Artist Audrey Amiss documented the last day of her life by pasting some food packaging into a scrapbook, and recording in words and images the things she noticed in her final hours. Elena Carter, an archivist at Wellcome Collection, describes her first encounter with these fragments, and the impact of the extraordinary collection Audrey left behind.

Who was Audrey Amiss?

Words by Elena Carteraverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

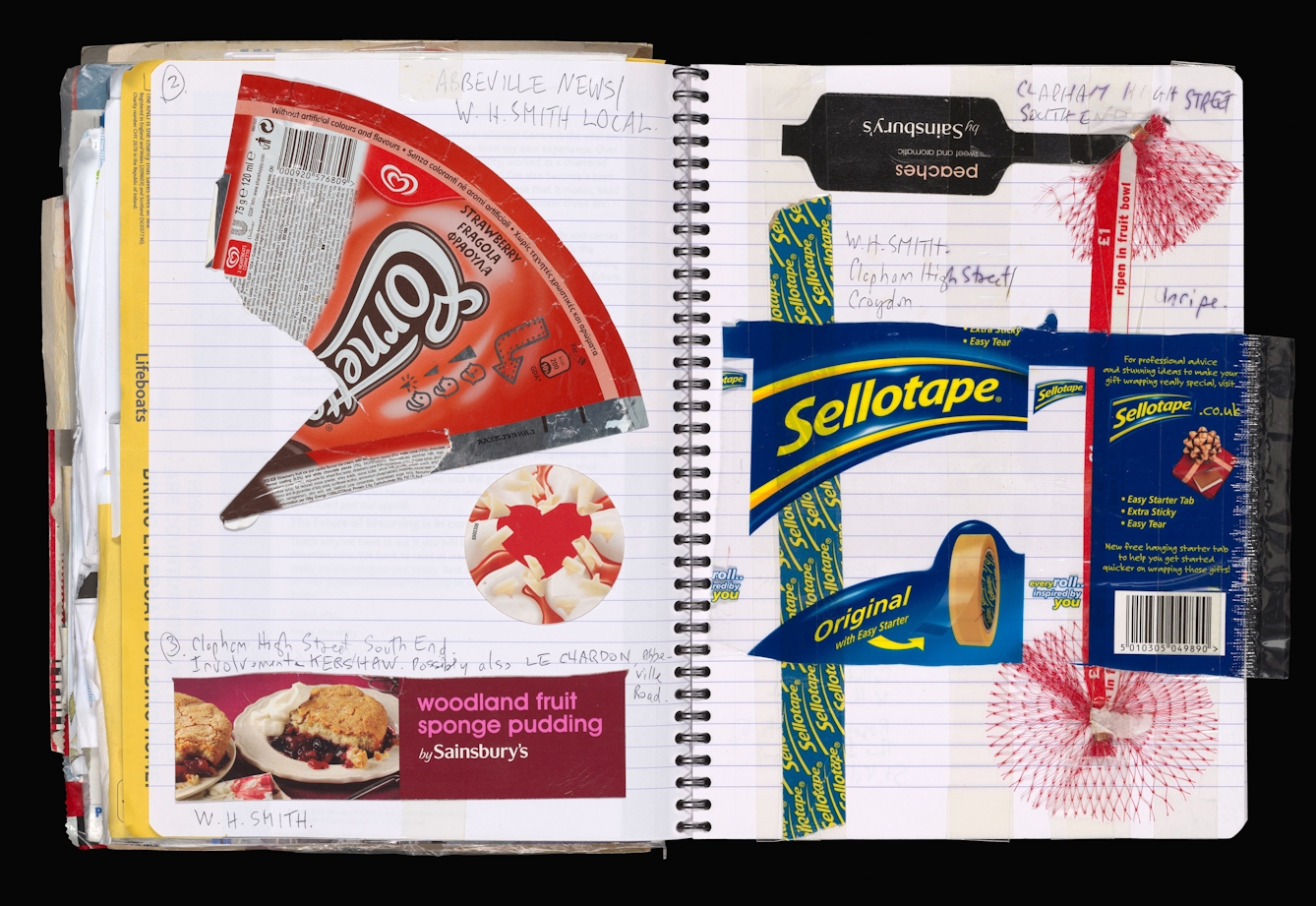

On a summer’s day in 2013, a woman called Audrey Amiss died alone in her south London flat, aged 79. On that day, she had eaten a Cornetto ice cream and a Sainsbury’s fruit sponge pudding before sticking the packaging down into a lined notebook, a scrapbook where she documented all the food she ate and household items she used every day.

She sketched a few items she could see in her home. She wrote a letter to the charities Scope and Freedom from Torture. She tucked a bus ticket to Croydon and a receipt for a cheese sandwich into a log book, ready to be pasted down and annotated with her thoughts on the day’s activities. In her account book, she recorded, next to a receipt, that she’d “trudged the route. Arrived home exhausted. ZAPPED. CHEATING.”

After 10 July 2013, the rest of the pages of these volumes are blank, marking the final moments of Audrey’s life.

When Audrey’s niece and nephew, Kate and Steve, visited the flat soon after her death, it was the first time they’d stepped foot inside for many years. Audrey had lived with severe mental illness and spent periods of time in and out of psychiatric care.

In her later years, she’d preferred to be alone, and her family did their best to monitor and support her from a distance. Often their contact with Audrey would be via a call or letter from the local police station or hospital, informing them that Audrey was in their care.

PP/AMI/D/234: Scrapbook. The final pages of Audrey Amiss' last scrapbook. 2013.

Whether they saw Audrey or not often depended on her state of mind on the day of a planned visit; Audrey’s niece recalled arranging to visit, and being turned away at the door as Audrey told her she was too busy for visitors. And Audrey was busy – a busyness of endless recording, accounting, tallying and writing, seeking to find connections between objects and symbols and items she encountered, and driven by a compulsion to record her experiences.

Audrey documented all aspects of her life, from the moment she woke in the morning until she went to bed at night: sketching items and people around her, recording every letter she wrote and sent, pasting down cereal packets and sweet wrappers, and writing endlessly about her daily experiences.

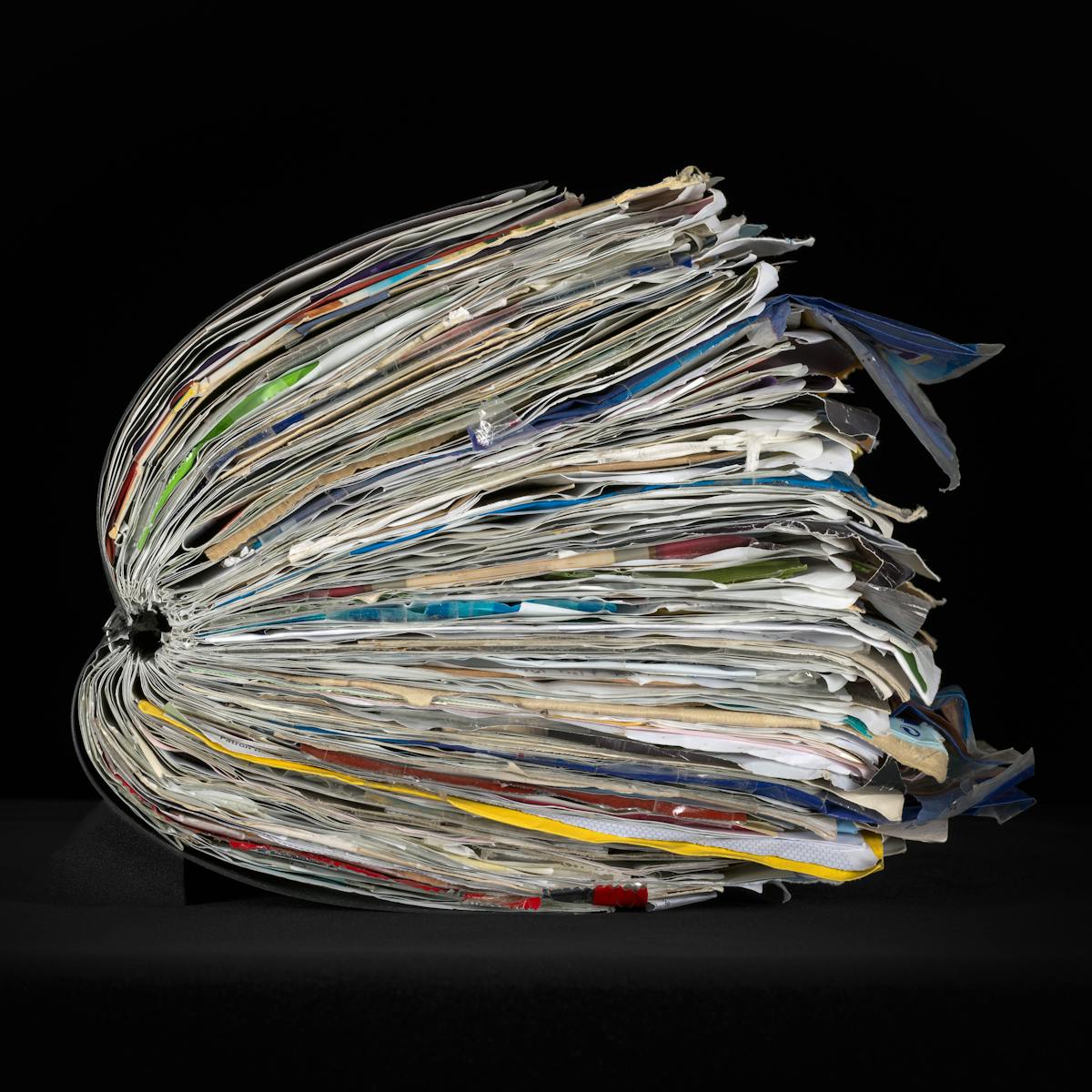

This busyness is conveyed in the number of volumes she filled: 854 sketchbooks, 234 scrapbooks and photo albums, 47 account books, 37 record books, and 16 log books. Through scribbled notes and annotations, annotated receipts and food packaging, detailed logs of letters written and sent every day, and meticulous accounts of her comings and goings, Audrey’s world is conveyed in streams of thought and bursts of activity.

Fragments of a life

As Kate and Steve walked into Audrey’s home, they found over a thousand volumes piled high and precariously, tucked behind doors among dust and leaves, and inside drawers, on unused beds, and up against skirting boards. They’d known that Audrey sketched and painted, but the sheer volume of material was staggering and overwhelming.

A pile of unread post waited by the front door. In the kitchen, above unused counters, coronation-era mugs were thick with dust and cobwebs. On the walls of the living room, paintings by Audrey hung framed and slightly askew. Above, the ceiling boards were bare, the plaster exposed from Audrey agitatedly banging to the upstairs neighbour with a broom handle. A copy of the Radio Times sat folded open on 10 July 2013.

Documentation photographs from a survey visit to Audrey Amiss' house in Clapham South, 2014.

In the spare room, two single beds were stacked with volumes of scrapbooks and photo albums, the wardrobe showing a few of Audrey’s colourful blouses. On the dressing table, volumes were splayed open from the weight of the junk mail and packaging pasted inside.

As the family started to sort through and read the scrapbooks, they realised just how extraordinary this material was. Here was the Auntie Audrey they’d known their whole life, but through the lens of her own writings and drawings, her intimate thoughts and her way of seeing the world were brought into the light.

Each type of volume had a clearly defined purpose and each was filled in on a mostly daily basis: scrapbooks contained food packaging, junk mail and other ephemera, annotated with her thoughts on how the food tasted and picking out aspects of the product design that caught her attention.

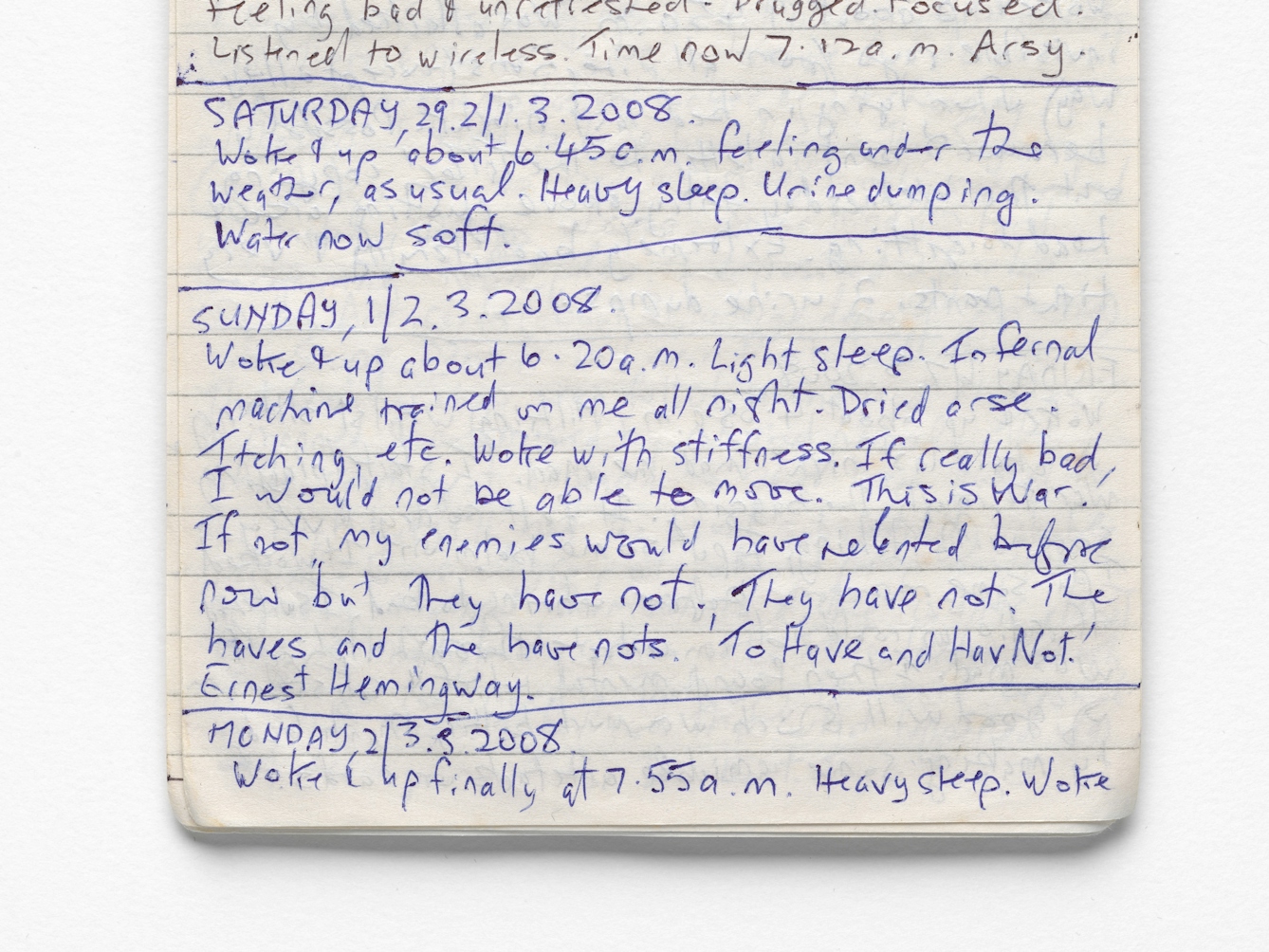

Account books documented every penny that Audrey spent, with receipts for purchases stuck down, and angry annotations about being wrongly charged or asked to leave shops for causing a scene. Log books recorded Audrey’s physical activities, down to her bowel movements, the time she woke up and what she listened to on the radio.

Through the lens of her own writings and drawings, her intimate thoughts and her way of seeing the world were brought into the light.

PP/AMI/G/5: Log Book. Entries for March 2008.

Record books contained a record of every letter Audrey wrote, who it was sent to and what the letter was about, with multiple letters sent each day to politicians, companies, celebrities, and other individuals.

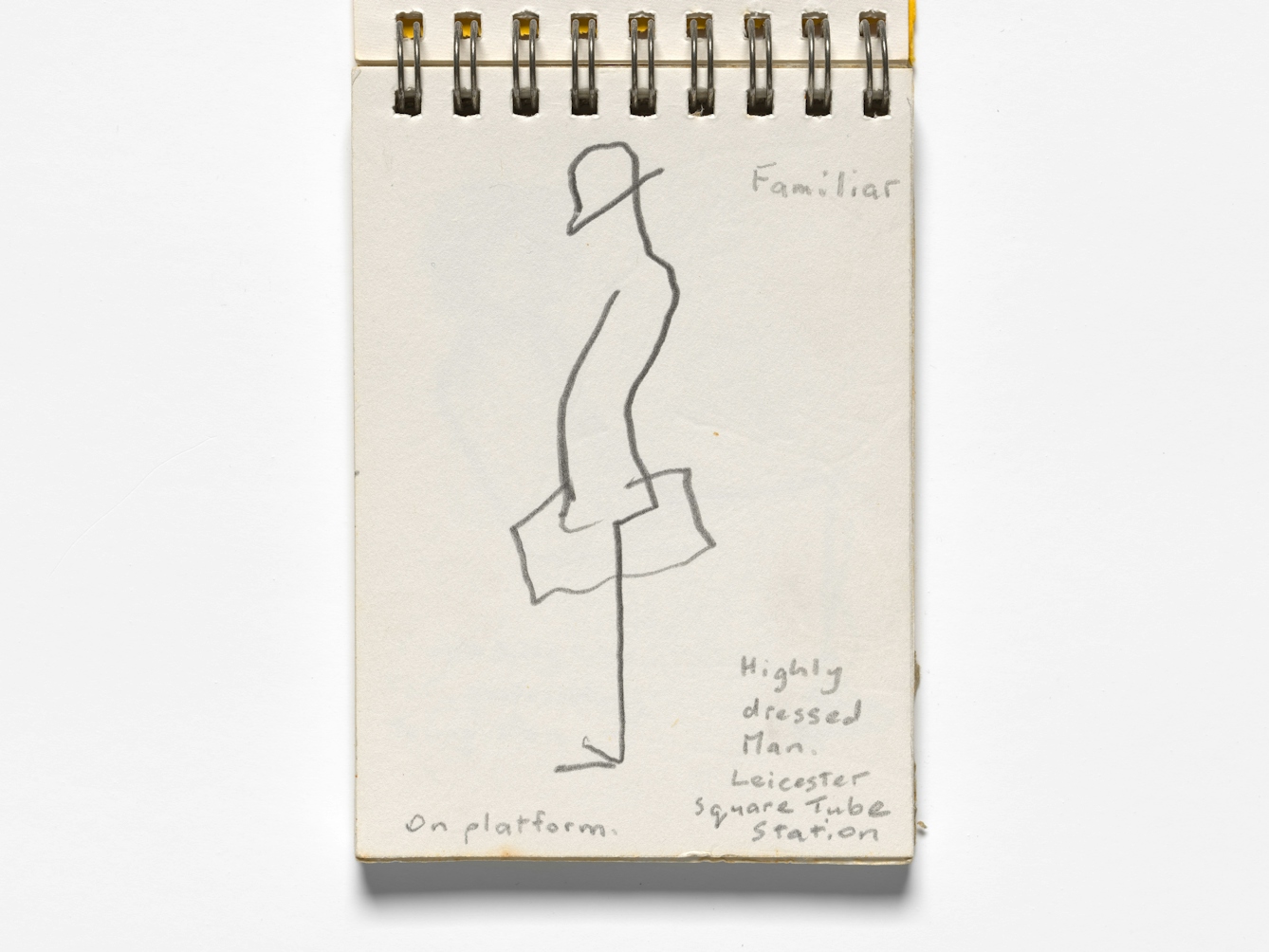

Sketchbooks contained drawings of people and objects Audrey encountered, at home or on trips around the local area, with entire volumes often completed hastily over the course of one day. Trips to the zoo were captured through one-line drawings of elephants walking, rhinos drinking, and children eating ice cream. Portfolios of early artworks from Audrey’s time studying at the Royal Academy sat alongside her later, more experimental canvas works and sketches, entered and often rejected from competitions and exhibitions.

Decades of Audrey’s life were recorded in minute and astonishing detail – fragments of a life lived, a puzzle waiting to be pieced together.

The family now had to decide what to do with all this material. It didn’t feel right that it should end up in a skip following a house clearance, but it was hard to get a measure of. They thought about what Audrey might have wanted to happen: had she left this material expecting someone to find and read it? What had she hoped might happen to her artwork after she died?

PP/AMI/B/104: Sketchbook. 'Highly dressed man. Leicester Square Tube Station'.

They knew Audrey had always wanted to be known as an artist; her studies at the Royal Academy had been cut short by her first breakdown and she had struggled to establish herself within the art scene during her life.

Giving Audrey back her voice

A chat at the school gates with another parent led Kate and Steve to Wellcome Collection, wondering whether Wellcome might be interested in the stuff as an example of a person’s experiences of living with mental illness.

At Wellcome, we aim to challenge the way we think and feel about health, but archives are usually told from the perspective of those who have power. Archival records are dominated by the voices of white male doctors, and those with direct experiences of ill health are often absent or sidelined. Audrey’s collection offered the opportunity to redress that imbalance, by placing her story in her own words front and centre.

Faced with such unique and complex material, we considered whether Wellcome was the best home for it, if it was even possible to preserve a collection full of diverse and degrading packaging and plastics, and what our ethical responsibilities as archivists were. We questioned whether acquiring the archive meant that Audrey would be pigeonholed as a mental health patient, as an example of “lived experience”, and whether her work would be seen as “outsider art” rather than assessed on its own artistic merit.

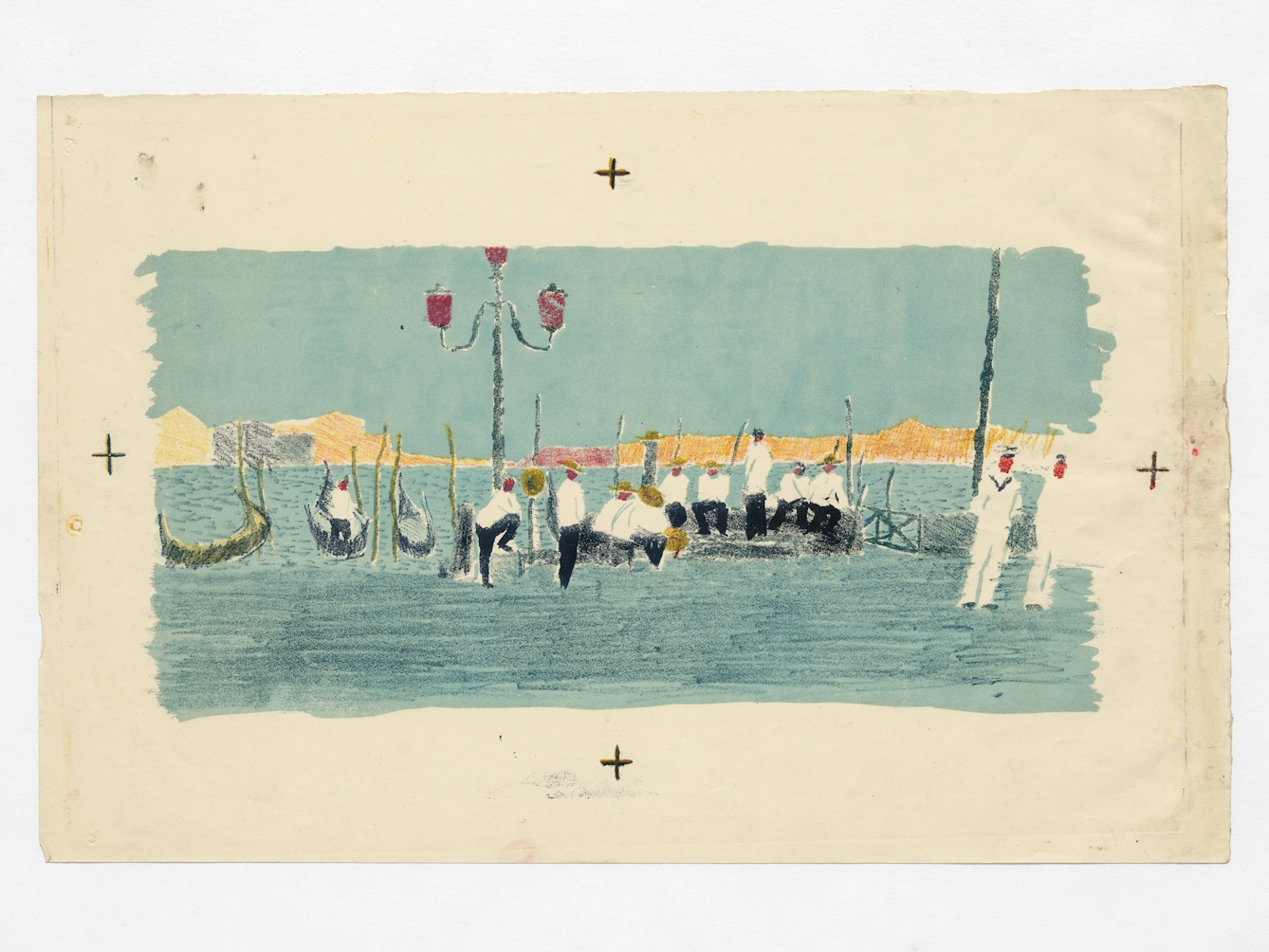

PP/AMI/C/1/20: Gondoliers on water (this title has been supplied by the cataloguer for identification purposes).

We considered whether it was possible to take the collection in its entirety, which needed enormous conservation intervention before it could even be made available. We recognised the huge responsibilities, and the need to ensure that we framed it in a way that gave Audrey her voice and autonomy back.

As we considered these questions, we realised the biggest one – what Audrey would have wanted – was something that would always remain unknowable to us. Yet still it felt there was something about Audrey pulling us in – a desire to work through the difficult ethical questions and find a way to give Audrey her own voice back through the catalogue.

When I first encountered one of Audrey’s scrapbooks, I didn’t realise just how intimately I would get to know her, and how I would spend days lost down rabbit holes as I tried to understand her way of thinking and seeing the world in order to catalogue the collection.

Over the coming years, I was going to develop an intimate and challenging relationship with Audrey, never having met her, but getting to know her through the material she left behind.

You can explore the Audrey Amiss archive(view in catalogue) through our online catalogue. To see the archive, you need to join our library and request to view specific items from the collection.

About the author

Elena Carter

Elena Carter focuses on developing the collections at Wellcome to challenge the way that we think and feel about health. Elena is particularly interested in radical and social histories and material that gives voice to marginalised groups. As Collections Development Archivist, she works directly with people to find the best home for their materials, with a focus on working collaboratively and ethically.