Adults are often dismissive about the moods and intense feelings adolescents experience, but as the brain and body go through significant change, highs and lows are inevitable. At an inner-city youth club, Kate Wilkinson talks to teens about stereotypes and emotions.

This is a MOOD

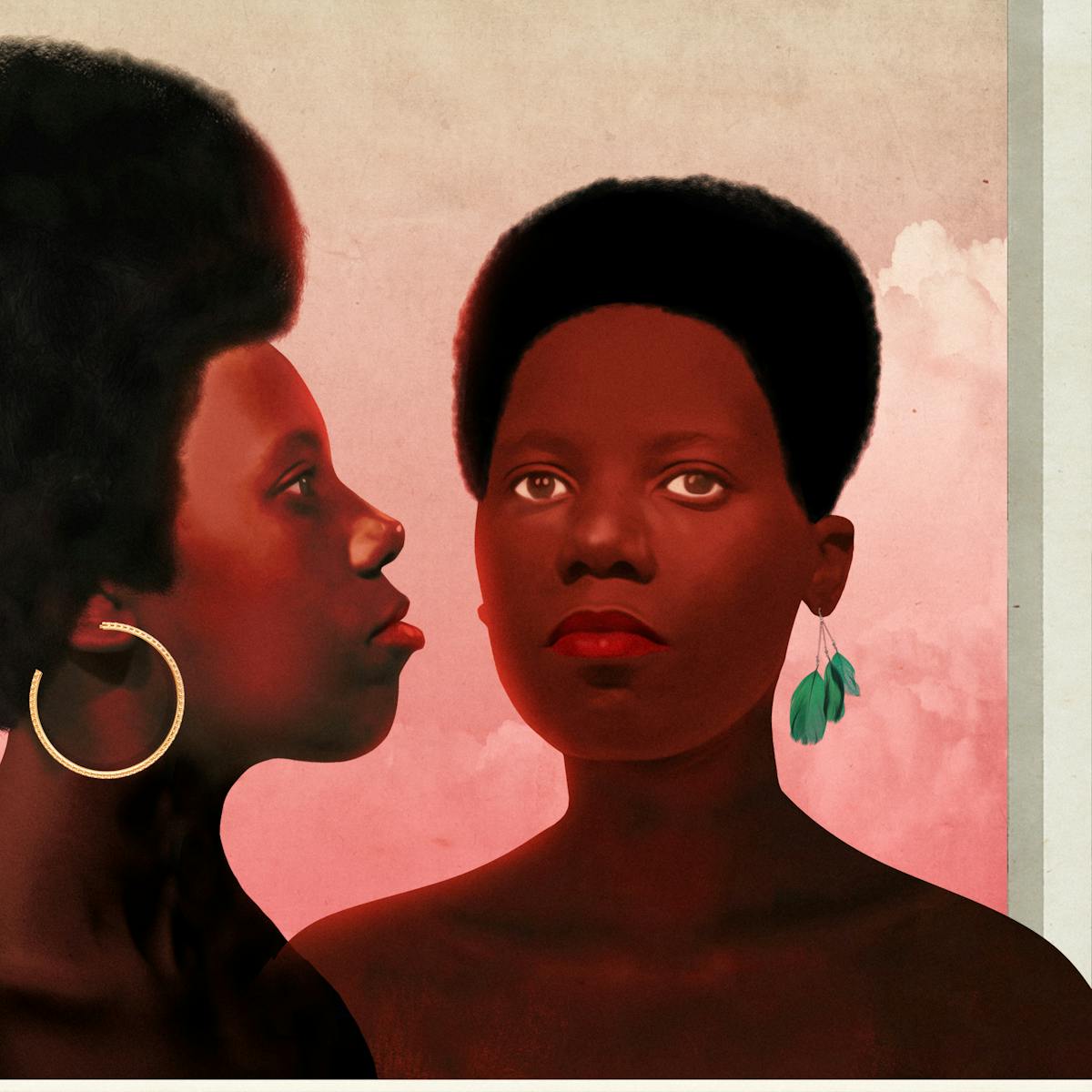

Words by Kate Wilkinsonartwork by Laurindo Felicianoaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

A body is your own emotional fairground ride: you’ve bought the ticket but you’re not in control. Sometimes the highest and lowest emotional points in our lives are not the result of horrific and bravely fought trials, but instead the seemingly random impulses of “brain chemistry”, hormonal shifts, changes in the water, whatever you want to call it.

Over the years I’ve become familiar with the pattern of my mood just before my period starts. I feel more easily aroused, more prone to tears, more sentimental. I quite like it. When the blood starts, I almost always feel a small swell of relief that I’m not pregnant, before I get uncomfortable, greasy-skinned and achy.

But even then, I’m lucky my periods aren’t particularly bad compared with many other women. I missed them during the six months I took the contraceptive pill and everything flattened out.

However familiar the experience is now, my first period felt new and unsettling. Adolescence is defined in many ways, but most definitions say it begins at the onset of puberty, when children start to develop the sexual characteristics of adults. Hormones surge, as powerful as the sea. The NHS page about puberty lists typical changes over time that recall the sort of dramatic bodily transformation you might see in a superhero movie.

Like me, 14-year-old Kiara experiences a change in mood during her period. “Sometimes when you’re on your period, you’re just like: get out my face. You just shut people out,” she says. Also like me, she finds positive aspects to her body’s unbidden changes.

“I remember my stepsister used to have bigger shape and body to me, and it used to make me kind of jealous. I thought, ‘You look really nice in the stuff you wear,’ and I was like, everything just looks odd on me. Eventually I grew, and it just doesn’t bother me as much any more. I don’t have to act ‘moody’ around her.”

“Hormones surge, as powerful as the sea. The NHS page about puberty lists typical changes over time that recall the sort of dramatic bodily transformation you might see in a superhero movie.”

Pubertal hormones do affect mood, but they aren’t everything. Psychologists and neuroscientists who work with young people acknowledge more complex shifts and wider patterns in neurological development. Cat Sebastian joined the Wellcome Trust as Evidence Lead for the Mental Health Priority Area after an academic career in cognitive and affective neuroscience.

Even in the time that she’s been working, our understanding of teenagers has shifted: “When I was growing up, it was all talked about in terms of hormones… Now people are much more aware of the broader changes that are happening and the brain development that’s ongoing, although now it just seems to have changed from, ‘Oh, their hormones are playing up,’ to, ‘Their brain is still developing.’”

Either way, adults are often dismissive of teenagers and their feelings. Nevertheless, teenagers report both higher highs and lower lows than older age groups.

A time of change

The Lambeth youth group that Kiara attends with her 17-year-old cousin Yassmin is usually open three evenings a week. The week after I visited the youth centre, the government announced a nationwide lockdown to combat the coronavirus pandemic. For over a year, young people lost access to these important social spaces.

At first Kiara seems reluctant to speak to me, but as she grips her cousin’s arm and peers at me, there’s a glint in her eye that makes it seem like this whole interaction is a game to her.

Later Yassmin tells me Kiara is her “funniest cousin”. The topic of the moody teenager interests Yassmin and she readily owns up to having “attitude”. But Kiara recognises that her school identity isn’t the full picture: “Outside of school I know I have people who love me. I go to church regularly; my mum and dad are not together, but he still tries to look after me and my mum does her utmost to do everything for me – so I’m happy.”

Even as our knowledge of the brain improves, the stereotype of the moody teenager persists in the popular imagination. The American psychologist G Stanley Hall popularised the idea of adolescence as a time of “storm and stress” through the publication of ‘Adolescence’ in 1904.

“Outside of school I know I have people who love me. My mum and dad are not together, but he still tries to look after me and my mum does her utmost to do everything for me – so I’m happy.”

In many cultures, the teenage years are a time of change in circumstance as well as biology. Moving from secondary school to college or university, from living with parents to living apart, dependent child to working adult. These transitions can certainly be stressful. Perhaps the idea of “storm and stress” bears a grain of truth?

Filipe is 17 and speaks in a low, quiet voice, neither face nor body moving much during our chat. But he’s open and honest. Like most of the young people I speak to, he had trouble in school with his behaviour. “Obviously, I was a kid,” he explains.

Even as our knowledge of the brain improves, the stereotype of the moody teenager persists in the popular imagination.

A couple of years have made a difference to Filipe’s sense of himself. He says, “I think my personality has changed, ’cos back then I used to be childish. Now I’ve matured up, ’cos life’s hit me. You always get them stages.”

Rather than being a source of stress, the transition to college has been a positive one. I ask him why things were so much more difficult in school, and he puts it down to the people he used to hang out with. College is better, he says, because “people treat you equally”. At school, “people would say something” if he wore old, broken-down trainers. “But now I can just walk in my slippers or something, my sliders, and no one will say nothing,” he says.

The developing brain

Yassmin is a student paramedic. Like Filipe, she seems caught between child and adult worlds. She tells me about the time she was called out to the scene of a car crash, and there was a woman on the side of the road giving birth.

In the middle of telling the story Yassmin suddenly turns and yells, “Go away, you fat shit!” to one of the boys making noise by the table football behind us. “We went to nursery together, that’s why we’re like this,” she explains to me, and continues to tell her story. One moment she’s a proud student paramedic who’s witnessed a traumatic childbirth, the next she’s bickering and laughing like a child.

“Moody, hormonal, overemotional – these pejorative terms are levelled at women as well as teenagers. Emotion is something to be controlled, not embraced. But it was emotion that I missed when I took the contraceptive pill.”

Perhaps it’s that ambiguity that adults can struggle with. On the one hand, telling teenagers to “grow up”. On the other, restricting their freedom and talking down to them. But they aren’t children or adults; they are adolescents.

Because the experience of young people varies hugely across time and cultures, some believe that adolescence is a wholly invented idea. Why not just have ‘child’ and ‘adult’?

In ‘Inventing Ourselves’, neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore argues that adolescence is a developmentally important stage, with key moments observable across cultures and eras. Resilience to change is developing, emotion regulation and cognitive control in key areas are being learned.

But, she says, “[the teenage brain] isn’t broken. It’s not a defective adult brain. We shouldn’t demonise it.”

Moody, hormonal, overemotional – these pejorative terms are levelled at women as well as teenagers. Younger generations are criticised for being oversensitive ‘snowflakes’. Emotion is something to be controlled, not embraced. But it was emotion that I missed when I took the contraceptive pill.

I’ve had times when emotion has controlled me, low mood making it debilitatingly hard to do anything. But in the context of adolescence, it’s ‘normal’ to go through more intense feelings. I look back to my teenage years with a curious mix of both regret and relief that I don’t feel things quite as passionately as I did then.

The young people I spoke to seemed to think that being an adult was harder. Filipe said, “It’s not a difficult time because you don’t have to pay your rent. You’re still free – to do certain things.”

About the contributors

Kate Wilkinson

Kate works at Pushkin Press. When not submerged in a book, she can be found walking or practising Spanish. Sometimes both at once.

Laurindo Feliciano

Laurindo Feliciano is a Brazilian contemporary artist and illustrator who has been living and working in France since 2003. Inspired by vintage aesthetics, he creates illustrations using techniques such as collage and digital painting. All his illustrations and posters share a certain nostalgic flair and a great passion for surrealism. His work has been published and exhibited in several countries, and in 2014 he won the AOI (Association of Illustrators) Professional Editorial Award. Among his clients and collaborations are the Musée des Arts Décoratifs/Paris, the V&A, British Airways, WIRED, the Financial Times, Penguin Vintage, Netflix, and many others.