When Frodo in ‘The Lord of the Rings’ seems to reject simple happiness and all he’d fought to achieve, the child that was Kate Wilkinson was puzzled. Fast-forward a couple of decades, and her adult self appreciates the power of redemption in fantasy fiction, as well as the complexities of characters like Frodo.

What happy endings teach us in childhood

Words by Kate Wilkinsonartwork by Laurindo Felicianoaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

As I walked through the children’s section of my local library in Lambeth, I was reminded of the many trilogies, chronicles and sagas I read as a child. The books’ worn spines still glinted with the promise of fantasy.

A common narrative that unites many of these books involves a hero, a calling to overcome an evil force, multiple challenges and hardships in which lessons are learned and, finally, a satisfying ending in which good triumphs over evil and all is resolved.

This theory was confirmed when I stumbled across Fantasy Plot Generator and created my own little story called ‘Wate Kilkinson, The Gremlin’, most of the details of which are auto-generated. At the end, Wate “returns home to his bungalow a very wealthy gremlin”. Wate’s fate might seem laughably simplistic, but many fantasy tales do include deep psychological insight and moments of wonder that are equal to those found in any other art form, literary or otherwise.

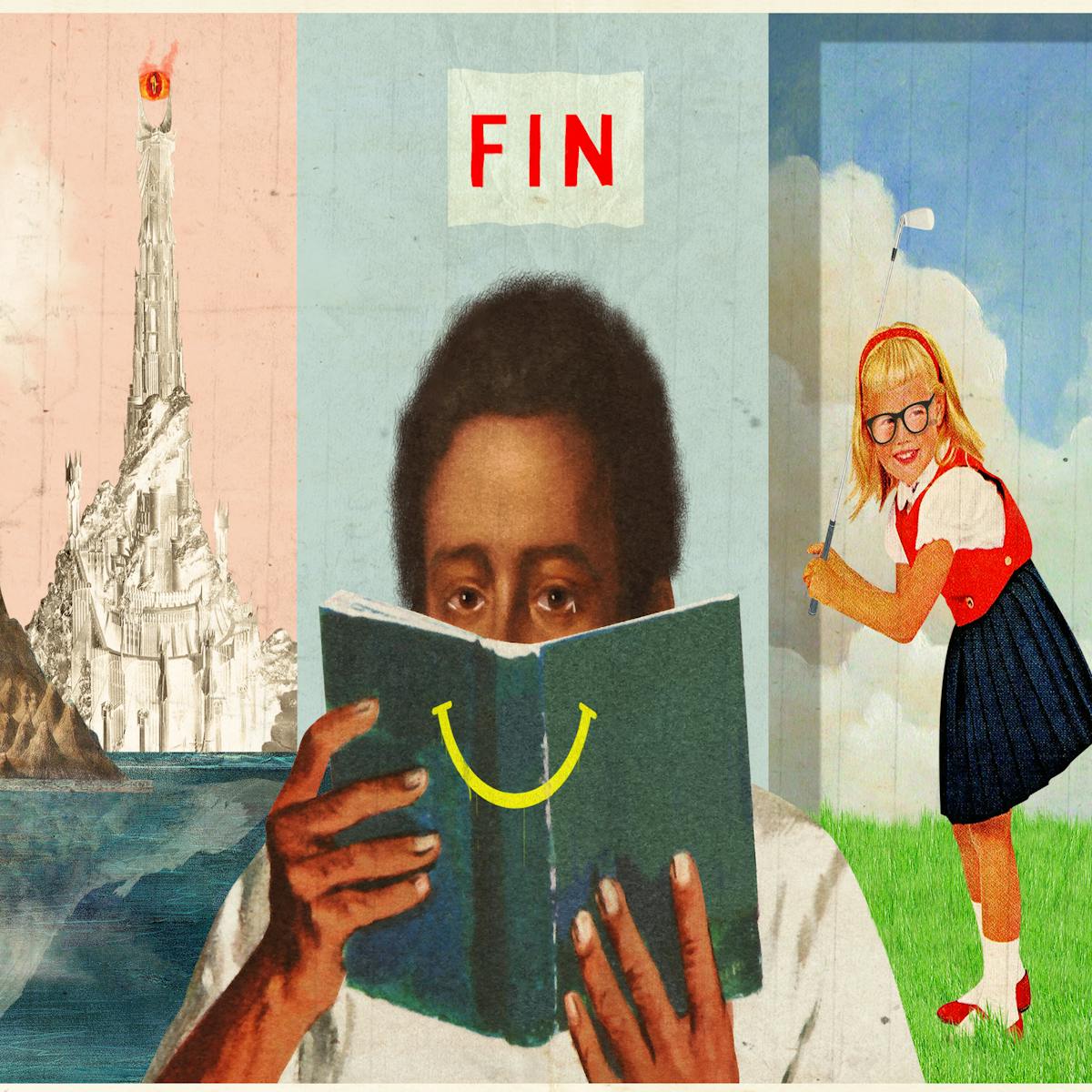

One of my favourite fantasies was and still is ‘The Lord of the Rings’, though it was Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of J R R Tolkien’s classic trilogy that became lodged in my young imagination, rather than the books. ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’ (2001) was released when I was seven and it was the first film I saw in the cinema after ‘Rugrats in Paris: The Movie’ (2000). I knew it would be scary for me, but I was desperate to keep up with my brothers, who were both keen to see it.

By the end of the three-hour final film one of my strongest impressions was that Sam – Frodo’s gardener sidekick – was the story’s true hero, literally carrying Frodo to the finish line. On returning to his home in the Shire, Sam marries his she-hobbit sweetheart and the film’s closing sequence features their beautiful chubby family smiling outside their hobbit-hole.

“By the end of the final film one of my strongest impressions was that Sam – Frodo’s gardener sidekick – was the story’s true hero, literally carrying Frodo to the finish line.”

Frodo, the ostensible hero, is a different matter. After three films spent moaning and jeopardising his own quest, he finally sees the ring destroyed and evil Sauron defeated. Yet at the end, he’s still sad-eyed. He’s not content to stay in the Shire with the rest of his friends but departs on a ship with some elves to the mysterious ‘Grey Havens’.

As a child I had little sympathy for Frodo and his confusing behaviour. “I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me,” he says. Not for you! Who do you think you are, Frodo?

Secular narratives of salvation

Endings are a tricky matter for storytellers. Peter Jackson was criticised for giving his film too many and for taking too long, though that challenge had already been set by Tolkien’s many narrative strands, some of which didn’t find space in the films. However complex and many-stranded the ending, and however the principal characters feel, the overriding conclusion needs to be happy, in the sense that good must triumph over evil.

I asked my friend, an editor of children’s books, whether she knew of her publisher ever putting out a fantasy book with an ambiguous or unhappy ending. She couldn’t think of any.

However complex and many-stranded the ending, the overriding conclusion needs to be happy, in the sense that good must triumph over evil.

As a Christian, Tolkien conceived the happy ending as more than just a fictional trope; it corresponded with his theology. God has provided the ultimate happy ending by redeeming mankind through the death and resurrection of Jesus. This is the definitive example of what Tolkein called a “eucatastrophe” – a sudden turn of events at the end of a story which ensures that the main character doesn't meet a terrible and likely doom.

“I asked my friend, an editor of children’s books, whether she knew of her publisher ever putting out a fantasy book with an ambiguous or unhappy ending. She couldn’t think of any.”

In Tolkien’s fiction, an example is the eagles who swoop to our heroes’ rescue more than once. We might scoff at their convenience, but they’re an integral part of Tolkien’s world rather than a lazy plot device.

It's not only Tolkien’s world, of course. Christian culture still exerts enormous influence on secular societies, and many religious narratives across the world tend towards redemption and salvation.

In ‘On Fairy-Stories’, Tolkien writes that the happy ending gives us “a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief”. Against overwhelming odds, hoping that everything will turn out OK feels spiritual, looking for some kind of cosmic favour “beyond the walls of the world”. But the happy ending remains powerful, even in secular narratives.

The fantasy genre is sometimes criticised for being escapist. All these stories with happy endings – perhaps they’re giving children an unrealistic idea of how life will turn out for them. Back in the library, I’m trying to focus on writing, but some children aren’t respecting the “quiet area” signs. So I ask one of them about this issue. He mumbles, “I don’t think happy endings happen very much in real life, I think life is a bit more complicated than stories.”

We underestimate children if we think they’re unable to distinguish between stories and life. Their ideas about the world are constantly being informed by their environment and experiences, including, but not restricted to, films and books.

When I was a child, I might have briefly entertained ideas of destroying evil by becoming some kind of saintly do-gooder, though that would have come from my Catholic upbringing as much as ‘The Lord of the Rings’.

“We underestimate children if we think they’re unable to distinguish between stories and life. Their ideas about the world are constantly being informed by their environment and experiences.”

Achieving our dreams

At some point I became less interested in the heroic quest and lost my idealistic confidence in moral certainties. Dreams of heroism gave way to something more bourgeois. I could do anything I wanted, I was told, and it didn’t occur to me to want anything other than the conventional middle-class trajectory of passing exams, achieving a place at university, and getting a job that would reflect my specialness.

This drive for achievement sat alongside the feeling that it was important to find my true love, before the complexity of sex and relationships started to erode this simple romanticism too.

What if you followed the path set out for you and overcame all the obstacles, achieving the goals you’d pursued? Would you be happy then? Tolkien honours the happy ending with his heroes successfully completing their quest. But through Frodo’s complicated behaviour, he smuggles into a heroic story the unsettling idea that achieving our goals might not leave us feeling happy.

As a child I couldn’t recognise the symptoms of trauma, but it’s clear that Frodo is traumatised by his quest. His challenges may have taught him something, but they’ve also been a burden, leaving him unable to enjoy things in the same way as before.

“How do you pick up the threads of an old life?” Frodo says, “How do you go on when in your heart you begin to understand there is no going back? There are some things that time cannot mend, some hurts that go too deep, that have taken hold.”

It’s only by growing older and living my own life that I’ve been able to understand his response. By the time we are anywhere near achieving our childhood dreams, we will have become different people. And that’s a good thing.

About the contributors

Kate Wilkinson

Kate works at Pushkin Press. When not submerged in a book, she can be found walking or practising Spanish. Sometimes both at once.

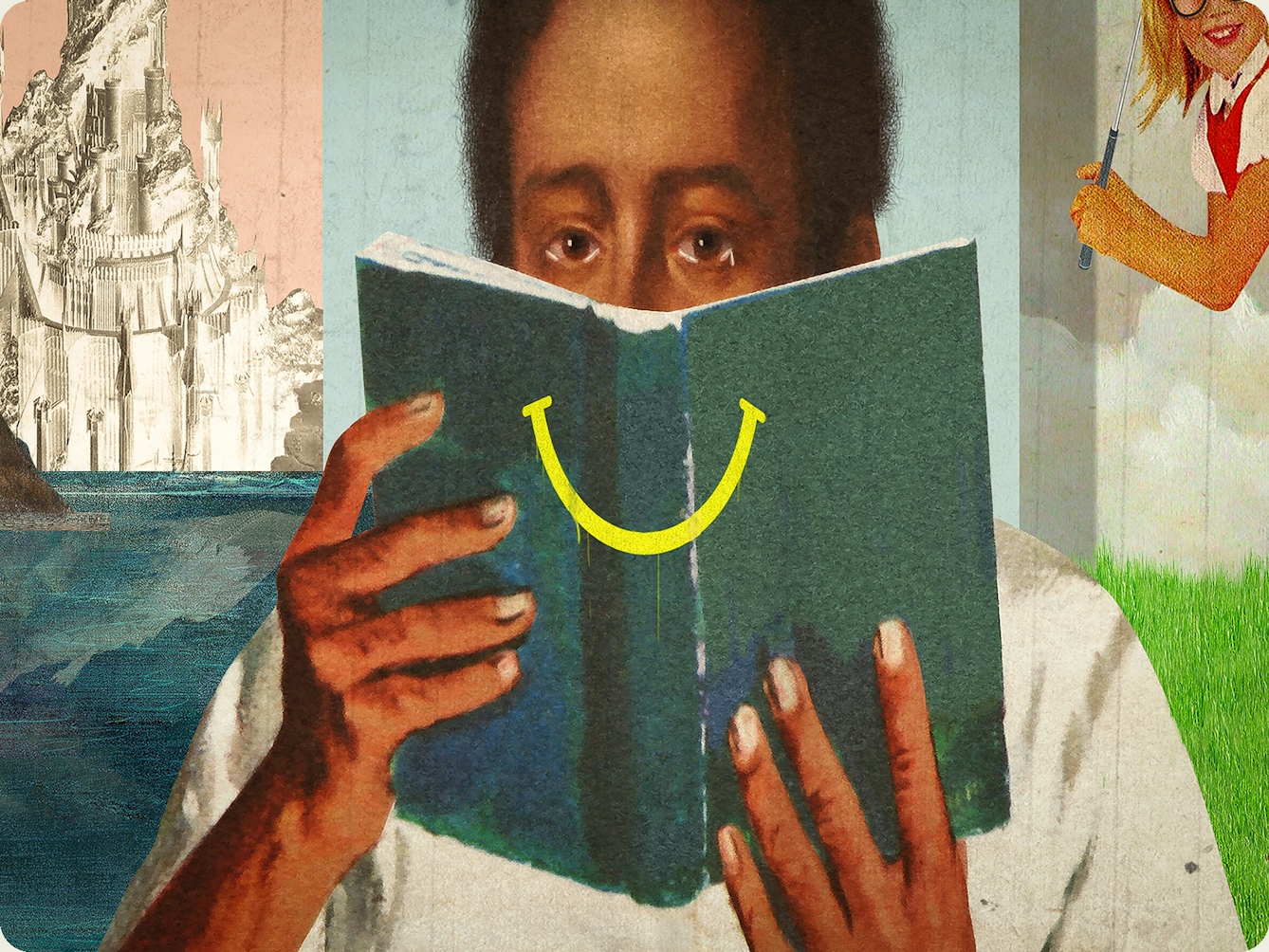

Laurindo Feliciano

Laurindo Feliciano is a Brazilian contemporary artist and illustrator who has been living and working in France since 2003. Inspired by vintage aesthetics, he creates illustrations using techniques such as collage and digital painting. All his illustrations and posters share a certain nostalgic flair and a great passion for surrealism. His work has been published and exhibited in several countries, and in 2014 he won the AOI (Association of Illustrators) Professional Editorial Award. Among his clients and collaborations are the Musée des Arts Décoratifs/Paris, the V&A, British Airways, WIRED, the Financial Times, Penguin Vintage, Netflix, and many others.