Chaplain Emma Percy finds strength in the capacity for seeking joy. Spiritual joy, she suggests, comes from faith in the benevolence of God, and like Pollyanna in the classic children’s book, finding reasons to rejoice, even in the face of adversity, has much to recommend it.

Spiritual joy

Words by Dr Emma Percyartwork by Jem Clancyaverage reading time 4 minutes

- Article

In religious practice the constant reminder to rejoice in the goodness of God opens the believer to joy. This becomes a discipline, a virtue and a habit of mind.

Pollyanna’s Glad Game

According to Pollyanna’s minister father in the classic 1913 book by Eleanor Porter, there are 800 rejoicing texts in the Bible; verses that tells us to rejoice, be glad, shout for joy. We are told that he knew this because when he was close to despair, he counted them.

Before he died, he taught his daughter a way of being resilient in a life without her mother, full of deprivation. Pollyanna learned to play the ‘Glad Game’; to actively look for joy, a reason to rejoice, even in tough times.

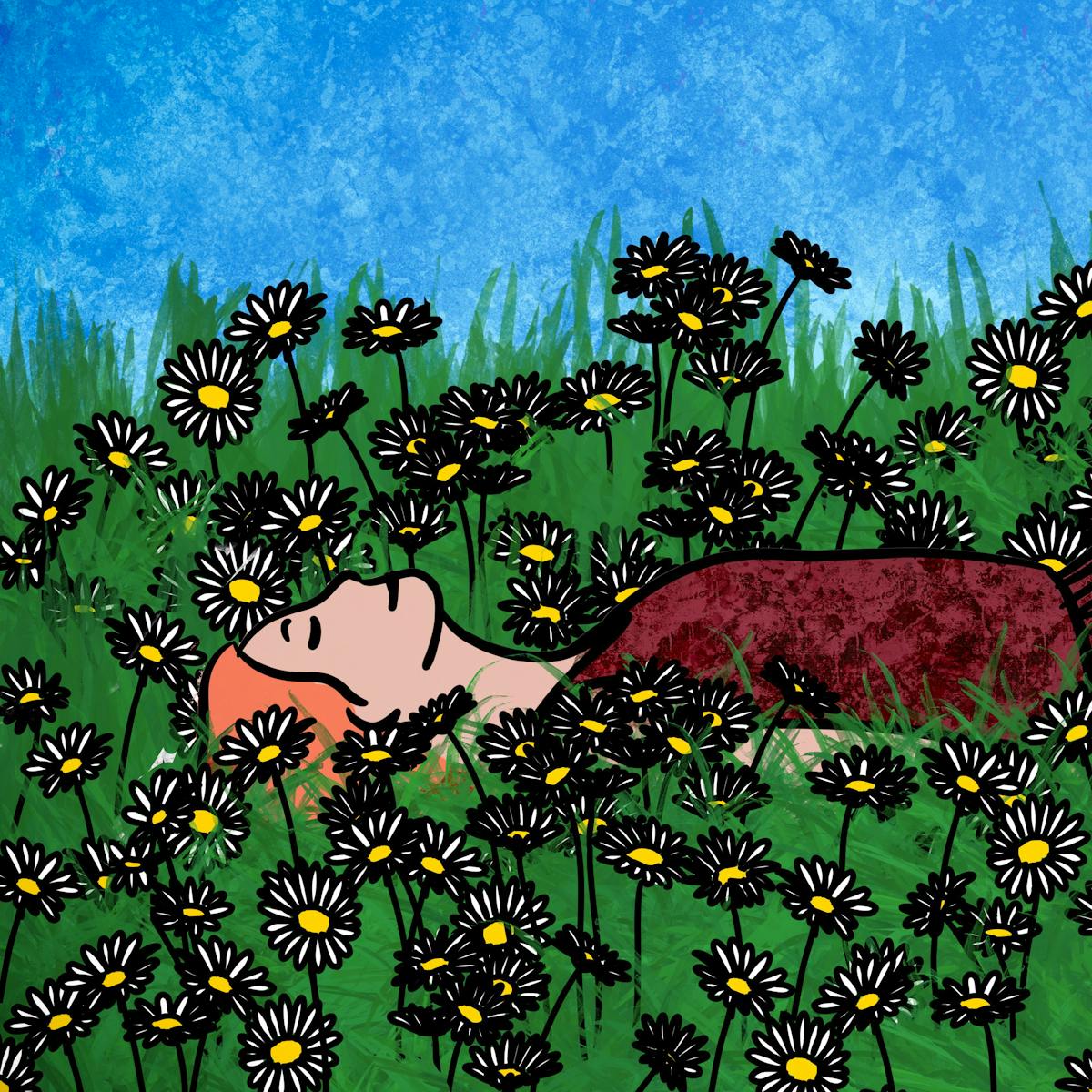

In 'Pollyana' by Eleanor H. Porter (published in 1913) the heroine finds resilience through looking for joy in the world.

Many who come to this story see this as a form of cheery denial. “Yes, you are hurting but, oh look, the flowers are pretty.” So ‘Pollyanna’ has made it into the dictionary as a term for someone who is overly optimistic, and even inappropriately cheerful in the face of life’s troubles.

This, though, is a misreading of the story and would definitely be a misreading of the spiritual truths behind it. Her Glad Game is a serious way of managing distress, not through denial but through a focus on the benevolence of God, who never leaves us comfortless.

It’s a choice to rejoice

We often assume that being glad is only a spontaneous emotional reaction: some events, people, sights, news, just fill us with joy. Psychologists recognise joy as one of the primary universal emotions. Yet rejoicing can also be a deliberate choice.

In the Psalms, the song book of the people of Israel and later the Church, we find the recitation of genuine troubles, hardship, fear and persecution, even the sense that God is absent. These laments are then followed by rejoicing in the God who will not abandon them, who in some way will make things right. The perspective shifts from the here and now to the long term; the troubles are very present now, but in the schemes of eternity, goodness and righteousness will flourish.

This deliberate turning to rejoicing is not a shying away from the reality of sadness, pain and distress. Instead it is about drawing on a deep sense of joy at being known and loved by God. It links to thankfulness and hope. The medieval mystic Julian of Norwich wrote out of her own experience of suffering about the love and joy to be found in her faith. In God, she tells us in ‘Revelations of Divine Love’, “All shall be well and all shall be well and all manner of things shall be well.”

Julian of Norwich (1342–c.1416) wrote about finding love and joy through her faith.

The psychologist and theologian Joanna Collicutt points out that joy is a profoundly social emotion that comes out of secure attachment. Joy is reinforced each time we reconnect with those who love us and who delight in us.

The universal games of peekaboo played with children build both a “tolerance of separation anxiety in the child” and a “store of joyful reunion experiences”, she says in her book ‘The Psychology of Christian Character Formation’. Joy comes out of the reinforcement that the one who loves us is there and delights in us.

Strength in the capacity for joy

So in terms of spiritual joy, we find that it is a byproduct of trust in the ‘parental’ love of God. One who will make things right, in the end, and one whose love for us is continually re-encountered each time we experience the connection through worship, prayer, the beauty of nature, the goodness we see as God-given. The Westminster Catechism, dating back to 1647, defines the “chief aim of man as to glorify God and enjoy him forever”.

There is joy to be found within the ups and downs of life because God is good and God’s perspective on life is eternal. As a child I learned many simple spiritual songs, such as “Joy, joy, joy / With joy my heart is ringing”.

Throughout my life, with times of blessing and times of adversity, the capacity to find joy in my faith has been a strength to enable me to cope well and to help others weather the storms.

Pollyanna does not underestimate the traumas of the world. She is an orphan who has known loss, poverty, displacement and disappointment. She has learned to trust in God and look for a perspective in life that helps her to live hopefully amidst all that she cannot control rather than falling into despair and bitterness at the unfairness of life.

The Glad Game does not diminish the reality of suffering; instead, it is a strength that opens up the possibility of joy.

About the contributors

Dr Emma Percy

Emma Percy is Chaplain of Trinity College Oxford. She was one of the first women ordained in the Church of England and continues to work for women’s full inclusion in the Church. She is a feminist practical theologian and is currently looking at the virtue of fortitude as a kind of spiritual resilience.

Jem Clancy

Jem is a visual and movement artist based in Leeds. She is passionate about dance and art as a means to communicate and connect with others. As a disabled artist she is particularly keen to embrace and promote diversity and inclusion throughout her work, in all processes and product. She is currently an associate artist with the Tetley Art Gallery and works at Northern Ballet supporting the Academy and the delivery of Ability, a weekly training course for adults with learning disabilities, in the Learning team.