In ‘Am I Normal?’, Sarah Chaney dives into the surprising history of how the notion of the normal came about, how it has shaped us all, and how it has been used as a tool of oppression. In this abridged extract, she explores how we came to believe that normality is an invisible law of nature, and introduces the science of comparisons that defined what ‘normal’ is.

The 200-year search for normal people

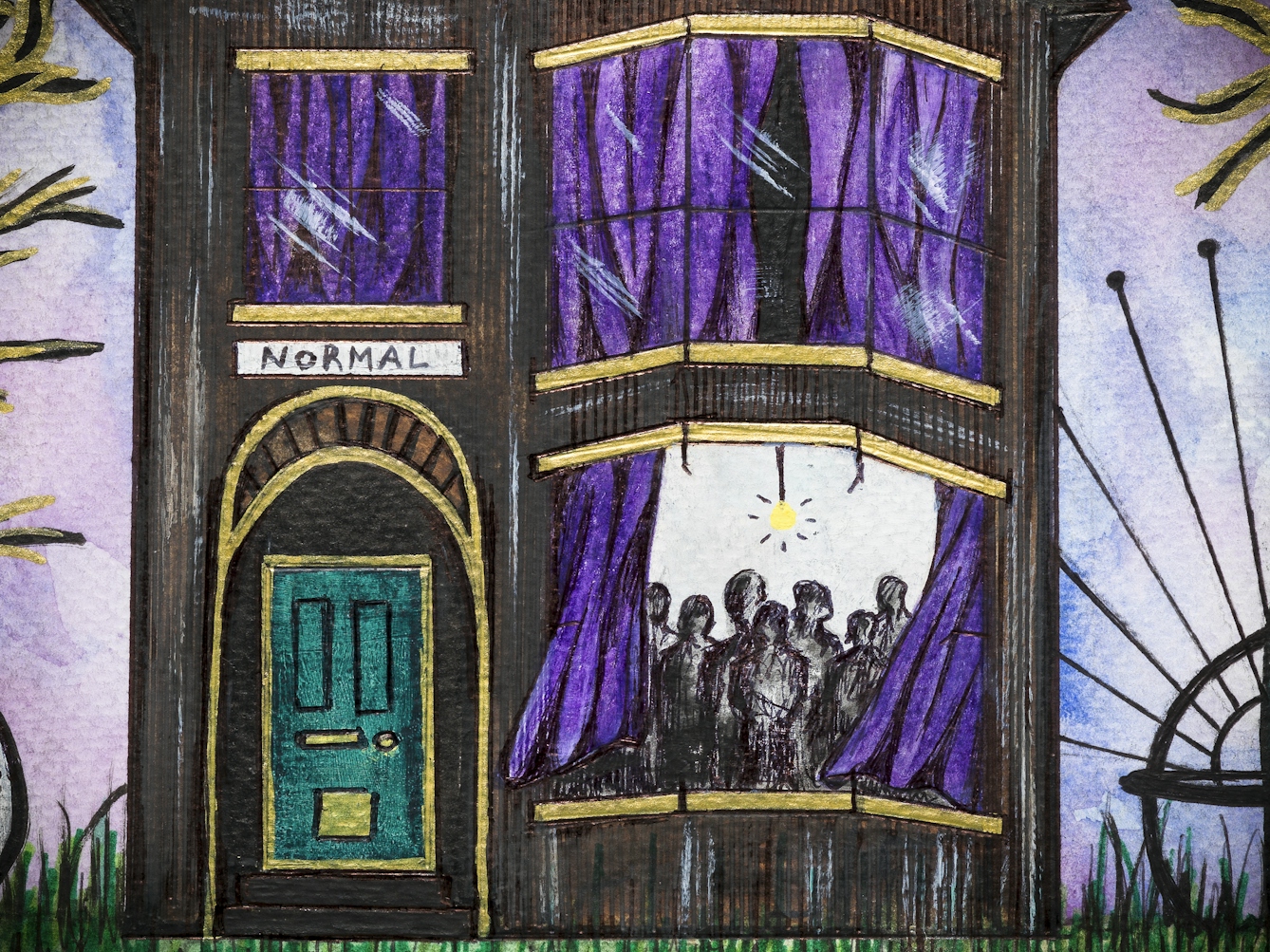

Words by Sarah Chaneyartwork by Maïa Walcottaverage reading time 9 minutes

- Book extract

Am I normal? It seems like a straightforward enough question, on the face of it. It’s something you might ask yourself on a regular basis. Is my body a normal shape or size? Is it normal to cry in front of others? To let my dog lick my face? To have heavy periods? To have sex with strangers? To feel anxious on public transport? To feel bloated after eating?

These and countless other questions frame and explain our lives. They help us negotiate our relationships with other people and work out when we might need intervention: the advice of a friend or a visit to the doctor.

They also prove how complex the idea of normality is.

What do we mean when we ask if we’re normal? Even just taking the questions in the paragraph above, this varies enormously. Sometimes we’re considering if we’re more or less average – or perhaps slightly above or below average, if that seems more socially desirable. I might want to be a little above average height, for example, and a little below average weight.

On other occasions, we’re wondering if we’re healthy. Is my blood pressure normal? If I feel pain in a certain place, is it a sign that something is medically wrong? If your child sleepwalks, this might be classed as normal, not because it’s common (a 2004 Sleep in America Poll found that just two per cent of school-aged children sleepwalk several nights a week or more), but because it’s not considered unhealthy.

Most often, however, when we ask if we’re normal we’re wondering if we’re like other people. Am I a typical example of the human race? Do I react in the same way as other people to situations? Do I look or dress or talk like other people? If I was more like them, would my life be easier?

These questions can have profound effects on our lives. I was a shy and awkward child, with thick, plastic-rimmed NHS glasses and much-loved home-knitted jumpers, who spent most of her time buried in books dreaming of a better, more magical world.

By the start of secondary school in the early 1990s, I was already marked out as abnormal, for reasons best known to my peers. ‘Creepy Phoebe’, they used to call me, after the bespectacled teenage ‘Neighbours’ character, whose father was a funeral director and scared her classmates by keeping pet snakes.

“I was a shy and awkward child, with thick, plastic-rimmed NHS glasses, who spent most of her time buried in books dreaming of a better, more magical world.”

By the age of 16 I was a ball of barely contained fury at the world, spending most of the school day wearing headphones so that no one would talk to me while I scratched Manic Street Preachers lyrics across every wooden school desk.

Does any of this sound familiar? If so, perhaps I was a normal teenager after all. But, like most teens, I never felt normal. As many bullied young people do, I accepted the outcast label that was handed to me and took it as my own (or so I thought), stubbornly exaggerating those differences my bullies commented on to distance myself from them still further.

It was stupid, I thought, for there to be a rule that wearing a backpack on both shoulders or pulling your socks up to keep your legs warm was ‘square’, so I insisted on doing both. I didn’t want to wear make-up and listen to pop music but to spend every glorious Wednesday with my head buried in the new issue of NME or Melody Maker, reading about bands no one else in my school had even heard of.

Despite all this, there was a part of me that longed to be normal. If one of the bands I liked made the Top 10, I felt like I’d achieved something – other people liked something I did!

The normal was a mysteriously vague ideal that stayed with me throughout early adulthood, brought into sharp relief by a dread of not fitting in, a fear of being abandoned and alone, and a sense that if something magically changed in or about me, then everything would suddenly be okay. I was probably approaching thirty before I ever really questioned what I meant by “being normal”.

The short history of worrying about being normal

In some circumstances people have always judged themselves by those around them or criticised others for not fitting in. However, it was only in the last 200 years that this began to happen on a widespread scale, enshrined in scientific practice in Europe and North America through medicine, physiology, psychology, sociology and criminology – driven by the rapid rise of statistics.

Normality became bound up in our laws, our social structures and our ideas of health. But before 1800, the word ‘normal’ was not even associated with human behaviour at all. Normal was a mathematical term, referring to a right angle.

“Colonial expansion by Western countries sent scientists out to measure and define around the globe, comparing the population of their own homelands with people elsewhere – almost always in ways that favoured white people.”

The growing popularity of statistics in Europe and North America in the 19th century inspired scientists to measure humanity to find first an average, and then a norm. These norms could not have been set without the standardisation of huge swathes of human life that defined what and who was normal – and by implication most human, most valuable.

The introduction of compulsory education in many countries, for example, led to the identification of children who learned more slowly than their classmates, while the creation of national insurance and occupational compensation schemes demanded medical screening with increasingly detailed definitions of normal health.

Baby-weighing clinics gave rise to enduring ideas about childhood development, IQ tests began to establish norms of intelligence, and factories and industrial workplaces gave rise to notions of the ideal worker and standard productivity levels.

Colonial expansion by Western countries sent scientists out to measure and define around the globe, comparing the population of their own homelands with people elsewhere – almost always in ways that favoured white people. This book focuses on Europe and North America simply because that was where the so-called normal was born: the assumption that these standards applied to the rest of the world was just that, an assumption.

The science of the normal is also a story about the othering of whole communities.

The science of the normal these researchers created is also, then, a story about the othering of whole communities, defined in opposition to Western standards of the ‘right’ way for a person to be. The scientists, doctors and scholars who attempted to measure and standardise humanity were overwhelmingly white, wealthy, Western men, who were exclusively heterosexual (at least in public).

They tended to support the status quo – which they had to thank for their success – and marginalise other groups in the process. When they desired change, it was most often change that benefited their educated, professional class. This is not to say that this was always intentional or that none of these men ever supported those less privileged. Some called themselves socialists; others backed the feminist movement, denounced imperial aggression, or argued that homosexuality should be legalised.

Yet most of these men also assumed that their place at the top of the social ladder was simply the natural order of things. They had been born into the highest stage of human evolution – or so they believed – and charitably sought to set a standard to help others improve.

“The scientists, doctors and scholars who attempted to measure and standardise humanity were overwhelmingly white, wealthy, Western men, who were exclusively heterosexual (at least in public).”

One of the arguments they made to justify colonialism was that the lives of the peoples colonised were improved by being guided in Western norms – or rather, as we might put it today, by having Western norms brutally enforced upon them.

But is it merely a sobering thought to recall how many people have been killed, imprisoned, ruled insane or otherwise excluded from society because of the shifting notion of what’s normal? Or is there something more we can take from this history? I believe there is.

How a minority came to define the notion of ‘normal’

Although we constantly refine and expand our definitions of what is normal, natural or desirable, many of us never stop to consider if there is such a thing at all. We just assume the normal exists, an invisible law of nature – perhaps slightly to the left or right of where our parents or our grandparents told us it was, but there nonetheless.

Yet this so-called normal may not even be all that usual. In 2010, three North American behavioural scientists suggested that the subsection of the world’s population from which today’s scientific norms are drawn – which differs surprisingly little from the groups studied by 19th-century scientists – might be the ‘WEIRDest people in the world’.

People from WEIRD (that is Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic) societies make up just 12 per cent of the world’s population but 96 per cent of subjects in psychology studies and 80 per cent in medicine. They are assumed to be white – even when they are not – because white is supposed to be a neutral category as far as science and medicine is concerned. The Victorian science of the ‘normal’ has a long legacy.

So how has our history led us to a position where such a tiny group continues to dominate narratives of what it is to be ‘normal’?

By exploring the history of the contested ways in which norms and standards have been adopted, I hope to encourage you to question not only what you think of as normal, but also why we are so ready to define ourselves by such prescriptive judgements. I invite you to consider how the ‘normal’ permeates our lives and the impact it has on us, whether you are WEIRD or not.

It may be normal to worry about being normal. But that shouldn’t stop us questioning the very idea.

‘Am I Normal?’ is out now.

About the contributors

Sarah Chaney

Sarah Chaney is a research fellow at the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions. She spent her teens and 20s furiously rebelling against the mainstream, while secretly longing to be normal. It wasn’t until she passed 30 that she (mostly) stopped worrying about this mythical ideal. Alongside her research work she runs the public exhibitions and events programme at the Royal College of Nursing, occasionally writes for The Conversation and Psychology Today, and reads far too much X-Men fanfic.

Maïa Walcott

Maïa is a Social Anthropology undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh and a multidisciplinary artist working with sculpture, painting, illustration and photography. Her work has been widely published and exhibited, appearing in the anthology ‘The Colour of Madness’ and as part of ‘Project Myopia’. Maïa was also the in-house illustrator for the literary magazine The Selkie, and photographer for photo exhibitions such as ‘The I'm Tired Project’ and ‘Celestial Bodies’.