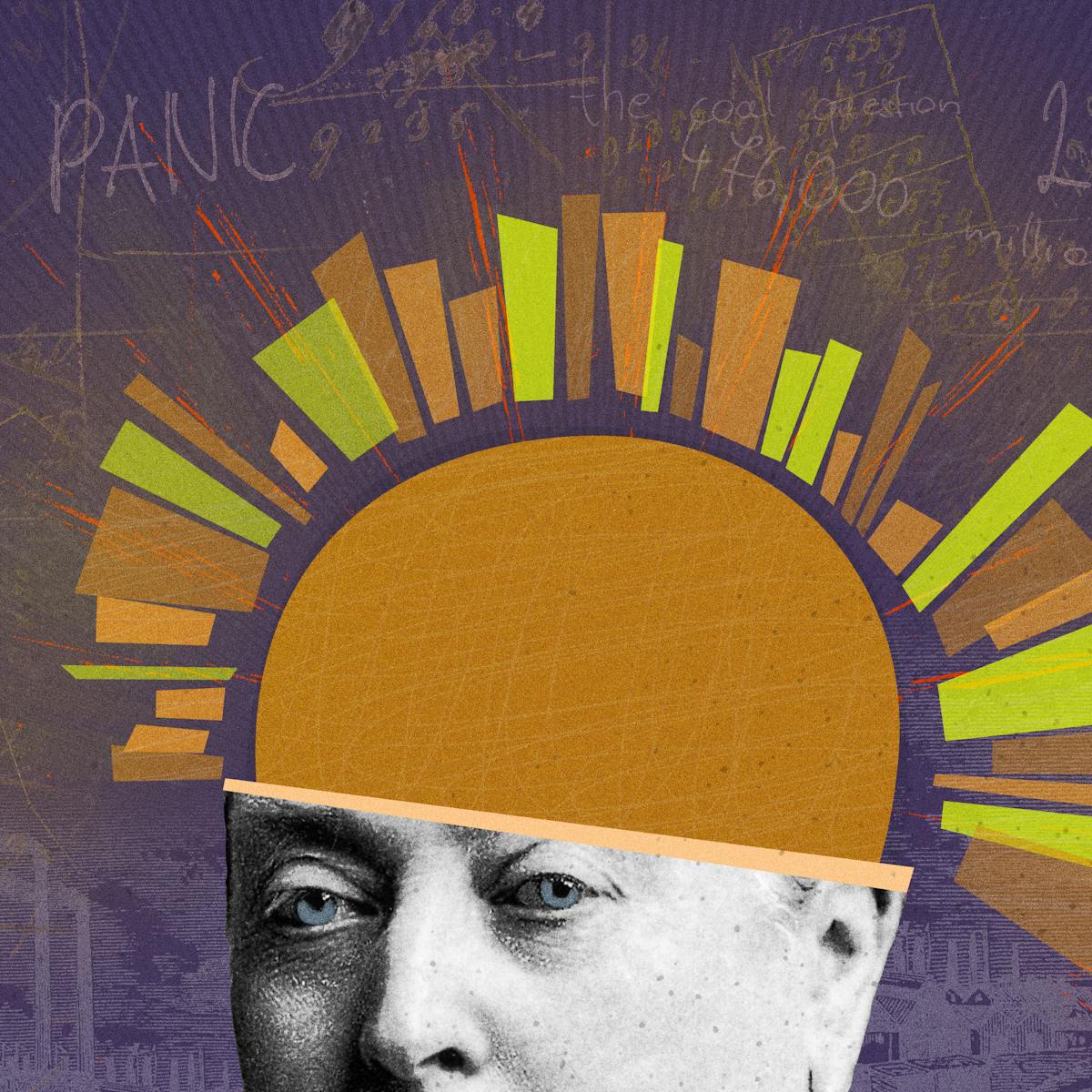

Victorian captains of industry were determined to keep a tenacious grip on Britain’s global industrial dominance. But fears of accessible coal stocks being exhausted, and even of the sun’s power burning out, caused the nation’s scientists to predict mass poverty or, perhaps, total extinction.

When the sun goes down

Words by Charlotte Sleighartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

It was a logical thought for the coal-fired Victorians, gathered around their winter hearths. Just as a fire glows red and burns out to grey ashes, so must the sun eventually run out of fuel and chill to nothing within the vast arc of the heavens. The question was: how long would it take?

Britain was a nation of engineers, and heat calculations were its strong suit. The sun could be compared to 476,000 million million million horsepower. And that – with furious scribbling of pencil on ledger – came out at just 21 more years at the present rate of burning.

At least, that was the lowest estimate. The celebrity physicist William Thomson, famed for laying a telegraph cable across the bed of the Atlantic Ocean, had a more reassuring answer. It wasn’t just a matter of consuming fuel; the slowly collapsing sun generated additional heat through its own increased gravity.

When will the sun die?

Thompson’s calculations pushed the end forward to around 10 million years hence – though this, soberingly, was only half the length of the sun’s existence to date. It was, in other words, two-thirds of the way through its life.

That suns could flare up and die was impressed upon the public imagination in 1866, when astronomer William Huggins discovered an exploding star in deep space. “For aught we know,” wrote one journalist, the same fate might affect our own solar system. In that case, “all life would be destroyed from this earth… in the course of less than a day”.

Generally, however, it was the fate of gradual solar cooling that preoccupied the Victorian mind. Darwin wrote in his autobiography of the “view now held by most physicists” that “the sun with all the planets will in time grow too cold for life”. It was, for Darwin, “an intolerable thought” that the evolutionary progress of humans would so casually and finally be wiped from the universe.

The fearful anticipation of death comes to most of us sooner or later, but what made the Victorians project it onto the myth of the death of the sun in particular?

“Just as a fire glows red and burns out to grey ashes, so must the sun eventually run out of fuel and chill to nothing within the vast arc of the heavens.”

Predicting tomorrow’s sunrise

The reliable rising of the sun held, and still holds, a special place in the mythology of the scientific method. In 1772, the Scottish philosopher David Hume used the anticipation of the sunrise as an example of a hypothesis that must be proved by induction (that is, by collecting observations and generalising from them). His point was that we can recognise an idea that is provable in this way because – however unlikely it may seem – we can imagine a counter-scenario: in this case, that the sun does not rise.

Hume’s throwaway example took on a life of its own, with the Frenchman Pierre-Simon Laplace attempting to calculate the actual inductive probability of the sun’s rising tomorrow. Although Laplace intended the calculation as a theoretical exercise in probability, his special fame in the world of astronomy seems to have confused some people into thinking his result (a reassuring odds-on 1,826,200 to 1) was a practical prediction, raising the small but real possibility of the sun’s not rising.

Laplace’s rising of the sun became embedded as a definitive example of inductive reasoning, taught to successive generations of philosophers and scientists. It was a story that characterised and vindicated the inductive method of science that was so important to the Victorians.

‘We’, the civilised and scientific, know that the sun will rise; this fact is sustained by the complementary myth that one of the chief characteristics of ‘savages’ is their persistent fear that it will not. Cowering fearfully in their dark caves, they sacrifice to vengeful gods in the hopes of bringing it back in the morning. Or so the story goes.

Although there are solar-related triumphs of prehistoric architecture (such as Stonehenge) there is little, if any, evidence of this jittery cave-dweller. It is, in fact, the invention of Victorian anthropologists, vindicating the triumph of inductive science and engineering through the myth of its prehistoric absence.

Yet fear nibbled away at this sustaining solar myth of Victorian supremacy through science. One reason for this concerned the British Empire – that global scattering of hijacked lands on which, as the saying went, the sun never set. Coal was the energetic ‘sunshine’ for an empire that ran on coal-fired factories, steamships and railways. But scientists began to fear that coal would run out.

“Coal was the energetic ‘sunshine’ for an empire that ran on coal-fired factories, steamships and railways. But scientitst began to fear that coal would run out.”

The prospect of industrial decline

In 1854, a young man faced up to the failure of the imperial industrial project. His name was William Stanley Jevons, and much to the dismay of his parents and siblings, his father’s businesses in invention and iron all collapsed. Perhaps it was the experience of family decline that led Jevons to contemplate the possibility of failure on a larger scale.

Just over a decade later, he published ‘The Coal Question’, arguing that, soon, hard-to-reach and more expensive coal would be needed to satisfy demand, bringing progress to a halt. Within decades, the country would be “thrown back into the laborious poverty of early times”, its prospects “shortened and darkened”. Jevons’ calculations were discussed in Parliament, and newspapers reported a “coal panic”.

Energy from coal and energy from the sun were, scientifically, all one and the same to the Victorians. Any form of energy can be converted to any other, as Thomson had shown. But politically, coal and sunshine were not at all equivalent.

Jevons contemplated the possibility of solar energy as an alternative to coal, concluding with a shudder that “such a discovery would simply destroy our peculiar industrial supremacy”. Britain had more coal than other nations and this was the secret of her success. Solar energy would be available to all. Electricity, he warned “has already been zealously cultivated on the Continent” with the aim of destroying England’s industrial dominance.

What Jevons and the Victorians truly feared wasn’t so much the loss of energy as the sharing of it. Their desperate grasp on British industrial superiority was a significant cause of the Great War, culminating in the loss of around 20 million lives.

What began as a plausible question about physics ended up entangled in an idolisation of science as both identity and the source of material supremacy. It is a warning of what might lie in store if the world's wealthy treat the gathering catastrophe as a threat to their personal preservation rather than an entreaty for global justice.

About the contributors

Charlotte Sleigh

Charlotte Sleigh is an interdisciplinary writer and practitioner in the science humanities. Her most recent book is ‘Human’ (Reaktion, 2020). She is Honorary Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and current president of the British Society for the History of Science.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.