One unexpected side-effect of menopause, for some women, is feeling less visible. Maybe this is because menopause is still a taboo subject, but Helen Foster suggests that it has more do with how society viewed middle-aged women in the past, and how this has influenced the way that they are treated now.

Invisibility

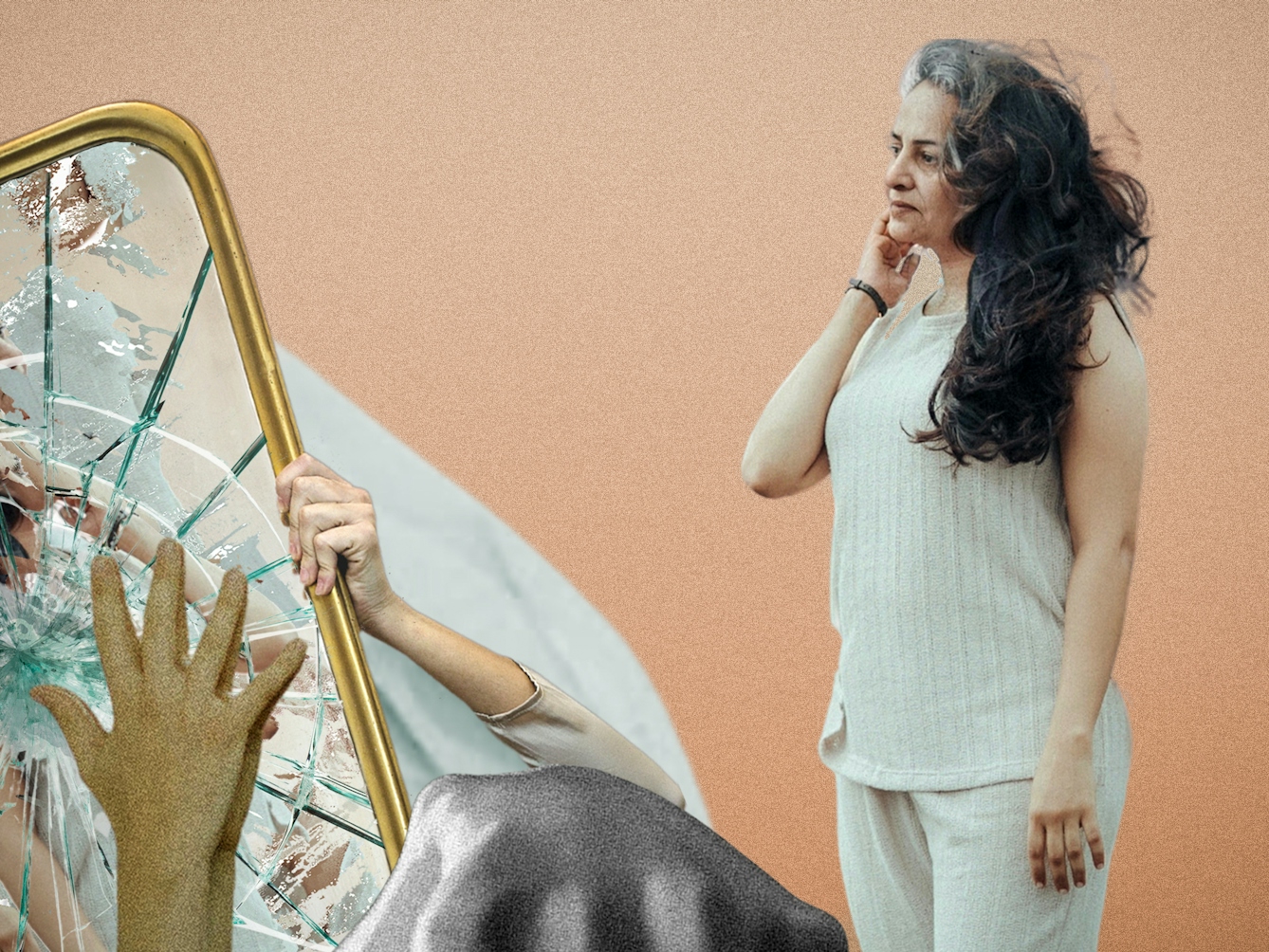

Words by Helen FosterEast Midlands Oral History Archiveartwork by Asma Istwaniaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Article

- Serial

Many women who reach midlife and menopause report feeling that they have become invisible. Many, like Claire, feel frustrated at being silenced and sidelined as they grow older. As Claire says, “I’ve got a voice that deserves to be listened to.”

Dubbed “invisible woman syndrome”, this phenomenon describes how women in their 40s and 50s, typically the age that most women experience menopause, find themselves overlooked in social situations, in the workplace and in the media. Melanie Joosten, a researcher from the National Ageing Research Institute in Australia, summed up the gender imbalance in attitudes towards ageing: men become more highly respected, whereas women become less relevant. This phenomenon can have significant consequences, not least in the workplace.

Working while menopausal

Although attitudes are changing, there is still a lack of recognition of how women’s experiences at menopause can impact on their working lives. In July 2022 the parliamentary Women and Equalities Committee report ‘Menopause and the Workplace’ noted that “Women of menopausal age are the fastest growing group in the workforce… Yet these experienced and skilled role models often receive little support with menopause symptoms. As a result, some cut back their hours or responsibilities. Others leave work altogether.” Despite this recognition of the struggles of menopausal women, in 2023 the British government rejected the report’s recommendation to introduce mandatory menopause training for general practitioners.

A lack of support causes menopausal women to disappear from the workforce.

A hidden history

It can be argued that at the heart of the historical record lies a gender bias – Western history has traditionally been written by men. Delve into any of the many archives across the country and you are likely to find a distinct lack of stories about women in this life stage. As a result, our understanding of how menopause was experienced in the past is, at best, hazy.

Another possible reason for the absence of menopausal accounts from history is the fact that there were fewer women of menopausal age, although there is enough historical evidence to show that plenty of women did live well past menopause. Childbirth and disease were particularly dangerous, and many women died before they reached menopause.

According to the UK Office of National Statistics, in 1841 the average lifespan of a female was 42.3 years and by 1891 it was 47.8 years. Life expectancy for women in the UK today is around 82 years, meaning many more menstruating females are likely to experience menopause, something that might make the medical and political establishment take more notice.

Absent healthcare

Historically, menopause has largely been overlooked by the male-dominated medical establishment. Until well into the 19th century, male physicians rarely entered the female sphere of “women’s problems”, and women usually dealt with them using home remedies and superstition. The intimate nature of menopause continues to be a reason why it’s something we reference in whispered, often outdated euphemisms – or we just don’t talk about it at all.

Experiences of menopause are largely absent from medical archives.

Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098–1179) was a rare female voice speaking about women’s health. She was a German Benedictine abbess, a writer and composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, medical writer and practitioner, and one of very few women published in early medieval Europe. Hildegarde spent her life, from the age of eight until her death, living in convents at close quarters with other women, giving her an opportunity to intimately observe the whole female life course.

Her scientific and medical works are considered relatively reliable for the times in which she lived and she was certainly aware of menopause and wrote about it. In ‘Causae et curae’ (‘Causes and Cures’), she talks about the ceasing of menses in women and recommends holistic herbal remedies.

The illusion of youth

Novelist Ursula Le Guin described menopause as “probably the least glamorous topic imaginable”. Women of menopausal age may feel less appreciated and this view is exacerbated by the focus on youth in our society. The importance of looking and staying young fuels multimillion-pound beauty and cosmetic-surgery industries, which promise that growing older doesn’t have to equate looking older.

But for Lina, growing older shouldn’t be about “preserving your youth” but about “valuing your wisdom”.

Perhaps youth is so prized for women because it’s a measure of female fertility and this was traditionally the primary function of females in a patriarchal society. Across many centuries and in many cultures, motherhood was thought to be the pinnacle of female achievement. Women who could no longer reproduce were thought to have lost their value and could be easily marginalised or discarded. Fertility was never the primary measure of value for men.

Women can’t afford to grow older in a society that values youth over female experience.

Invisibility as a superpower

For some women, invisibility means a release from the expectations of youth and the pressure to attract a mate, and they no longer feel they have to be “on show”. They consider the invisibility that comes with being menopausal and an older woman as a superpower, giving them the ability to act without being judged or to simply not to care about being judged. As Clare says, “the whole invisible woman thing is actually a little bit liberating”.

In her book ‘The Meanings of Menopause’, Ruth Formanek suggests that this crucial life stage requires “a dismantling of the old and a building of the new”. She considers it a time for the “redefinition of self”. Rather than being resigned to fading into the background or disappearing from the workplace and public life, menopause can be a time for women to make life changes on their own terms and to embrace invisibility as a release from the confines of youth.

About the contributors

Helen Foster

Dr Helen Foster is a writer and oral historian currently based at the East Midlands Oral History Archive at the University of Leicester. She has a particular interest in narratives around life stages and, as well as menopause, her work has explored childlessness and bereavement. As a poetry-therapy practitioner she facilitates workshops for people living with mental health challenges, using writing as a therapeutic tool. She is currently co-authoring a book on creative writing and health for Emerald Press.

East Midlands Oral History Archive

The audio extracts used in the series ‘A Bloody History of Menopause’ come from interviews, conversations and audio diaries about lived experiences of menopause recorded for the Silent Archive project. The project was led by the East Midlands Oral History Archive at the University of Leicester (from 2020–22) and funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Asma Istwani

Asma is an artist and arts producer from London. She has worked with several organisations and brands, including Tate, Somerset House and Jo Malone London on a variety of creative projects. Through her collages she aims to make relatable statements about the experience and racial and sexual depiction of ‘othered’ women, with special interest in those who, like herself, make up the SWANA (South West Asian/ North African) diaspora. Asma is also the founder of RIOT SOUP, an art collective and community for Black and Brown women artists in London.