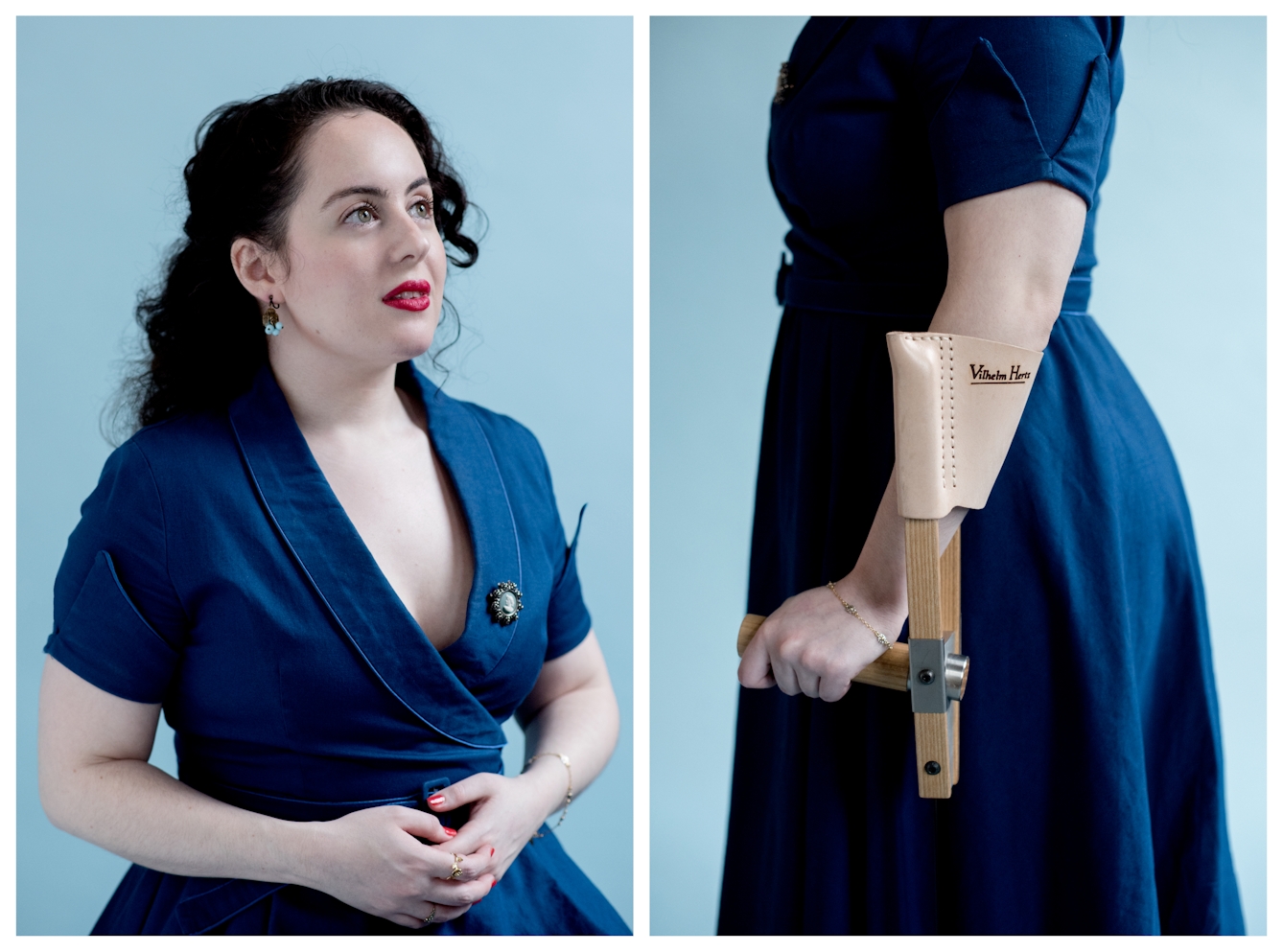

As a child, Natasha Lipman thought her body was simply ‘weird’. An unexpected diagnosis when she was a young adult provided a lot of answers – but the stigma around disability meant she still wasn’t getting the help she needed. Then she tried a wheelchair.

How my wheelchair changed my life

Words by Natasha Lipmanphotography by Camilla Greenwellaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

My whole life had been marked by pain that I never had a name for. My family and I always thought that I just had a bit of a ‘weird body’.

I experienced dislocations, subluxations, slipped disks, and a whole bunch of other acute injuries that found me in and out of physiotherapy for most of my young life – with no doctor ever suggesting that there could be a systemic cause beyond being double-jointed.

A fluke diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), and tears of validation, came thanks to a new physiotherapist who had been on a course about EDS and referred me to a specialist. I finally had a name and an explanation for those things that I could never really understand.

Far from being upset, I was overwhelmed with how many pieces seemed to fit together. I hadn’t even considered looking for a diagnosis, as I didn’t even know that the condition existed. The diagnosis offered me hope that with a name, I would now be able to access the help I needed.

That hope was short-lived, as I realised the specialist physiotherapy wasn’t helping me. With my pain increasing, I started to feel hopeless, and scared of losing my mobility.

“I’d always been disabled; I just hadn’t known the word applied to me.”

The stigma of invisible disabilities

I was in my early twenties, pushing my body as far as I could to try and keep up with my peers, and terrified of getting worse. To me, the worst-case scenario was represented by the idea that I would need to start using a wheelchair.

When I brought this fear up to my physiotherapist, she told me something that would stick with me for years: “You’re too stubborn to end up in a wheelchair.”

I was repeatedly told by my physiotherapist that if I put in the work (which often meant moving for the sake of moving, even when practising the exercises I was given, or simply walking, resulted in injury), and tried hard enough, I would then be able to halt the physical decline that had marked my entire life. This made me believe that I had to keep pushing through the pain, no matter the cost. I believed if I ended up using a wheelchair, it would mark me as a failure – someone who hadn’t worked hard enough to avoid disability.

What I didn’t know then was that I’d always been disabled; I just hadn’t known the word applied to me.

There’s still stigma attached to invisibly disabled, part-time wheelchair users – and many of us with long-term chronic illnesses, especially young people, are told by medical professionals about the importance of limiting our use of mobility aids. In some ways it makes sense: for many conditions, avoiding deconditioning (the loss of strength and endurance) can play an important role in management. It does for me. But many people are unable to access the level of care they need to be able to do this safely and consistently.

I was never told that mobility aids can also be preventative, and that people with a variety of disabilities use them, part- or full-time, for a myriad of reasons.

“When I got my wheelchair, I was able to get shoes that I loved.”

Saying yes to a wheelchair

I’d always accepted that I needed to use crutches to recover from an acute injury, or when my knee pain made walking harder, so why could I not do the same with a wheelchair if it meant that it enabled me to leave the house? Like many people with invisible disabilities, I didn’t feel ‘disabled enough’ to ‘deserve’ a wheelchair, based on the images of disability I grew up seeing. I firmly believed that I had to just ‘suck it up’ and keep pushing through.

I forced myself to move because I thought that I should, but over time that only increased my pain and fatigue as I pushed myself more than my body could handle. My life became smaller as I retreated from the outside world, impacting my ability to look after myself, work and have a social life.

My mum has always been the driving force encouraging me to use a wheelchair . For her, if something can help improve your quality of life, why not use it? But even as I became increasingly confined to the four walls of my bedroom, I still struggled with the idea of using a wheelchair.

Like many people with invisible disabilities, I didn’t feel ‘disabled enough’ to ‘deserve’ a wheelchair, based on the images of disability I grew up seeing.

"I firmly believed that I had to just ‘suck it up’ and keep pushing through."

But, over time, certain experiences made me more receptive about using a wheelchair. It started with wheelchairs at airports after dislocations – which was a revelation. Then, I started to use my grandma’s old manual chair more often, which enabled me to go out to a shopping centre, for a meal with my family and even to a museum without additional pain and fatigue. It made an incredible difference, even when it was just my mum plonking me down for a walk around the block when I was most unwell.

I had to confront my own prejudices and misconceptions about disability and wheelchairs over the years. Alongside my mum’s encouragement, I am extremely grateful to the amazing activists on social media for the work they do educating people on so many aspects of disability.

My confidence about using wheelchairs was steadily burgeoning. But being pushed in a manual chair was something that left me wholly dependent on other people, as I’m not able to self-propel. While a chair provided me with opportunities to go out, I still felt like I had little independence. Often I couldn’t even control where I looked when we were out.

I spoke to my GP about accessing an electric wheelchair and was referred to the NHS wheelchair services. After a prolonged waiting time for a response, I received a letter, telling me that I wouldn’t even qualify for an assessment as I could get around my home without a wheelchair.

This was disheartening, and I know many others with fluctuating conditions like mine who have experienced similar disappointments. Being able to go out without pain and fatigue should be a valid reason for someone to use a chair, even if they don’t require one at home. After that, I gave up on the idea.

“The “please offer me a seat” badges remind people not all disabilities are visible. This badge is a charity collaboration between me and @misstheabella."

Life with wheels

In 2017, I started a new job and my thoughts returned to getting a chair of my own. Walking around a large office, even a few hours a week, caused significant pain and fatigue that took nearly a week to recover from.

I was lucky to get help from my family to self-fund for a power chair, but this is a privilege many people do not have, who are unable to access a mobility aid that could drastically improve their quality of life.

Making the decision to use a power chair changed my life. My chair has enabled me to use my energy for my work and to rebuild my strength safely, instead of forcing my body to move in ways that could be harmful. It drastically cut down on the severity of my symptoms, in some cases knocking off days from my recovery times. It opened the world to me again and has touched my life in so many ways.

I understand how confusing it can be for people who don’t understand fluctuating, invisible illnesses to see part-time wheelchair users who may be able to get up from their chair in public. However, the constant feeling that we need to justify our disability (especially to strangers) can be exhausting. Which is why it has been heartening to see greater public awareness of invisible disabilities through “please offer me a seat” badges and signs on trains and public toilets that remind customers “not all disabilities are visible”.

I’ve now been a wheelchair user for nearly two years, and it’s the small, everyday things I gave up long ago – like being able to pop to the shop to pick up food for myself – that mean the most to me. I don’t need my chair every day, but the difference it has made to my quality of life is dramatic. It is there to help me when I need it. I only wish I’d known a decade ago that it was an option.

About the contributors

Natasha Lipman

Natasha Lipman is a chronic illness blogger and part-time journalist from London. On her blog, you can find her interviewing people who are doing amazing things in the disability space, exploring inclusive fashion and working with experts to create practical advice about living with chronic illness. You can also find her on Instagram and Twitter.

Camilla Greenwell

Camilla Greenwell is a photographer specialising in dance, performance and portraiture. She regularly works with Sadler’s Wells, Barbican, Candoco, Rambert, The Place, the Guardian, the British Red Cross, Art on the Underground and Wellcome Collection.