Rick Burgess coped with the death of his mother in February 2020 by immersing himself in the task of protecting local Disabled communities from Covid-19 with practical aid and through political pressure. He has witnessed a growing anger about the government's apparent failure to protect and support at-risk groups because of an insidious belief that these groups don't contribute to society and are therefore expendable.

Society, not Covid-19, makes us vulnerable

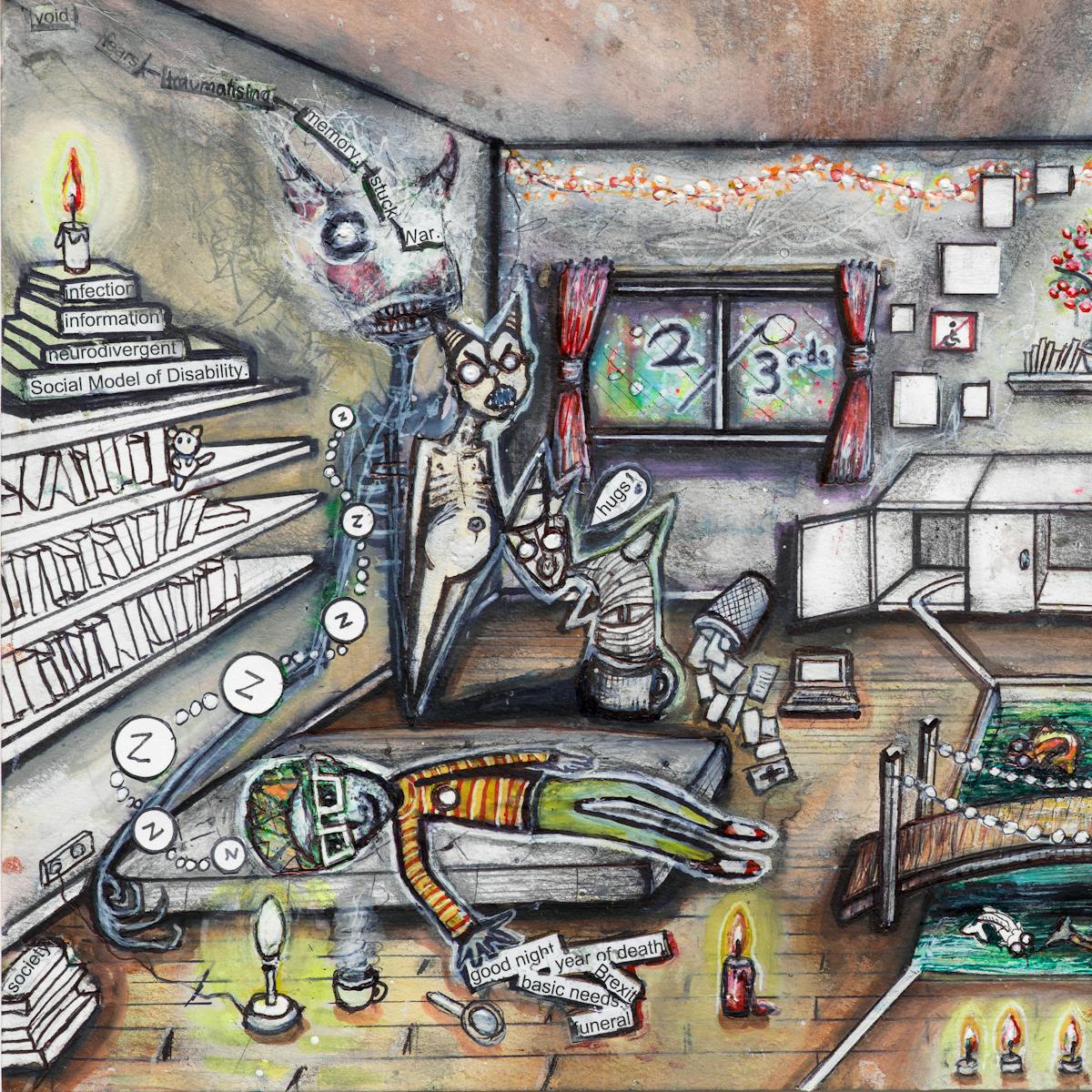

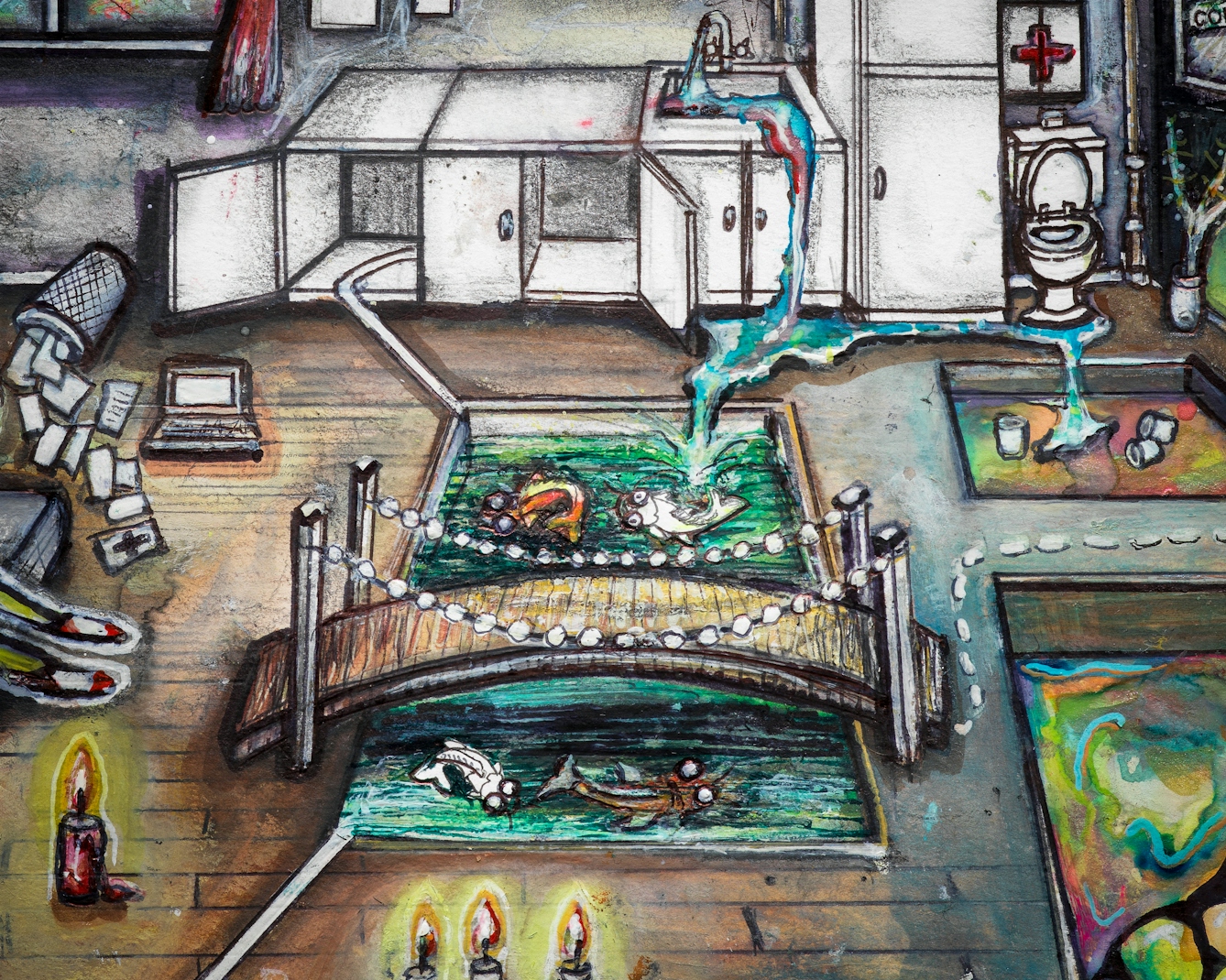

Words by Rick Burgessartwork by Carrie Ravenscroftaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

Before 2020 became infamous, it was already a monster to me. For years I had been a full-time carer to my mum but, as her condition deteriorated, she needed 24-hour care, so we looked for a care home where she would feel comfortable. Miraculously, we found one.

In January 2020 she suffered a terrible fall and fractured her pelvis. This meant an over-long hospital stay, which was not good for her. I helped get her back into the familiar surroundings of her care home, and installed new, adapted equipment to make life easier. Seeing her in a hoist was both sad and a little comic: she was tiny and frail, but still Mum.

Soon after settling her back in the home, I received a call one morning at 06.00 telling me my mum could not breathe, and I should get there fast. I sat with her for her last 24 hours. Early on 17 February, my mum left planet Earth.

Her two cousins were rocks. They helped organise the overly formal funeral to satisfy traditionalist family members, and collected her clothes, shoes and all the other evidence of a life. We said our final goodbyes on 9 March and, as well as failing not to cry, I threw in a joke about toilet rolls and hand sanitiser.

One step ahead of lockdown

To fill the hole left by Mum’s passing, I immersed myself in work. I have life-long mental health issues, and energy and physical mobility impairments. The day after the funeral, I kept myself busy, devouring as much reliable information (largely not UK-based) on Covid-19 as possible. I was shocked by what I found.

I immediately rang my workplace: “We need to cancel next week’s public event… we need to discuss moving from working in the office to working at home – and quickly.” By the end of that day, we at the Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People (GMCDP) had transitioned to home working. Ten days later the government implemented lockdown. Many Disabled people are better informed and act more quickly than those in charge.

“I received a call one morning at 06.00 telling me my mum could not breathe, and I should get there fast. I sat with her for her last 24 hours. Early on 17 February, my mum left planet Earth.”

My job at the coalition is to help run the GM Disabled People’s Panel, a unique, pioneering experiment in helping regional power work with Disabled people to improve things. For a while, it was all hands on deck. I did a few runs distributing food and personal protective equipment (PPE) to our coalition members.

We moved rapidly from monthly to weekly Zoom meetings, gathering and sharing information, identifying problems as they occurred and bringing them to the attention of the authorities.

Shockingly, it began to emerge that the care sector was used as a kind of pressure valve to prevent NHS hospitals being overrun. Thousands of elderly residents were shut away in care homes, allowed to infect others and die themselves, often with family unable to visit.

As we fed our findings into the coordinated regional response, we hoped our expertise would enable the system to respond better to Disabled people’s needs. We ran what was then the most comprehensive survey of Disabled people’s experiences during the pandemic. In addition, we briefed various groups, which led to our involvement at a national level, with the Cabinet Disability Unit.

The magnifying lens of Covid

As my colleagues and I battle with the second wave, the magnifying lens of Covid is making the pre-existing crisis even starker. Our fragmented public health system cannot cope with a pandemic, which desperately requires a joined-up response, not multiple competing trusts and commissioning groups. (There are 12 top-level health organisations covering my region alone.) And as the NHS has been broken up into smaller businesses to enable privatisation, effective systems of coordination have been eroded, making command and control a real challenge.

“The ongoing profiteering from PPE and the failing test and trace system is having a demoralising effect in my community, where food banks and charity are now a standard part of how people stay alive.”

While nationally only a third of care homes are getting the PPE they need (and were promised), locally, my colleagues and I are witnessing worrying shortages of equipment. One Disabled woman I know of, who should have had a new component for her breathing system replaced daily, has had to re-sterilise and reuse it for months.

The ongoing profiteering from PPE and the failing test and trace system is having a demoralising effect in my community, where food banks and charity are now a standard part of how people stay alive. Reports of billions in public money flowing to corporate cronies while desperate people caught out by the pandemic receive less funding only add to the despair.

We are not vulnerable because of Covid

The repeated use of the term ‘vulnerable’ is emblematic of this culture: no one is inherently ‘vulnerable’; rather, society chooses to make them ‘vulnerable’ by failing to provide adequate support. To label someone at risk as ‘vulnerable’ focuses on the individual as the problem – an insidious form of victim blaming.

I felt even more of an outsider when a group of scientists recently proposed that ‘vulnerable’ people should barricade ourselves in our homes for the foreseeable future so that commerce could continue as normal. I felt it was outrageous to suggest we should jettison any illusion that we were part of society, and was convinced that it would not work in practice, for nobody lives in isolation.

When will society acknowledge that millions of us make hugely valuable contributions to our communities every single day?

We, the ‘vulnerable’, all have family, friends, personal assistants and carers, who all have their own social circles (unless the idea was to literally put us in solitary confinement?). This ill proposition left a lot of us angry, anxious and plotting extreme defiance!

This mainstream narrative of hiding ‘vulnerable’ people away while society returns to ‘normal’ reflects a deeply held bias that Disabled people can’t and don’t work. The assumption that the economy would simply rebound if ‘high-risk’ people were quarantined at home implies that only ‘low-risk’ people are able to be ‘productive’ – a profoundly ableist perception.

The reality is that eight million adults in the UK are carers, and at least 27 per cent of carers are Disabled. When will society acknowledge that millions of us make hugely valuable contributions to our communities every single day?

A zero-Covid strategy

We know from the data, and our lived experience, that marginalised groups have been disproportionately affected by the virus. Disabled people made up two thirds of deaths during the first wave, while making up only a fifth of the population. When the Office of National Statistics released this information, little effort went into publicising it, so it largely went unnoticed in our media, much like the data showing a high risk of death to people of colour and people in poverty.

This shocking state of affairs confirms what the Independent Sage Group and others have been saying: that the only way to address the virus – while not amplifying existing inequalities – is to employ a zero-Covid strategy, which aims to reduce community transmission to zero until the virus is no longer a threat, and relies on an effective test, trace, isolate and support system. Sadly there is little sign our government will do this.

Maintaining connections in an epidemic

The virus has shown how interconnected we are, and that it could not have spread so quickly across the planet if it weren’t for the fact that we humans are highly sociable beings who crave relationship. It is starkly clear that the political vision that denies this reality of human interdependency, and sees us all as “individual market” actors (and Disabled people as ‘lesser’), is incapable of responding to this pandemic appropriately. And that depressing fact is why we have the most deaths in Europe and one of the highest deaths per capita globally.

A bleakness has pervaded me in this year of death, and being busy with work can only fill so much of that void. I have not touched another human being since hugs at the funeral in March. A dear friend who I care deeply for lives in London and has had to shield since the first lockdown. In August I drove directly to her and spent a long weekend, at minimum risk, in search of human contact.

“I hope we realise that no one is ‘vulnerable’ or ‘expendable’ if we place enough value on nurturing and respecting each other’s needs.”

I anticipate that the coming months will be enormously tough, not least as shortages due to Brexit are predicted to hit in the new year. As a movement, Disabled people have endured a great deal and we will get through this, but it will be in spite of our political leadership, not because of it.

I hope this pandemic leaves us wiser, with the understanding that we all depend on each other and on the environment we live in. I hope we realise that no one is ‘vulnerable’ or ‘expendable’ if we place enough value on nurturing and respecting each other’s needs. Or we could, instead, take the coronavirus as a role model, and ruthlessly pursue our individual self-interest. Our choice: human or virus? What are we going to be?

About the contributors

Rick Burgess

Rick Burgess is a Disabled service avoider, a former carer, and works for a pioneering disabled people's organisation (100 per cent managed and staffed by Disabled people) in Greater Manchester. He is also an activist with Disabled People Against Cuts and Recovery In The Bin, among others. In his spare time he enjoys sleep and dusting off his fine art background.

Carrie Ravenscroft

Carrie is a queer and neurodivergent artist from London. Her art practice focuses on women’s health, late diagnosis and the mind-body connection, which she communicates through colour, characters and symbolism in detailed, linked artworks. Recent creative projects include a neuroart exhibition in collaboration with neuroscientists at the Kings College ADHD Research Lab. Outside of making art, Carrie is a a mental health support worker and art psychotherapist at Mind, the mental health charity, and volunteers as a psychedelic first aider with the charity PsyCare.