. More than 60 per cent of disabled people said they have experienced problems getting food, medicine and other things they need. Even those with care packages have found that their personal assistance and carers were self-isolating or unable to get PPE in time to support them. My disabled partner and I were lucky – we had friends who helped.

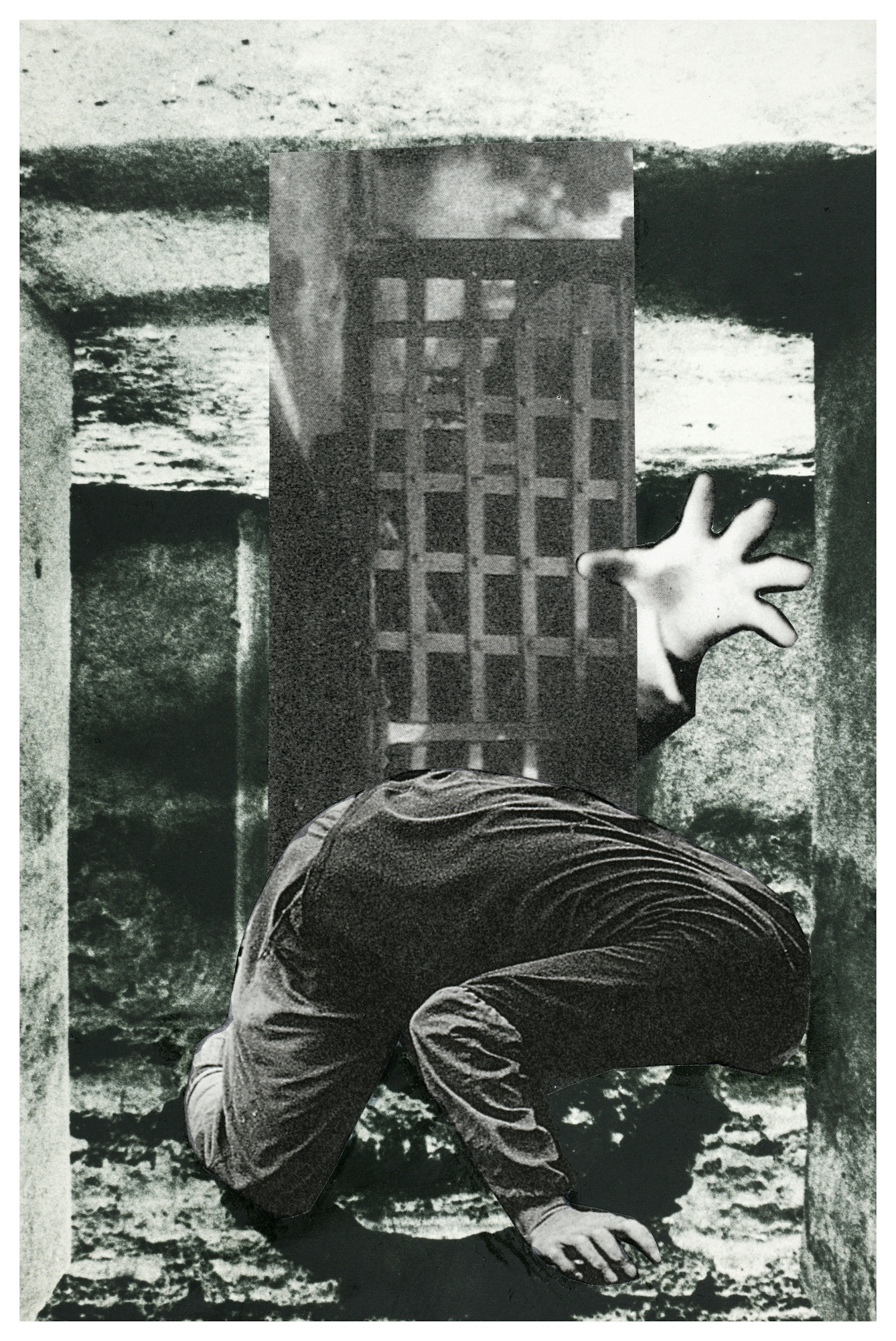

‘Struggle to find the freedom to console’ by Pum Dunbar.

We were told to rely on the internet to find up-to-date information, or to order food. Unfortunately, many disabled people do not have access to the internet. Disabled adults make up a large proportion of adult internet non-users. In 2017, 56 per cent of adult internet non-users were disabled people. It’s not hard to see how disabled people feel abandoned and disregarded by the government.

It is the luck of the draw if social care services are there to support you, or if the community can step up and offer help, such as collecting prescriptions or delivering food boxes. Sometimes our only gift or interaction from society has been a DNR form in the post, to fill out under pressure and without discussion.

If you think we have no worth, you are not looking hard enough.

Some disabled people had no right to their own lives when ventilators were given to the non-disabled, because our health service is underfunded and can’t afford to save everyone. This devastating betrayal has made some people claustrophobic in their loneliness and now mistrustful of the last bastion of the system that they had belief in before: the health service.

How many disabled people will stop going to the doctor, worried the only thing they will be offered is a DNR form? This is not even eugenics by the back door.

I am not against people choosing their own DNR order, or for their family to do that if the person is unable to make the decision for themselves. I recognise that some doctors are in a difficult situation, and only have to do this because of the impact the coronavirus has on our chronically underfunded NHS.

But doctors are also not free from prejudice and assumptions about disabled people. Some assume we are suffering and they will be doing us a favour. Most of disabled people’s distress is their distance from normal life. Now we don’t have a say in whether we can keep on breathing. If you think we have no worth, you are not looking hard enough. You are not looking deep enough into the hearts you want to stop.

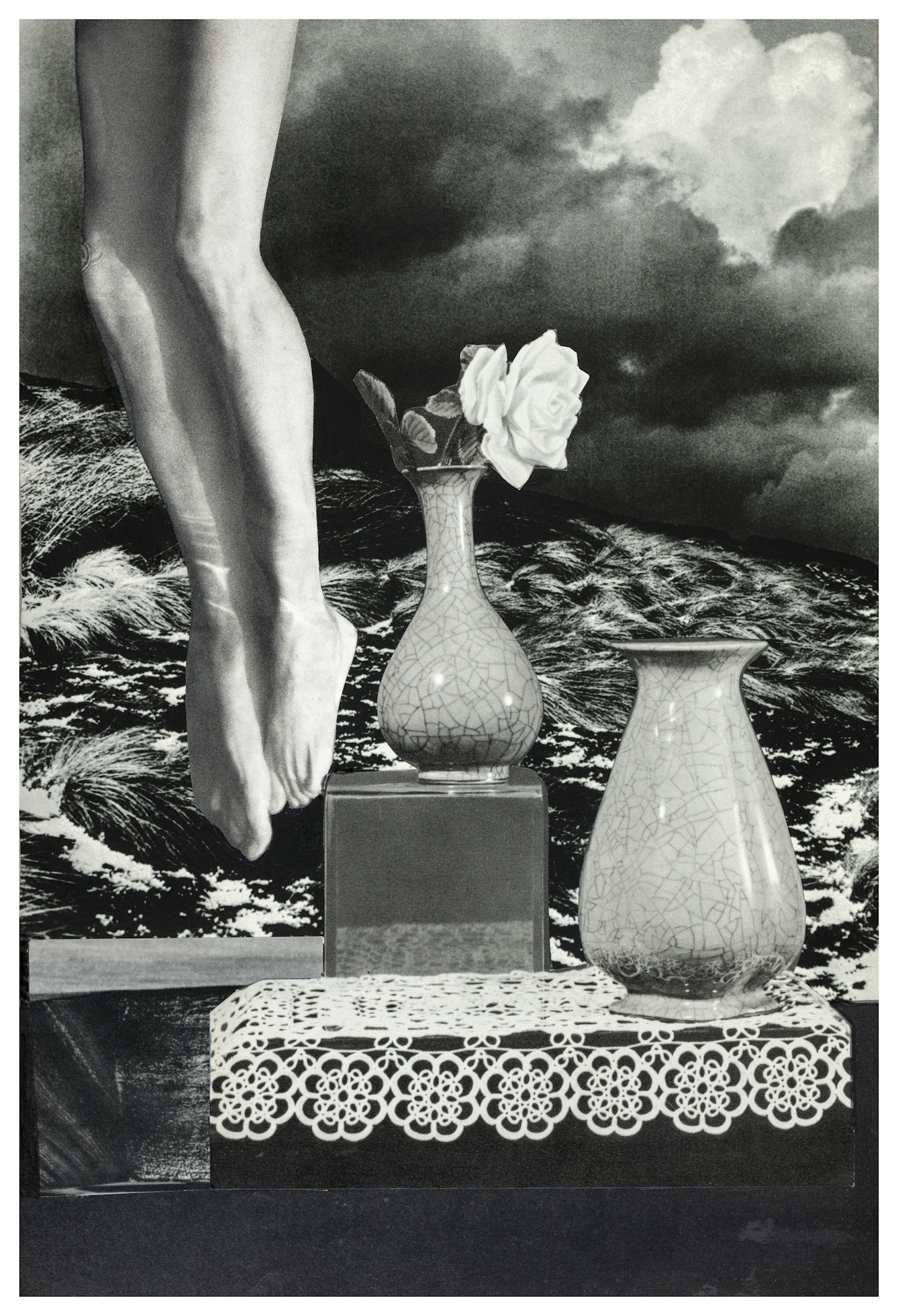

‘The suspended swimmer: still life with the afterlife’, by Pum Dunbar.

Aspire to be a decent human

This pandemic has both highlighted and exacerbated inequalities in our society. We are at a crossroads where we can either address these disparities or watch them become more brutal in the forthcoming recession. Is the inhumanity disabled people faced in 2020 a sign of things to come? Or have lockdown and mutual aid shown people the need for a kinder, more supportive society?

I would love this crisis to have some positive consequences, showing that people have become more empathic and want to do something about the inequities in our society. Humans inhabiting this land in these times can step up into their humanity, as people often have in history, and insist on change.

They can voice their objection at how disabled people are treated in conversation, on social media, in contact with MPs, and in situations where they see discrimination. The ordinary world is a broken world for many disabled people. Supporting the disability civil-rights campaign is a step in the right direction.

Read more

About the contributors

Dolly Sen

Dolly Sen is a writer, speaker, performer, artist and filmmaker. She has been labelled ‘mad’ by a society that has helped to drive her mad. Queer, disabled, person of colour, she is a broken child taped together with glitter and stars. She/they.

Pum Dunbar

Pum is an artist whose creative practice is driven by her fundamental need to make sense in order to cope and grow. Her art-making plays an integral part in her ability to manage her life with autism. Her collage praxis is therefore fundamentally private in its origin. It supports her to process and develop insights into her ideas, feelings and experiences. For Pum the art-making process is the by-product of human organic intelligence; her collages are affective reflections of lived experiences. Her creative praxis is underpinned by practice-led research, a growing understanding of affective neuroscience and a commitment to lifelong learning.