A manual of elementary chemistry : theoretical and practical / by George Fownes.

- George Fownes

- Date:

- 1869

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A manual of elementary chemistry : theoretical and practical / by George Fownes. Source: Wellcome Collection.

37/882 (page 33)

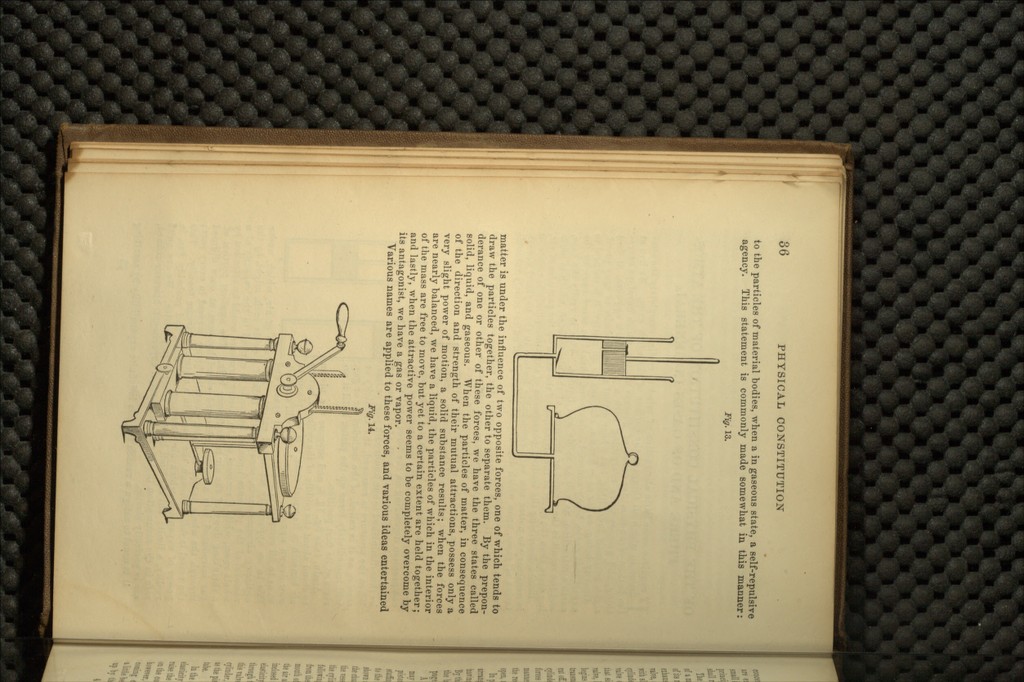

![gravity of liquids; the one that floats indifferently beneath the surface, without either sinking or rising, has of course the same specific gravity as the liquid itself; this is pointed out by the number marked upon the bead. The hydrometer (fig. 9) in general use consists of a floating vessel of thin metal or glass, having a weight beneath to maintain it in an upright position, an€ a stem above bearing a divided scale. The use of the instru- ment is very simple. The liquid to be tried is put into a small narrow jar, and the instrument floated in it. It is obvious that the denser the liquid, the higher will the hydrometer float, because a smaller displacement of liquid will counterbalance its weight. For the same reason, in a liquid of less density, it sinks deeper. The hydrometer comes to rest almost im- mediately, and then the mark on the stem at the fluid-level may be read off. Very extensive use is made of instruments of this kind in the arts; they sometimes bear different names, according to the kind of liquid for which they are intended; but the principle is the same in all. The graduation is very commonly arbitrary, two or three different scales being unfortu- nately used. These may be sometimes reduced, however, to the true num- bers expressing the specific gravity by the aid of tables of comparison drawn up for the purpose. (See APPENDIX.) Tables are likewise used to reduce the readings of the hydrometer at any temperature to those of the normal temperature. The division of the instrument from below, upward, into 100 parts, is much to be preferred to these arbitrary scales. Half of these divisions must be made upon the stem. The 100th division indicates the point of immer- sion in distilled water at 15-5° C. (60° Fahr.) If in another liquid the instrument sinks less deeply, for example to 60, then 60 volumes of this liquid weigh as much as 100 volumes of water. Hence the weight of 100 volumes, that is, the specific gravity, is 1^0Tp = l-67. By this arrangement of the scale, it is evident that the reduction of the specific gravity is so simple that no tables are required. A very convenient and useful instrument in the shape of a small hydro- meter, for taking the specific gravity of urine, has been put into the hands of the physician ;* it may be packed into a pocket-case, with a little jar and a thermometer, and is always ready for use.f Fig. 10. [* Tho graduation of the urinomcter is such that each degree represents 1-1000, thus giving tho actual specific gravity without calculation, for the number of degrees on tho scale cut by the surface of the liquid when this instrument is at rest, added to 1000, will represent the den- sity of the liquid. If, for example, the surface of the liquid coincide with 18 on t specific gravity will be 1013, about the average density of healthy urine. — R. B.] sity of the liquid. If, for example, the surface of the liquid coincide with 18 on the scale, tho pecific gravity will be 1013, about the average density of healthy urine. — R. B.] [f The mode of determining the specific gravity of a liquid by means of a solid has been omitted](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21183958_0037.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)