In attempting to explain what happiness is, writer Kate Wilkinson found herself thinking of periods when she’d experienced unhappiness instead. It seems that happiness almost defies definition, endlessly morphing according to time, our stage of life, and our day-to-day experiences.

Happiness in time

Words by Kate Wilkinsonartwork by Laurindo Felicianoaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

In December last year I experienced a bout of insomnia. A couple of nights with practically no sleep left me feeling as if my whole experience had become one incredibly tiring day that wouldn’t end. I otherwise felt fine about my life. But without sleep that didn’t matter; nothing made sense.

This went on for a few weeks, and after lots of the gentle, obvious methods for improving my sleep didn’t work, I imagined violent ways of knocking myself out, putting myself under the warm blanket of unconsciousness, even if that meant self-destruction. It frightened me that even when everything seems to be going well, something basic like a lack of sleep can totally ruin our happiness.

There are two main definitions of happiness, which operate across different timescales: one concerns your moment-to-moment mood; the other reflects a more overarching feeling towards your life and circumstances. The two can’t be completely separated.

Even though I was generally content, during my insomniac days my happiness was fundamentally ruined by my feeling of exhaustion. And in the night, I felt trapped in a restless headspace that made it impossible to be still, my thoughts spiralling around pointlessly, the opposite of contentment.

Happiness is affected by our perception of time, which itself can be influenced by many things, from sleep deprivation to psychedelic drugs, as well as the age we are. Time seems to pass more slowly in childhood and more quickly in older age.

People nearer the beginning of their life generally have a sense of time to come. The old are aware that most of their life is behind them. But things can happen at any age to knock someone out of a ‘normal’ sphere of experience.

“It frightened me that even when everything seems to be going well, something basic like a lack of sleep can totally ruin our happiness.”

In her essay ‘Time Lived, Without Its Flow’, the poet Denise Riley attempts to describe “the curious sense of being pulled right outside of time” following the sudden death of her son. Any sense of futurity or living within sequential time was replaced for her by a strange feeling of “bright emptiness”.

Events and expectations

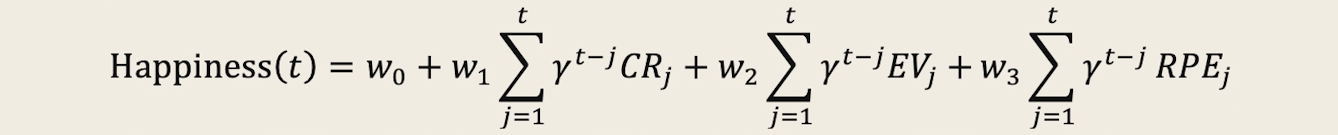

The cognitive and computational neuroscientist Robb Rutledge investigated the moment-to-moment form of happiness, and his lab developed an equation to predict it. This is what they came up with:

It looks confusing, but essentially Rutledge’s team found that momentary happiness “depends not on how well things are going, but whether things are going better than expected”. Their study involved thousands of people taking part in various luck-based games and reporting on their happiness at different points.

Whether they won the game or not wasn’t so important in predicting their happiness: what mattered most was whether they did better or worse than they thought they would. The research shows that our expectations affect our happiness as much as actual life events.

Happiness is often framed as our central goal in life, though it’s mostly where you aren’t – it’s back then or over there.

”The moment is in flux and so are our minds, moving with the ever-changing present, projecting forward and back as the seconds tick by.”

The findings feel intuitive to me, but they point to something I hadn’t considered. I had thought of the overarching sense of happiness as the more reflective type and the momentary happiness as the more spontaneous, living-in-the-moment type. However, Rutledge’s equation frames even this second form of happiness in terms of expectation, a prediction into the future, even if it’s just by the few seconds it takes to flip a coin or text a friend.

But we are never fully still, fully in the moment – the moment is in flux and so are our minds, moving with the ever-changing present, projecting forward and back as the seconds tick by.

I often don’t realise what my expectations have been until I feel pleased or disappointed, and I realise that I must have either been hoping for a better outcome or predicting a much worse one. When my expectations are low, or non-existent, there’s normally a better chance that I’ll feel good.

But I don’t think the answer to happiness is to always have low expectations. Expecting the worst all the time can easily lead to a negative mindset and, in any case, the expectation of a positive outcome is often what motivates me to do the things that could make me happy in the first place!

Trying to pin down happiness

Expectations themselves are often based on an aggregation of experiences: the last time I tripped over, I fell on my face, so this time the same is likely to happen (maybe I’ll put my hands out). I performed really well in my exams in school: maybe I’ll perform well in my job. My parents own a house: maybe when I’m their age I’ll own one too. No one I know is a lawyer: maybe that profession isn’t for me.

Our expectations can shift over time and are also moulded by wider forces than direct experience. The stories we read and watch give us ideas about what life should look and feel like at different ages, and of course can create stereotypes.

“People nearer the beginning of their life generally have a sense of time to come. The old are aware that most of their life is behind them.”

When James Marriott of The Times wrote about the intense emotions of being young, fellow columnist David Aaronovitch wrote a piece in response about how his experiences of middle age have been far more emotionally poignant. Many on Twitter objected to the generalisations each piece necessarily made – especially Aaronovitch’s assertion that the young can’t know the deepest emotions.

Relating to other people’s experiences, in fact or fiction, can be reassuring, but no one likes to feel that their life is following a predetermined path. An image that occasionally comes to me during periods of low mood is that of a computer running code, one line leading to the next until finished.

Everything seems to be a foregone conclusion, and this negative feeling stops me from appreciating how unpredictable life can be, with all its possibilities, good and bad. Expectations have taken over, but they’ve also disappeared. I can barely imagine anything happening in the future, but I am also certain that whatever does happen won’t be particularly exciting.

Fortunately, I haven’t felt like that in a while. In happier moods, I’m often planning little schemes for the future, whether that’s meet-ups with friends or browsing rescue cats online.

Happiness is often framed as our central goal in life, though it’s mostly where you aren’t – it’s back then or over there. It’s easier to identify times of happiness after the event; if we stopped to question whether we were happy in the moment, we would risk bursting the bubble. The slippery nature of happiness makes it hard to write about directly – here I’ve used two personal anecdotes about misery rather than happiness.

But happiness takes many forms as we pass through life’s stages. It seeps in at different moments, whether expected or not. In the attempt to pin down happiness, capture it in photos, or even just define what it means, the emotion slips away. Rather than being a static ideal, it’s something we can only experience as we live through time.

About the contributors

Kate Wilkinson

Kate works at Pushkin Press. When not submerged in a book, she can be found walking or practising Spanish. Sometimes both at once.

Laurindo Feliciano

Laurindo Feliciano is a Brazilian contemporary artist and illustrator who has been living and working in France since 2003. Inspired by vintage aesthetics, he creates illustrations using techniques such as collage and digital painting. All his illustrations and posters share a certain nostalgic flair and a great passion for surrealism. His work has been published and exhibited in several countries, and in 2014 he won the AOI (Association of Illustrators) Professional Editorial Award. Among his clients and collaborations are the Musée des Arts Décoratifs/Paris, the V&A, British Airways, WIRED, the Financial Times, Penguin Vintage, Netflix, and many others.